Issue 7: Feeling

What Vibrates Within Us

Every artist has a bit of a waste collector in them. I’m fascinated by abandonment and for many years have been picking up obsolete electronic objects before they reach their final destination. I now have a collection of the most varied types and I am interested in transforming them into new electronic objects. The french philosopher Catherine Malabou said construction is counterbalanced by a form of destruction, and creation can only occur at the price of a destructive counterpart. From 2013 on, my creative process has included this reuse of technology. I do not design artificial intelligence machines, but rather, what I call, sensory intelligence instruments. I invite users to experience and interact with simulations and synesthetic sculptures and installations.

When I disassemble an electronic object, I catalog the different mechanisms and familiarize myself with the motors and their vibrating systems. A vibration signal has three qualities: displacement, speed and acceleration, and they are all inextricably linked. According to Human Response to Vibration (2005) by Neil J. Mansfield:

Vibration is a mechanical movement that oscillates about a fixed (often a reference) point. It is a form of mechanical wave and, like all waves, it transfers energy but not matter. Vibration needs a mechanical structure through which to travel. This structure might be part of a machine, vehicle, tool, or even a person, but if a mechanical coupling is lost, then the vibration will no longer propagate.

Mansfield, 2005, 2.

For the propagation of movement, it is necessary for an electric motor to be encapsulated. The engine body must be enclosed to keep it still and allow the rotation only of its head. When I create a new piece, I change the original state of the components, so they behave differently. This transformation is a way of hacking the system. These works developed into my research, Vibratory Body: When movement calls for pause. Despite the ambiguity in the phrase the movement calls for pause, I do not mean displacement. I am referring to the need to pause our thinking and take time to perceive new forms of interaction and the sensitivity of our body.

The principle of Vibration

A principle is an assumption that serves as a philosophical basis and supports a fundamental thought. The principle of this work—that is, the beginning, the embryo—is a research process in visual poetics. Vibration, on the other hand, touches concrete materialities. It is an element that moves the material and is moved through different substances. Therefore, the principle of vibration, in this instance, was the encounter with what would become my greatest research tool: the vibratory component.

Many times I have been asked about the sexual character of vibration. Vibrating sensations surround us in ways that reach beyond the more common examples of phones and sex toys. We live immersed in vibratory signals. I dedicate myself to vibration as a principle of pleasure in relation to the whole body.

I found Shelley Trower’s Senses of Vibration: A History of the Pleasure and Pain of Sound (2012) illuminating, as a source to outline the possible relationships between body and vibration. In addition to the scientific context of the past two centuries, vibration is perceived as something natural and machine-like, which, as the title says, can lead to both pleasure and pain. Pain, according to Trower, would be located in excessive experiences of vibrating machines, as in transportation and other technologies. Pleasure, on the other hand, can be seen as moments when an amplified and harmonized vibration is sought, making it a “good vibration”.

Trower highlights that the anxiety generated through the permeabilities of the body is something that the excessive use of technologies has caused. Intense and direct relationships, even if physically distant, create new forms of relating to others and objects, because it gives a new meaning to the fixed borders of the body:

In this scenario, the distinction between object and subject, or between world and self, again totally collapses. Objects in the external world vibrate the sensitive self, the very sensitivity of whom in the form of vibrations radiates outwards, as the sound of an instrument, to become part of that world. There is a two-way process, in other words, whereby external vibrations seem to set the matter of the body into a kind of sympathetic vibration; vibrations in the body then radiate outwards into the world beyond, in turn potentially vibrating another sensitive person

Trower, 2012, 11.

The works presented in this publication require an active body in order for it to function, since the trigger is initiated by the interaction of the user. In this way, the vibrating objects that I create are an invitation to reconnect with our own bodies. In introspective moments, the vibration became a foundation for my artistic interventions, and I was the first to interact with my inventions. However, I created this experiment to experience it myself and then share it with others.

Utopian rotations and the machine Becoming

As part of her research, Trower (2012) studied the relationship between women and vibrating machines such as sewing machines, trains and bicycles. She describes the different contexts of various activities in a dichotomous way for the treatment of hysteria, or, prohibited, for bringing states of excitement to the female body.

In the beginning, objects of desire were used as therapeutic articulations. At the moment, their use is in the service of sexual health or aesthetic events. If we interpret the theory of Object A, explained by Lacan in Seminar X (1962-63), in the sexual act when the vibrator enters an experience, the machine becomes the person and the pleasure becomes the machine, interchanging its states of principle and invading the boundaries of the body. Vibrating sculptures that evoke sensory experiences can also be invasive. But how can someone question another body without invading it?

Sketch of “Inside Voice” (2018) showing a person talking to a microphone in front of someone sitting on a chair with a speaker attached to the back.

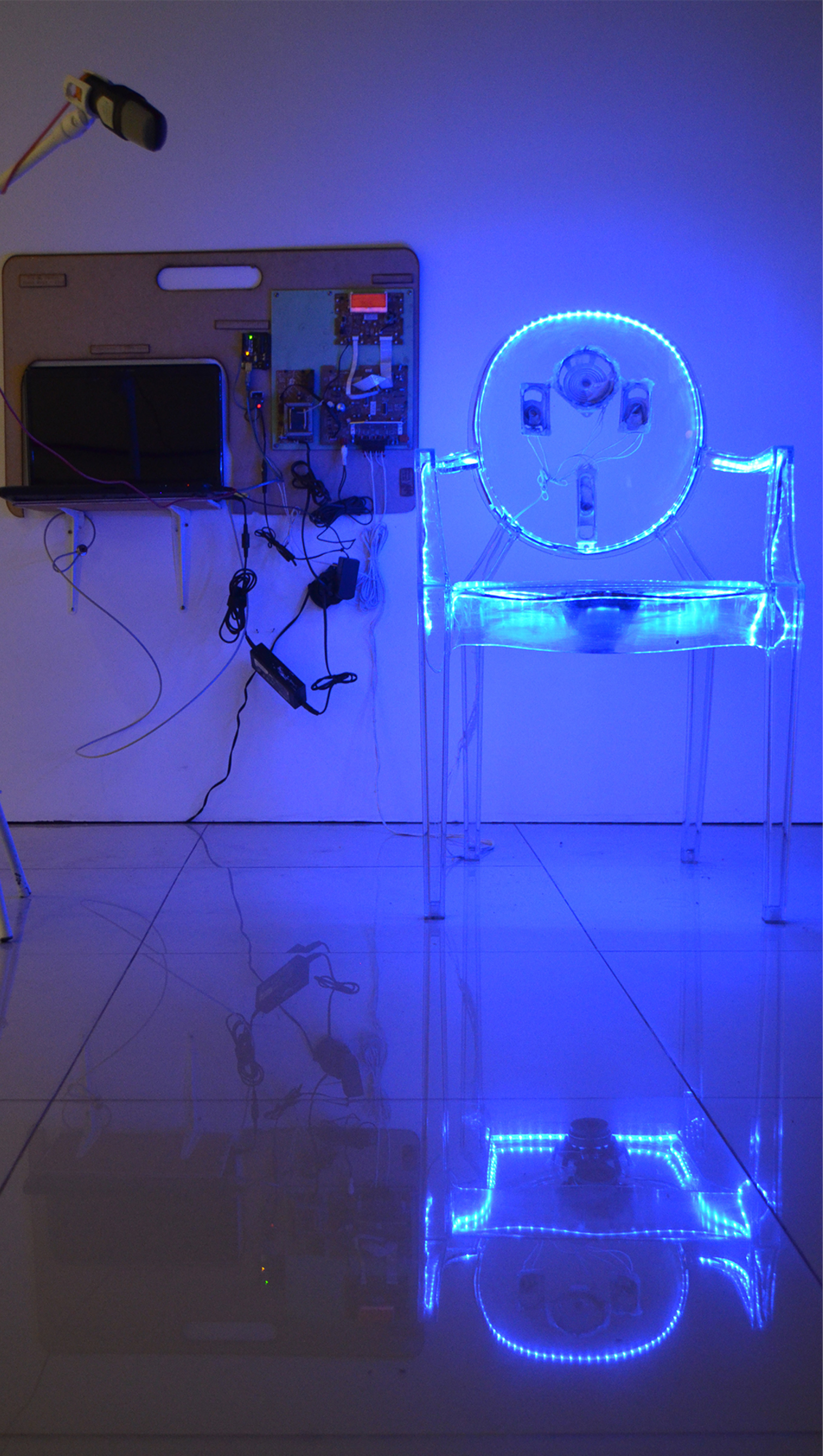

In my recent work, I created tactile experiences with sound through seatable devices or installations. I found it curious how, when vibration is connected to the lower body, it initiates discussions about sexuality. In Inside Voice (2018) my aim was to bring body, mind and voice closer to each other. This work is an interactive piece composed with a microphone and a transparent acrylic chair surrounded by a blue LED strip. On the seat and back support of the chair, I attached six speakers without the paper cones. Among the objects, I included a panel with a series of wires and electronic elements that performed the transcoding of the microphone and transmitted it to the chair.

To increase the vibration, the speaker cones were removed and two refurbished amplifiers were inserted between the input (microphone) and the output (chair). In addition to these, the piece featured a computer running a PureData program, which made the sound slower and lowered its pitch. Thus, the highs were eliminated and with them, the ability to recognize the spoken words.

Photo of “Inside Voice” (2018) displaying a microphone next to a transparent acrylic chair lit up in blue. In the back, there is a panel on a wall holding a computer and a set of wires and electronics. (Photo: Carina Macedo)

In Words to Be Born to Psychoanalytic Listening in Maternity (1997), Myriam Szejer proposes that in utero, before there is a functional auditory system, the fetus is able to recognize and discriminate acoustic vibrations reflected by the amniotic fluid. In a way, this is listening through the skin (SZEJER, 1997, 80). My work falls within the concept of transposing the primarily uterine vibratory reaction. What vibrates, is an invitation to listen through the skin, a tangible and voluntary compensation for new discoveries through sensitive surfaces.

The presence of the Other

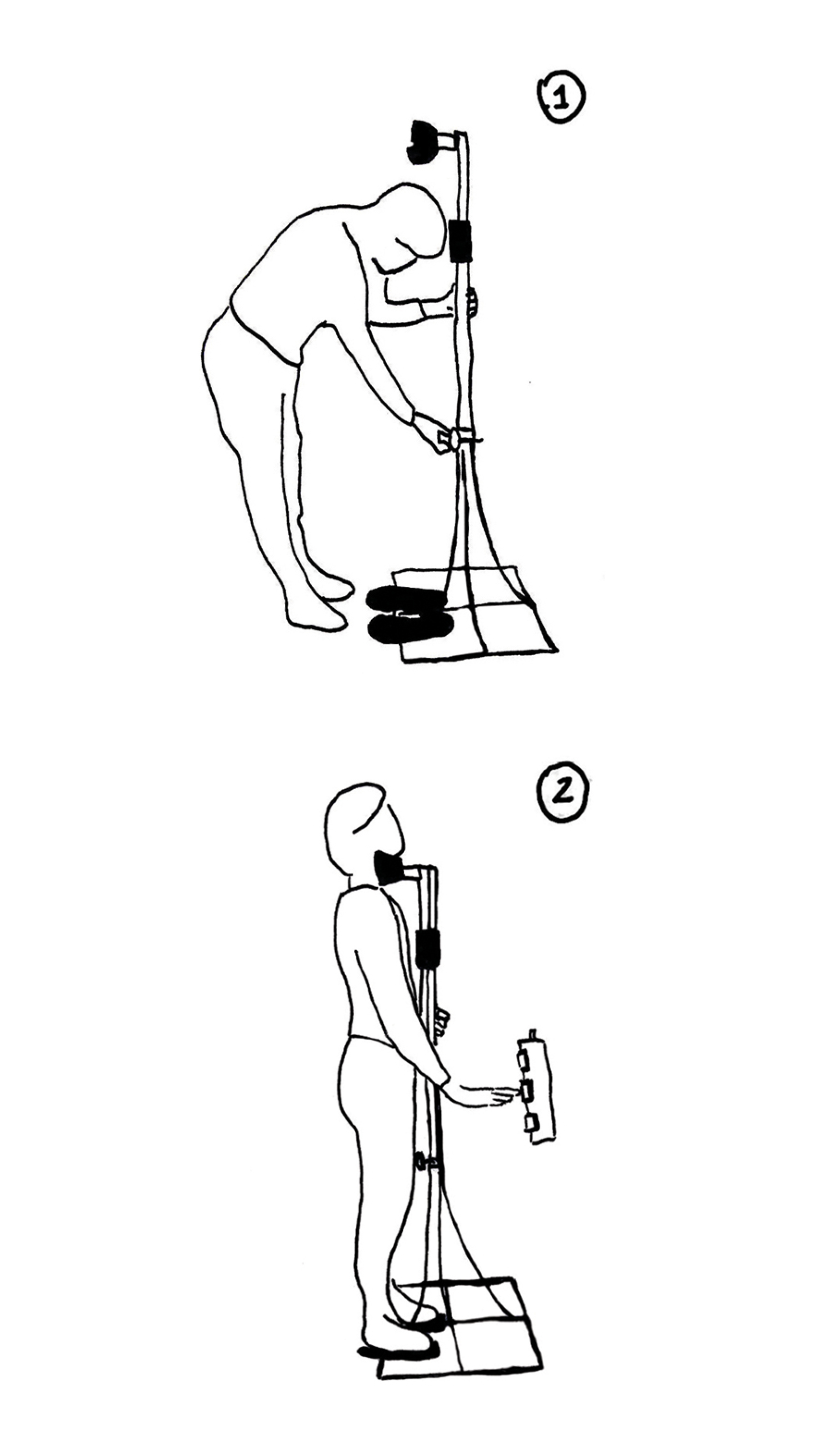

Sketch of “Anguish Massager” (2016) showing the user adjusting the height of the neck piece, and then embracing the sculpture and hitting the button.

My piece, Anguish Massager (2016) invites the audience to press a button and take the sculpture in a full body embrace. The three buttons are: digest (intense vibrations), forget (smooth vibrations) and reduce (light vibrations). In this work, the user might have a tactile experience with their whole body, a resignification of the boundaries of touch and a metaphor for massaging the person’s feelings. It is possible that feelings might be amplified, and not massaged, as a result of the mixture of pleasure and pain. Lacan defines anguish not as an emotion or feeling, but an affection, of the order of disturbance. An affection that does not deceive, is undoubted, and guides possible dissolutions of thought.

The user’s experience is directed by my putting constraints on how the piece should be interacted with, for example, specific parts of the body, even with a height adjuster for neck fitting. The pieces are programmed for particular actions. However, there is no closed interpretation to these experiences. Massaging anguish can offer either a good or a bad feeling. Here, the machine involves the person when it is in contact in a tactile, visual or audible manner.

Milton Sogabe (2010), a Brazilian artist and researcher, says that the audience member is no longer considered just a visual, thinking or listening being, but rather as someone that has a body with a complex sensory system that perceives the environment according to its memory and culture.

Photo of “Anguish Massager” (2016) showing a detail of the neck piece and buttons.

When I set out to make three-dimensional and interactive installations or objects, I ask myself: who is the object for? Although we do not always have a precise idea of the audience at a given exhibition site, my works are made in an attempt to raise awareness of an other. With this enigma, my desire is to take the works to the moment of exhibition, so that the interaction takes place and the user can explore and, actually, become the experiment.

Vibratory and sensitive body

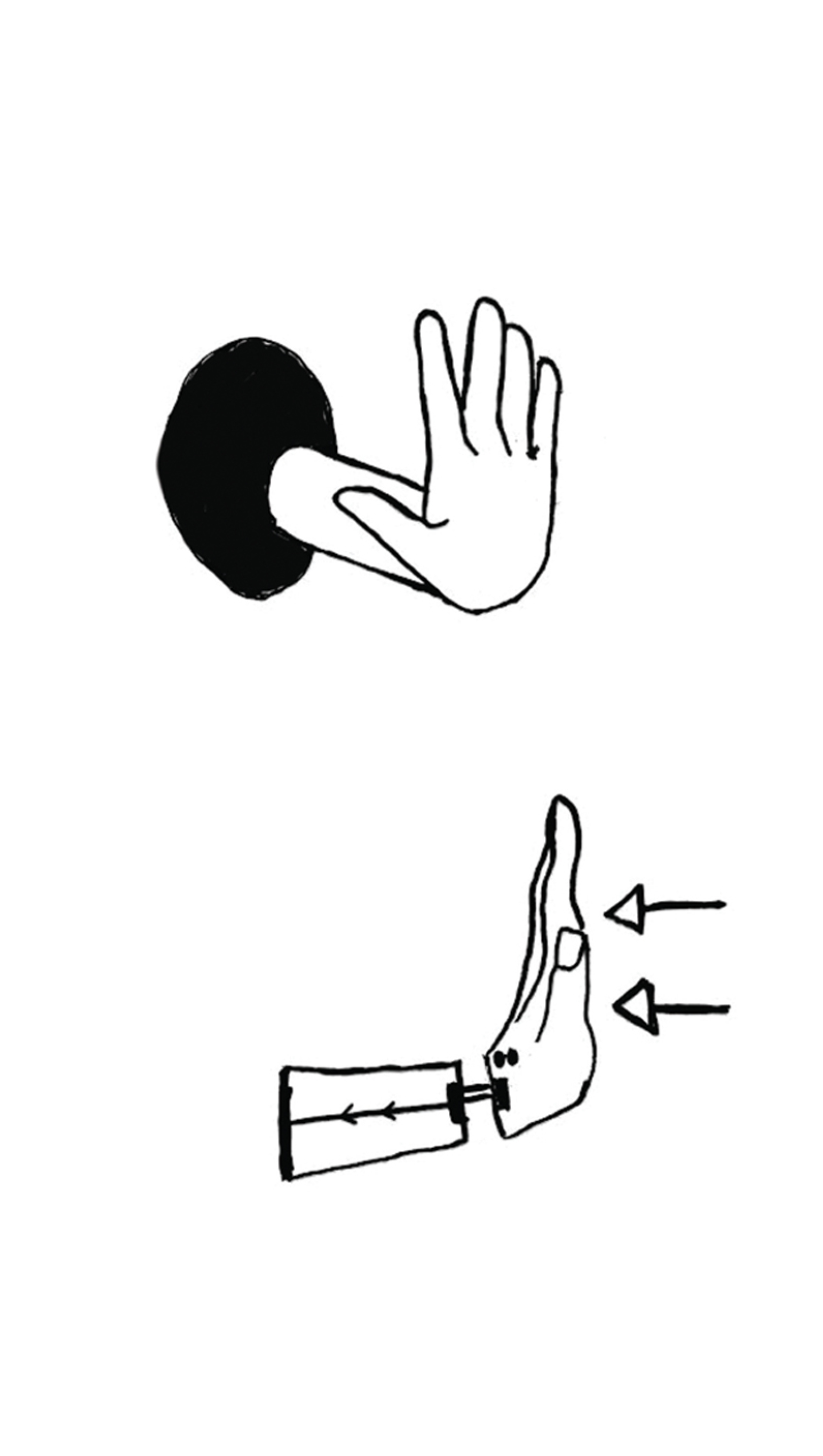

Sketch of “Sensitive Technological” (2018) showing detail of the resin hand with the orange squeezer spring and vibrating motors.

Throughout the creation of the work Inside Voice (2018) described above, I drew several possibilities of tactile objects that made the hand vibrate. The last work presented in this research consists of a hand-shaped, transparent copy of my own body, made in crystal resin. In it were inserted two mini vibrating motor disks and an orange squeezer spring. Paraphrasing Merleau-Ponty, my body is among things, trapped in the fabric of the world, made of the very same stuff (MERLEAU-PONTY, 1985).

My transparent and vibratory hand is called Sensitive Technological (2018). The user is invited to push their palm against the hand, which compresses the spring and makes vibrations spread. The perceptions of the work differed. Some people felt itchy, others felt as if they were connecting on another level with their cell phones. There were also negative reports, as some people were disturbed, because in the near future, they reflected, synthetic bodies would touch our organic bodies.

Mansfield (2005) describes vibration transmitted by a hand or arm as something that occurs whenever an individual holds a tool or a vibrating object. It’s part of an industrial phenomenon. And the size of the contact area influences the perception of vibration. In addition to bringing the characteristics of touch as a sensory path that is interpreted through texture, shape, temperature, size, movement and pain, the author highlights an important factor in this research: there is no way to predict the sensitivity of each person.

In such a manner, the Sensitive Technological‘s attempt is to generate strangeness because it is a familiar organic hand transformed into a machine, translucent and vibrating. José Gil (1997) exemplifies the body as a support for the inscription of psychic contents when commenting on the anthropological idea of the liberation of the hand. If the body can be seen as an instrument of the human being, the hand will be the main tool for the development of techniques that actually dates back to prehistory and up to the present day.

Photo of “Sensitive Technological” (2018) showing the transparent hand-shaped piece on the left, and a human hand interacting with it on the right. (Photo: Rodrigo Bello Marroni)

I offer, then, my greatest engine to the other: the mechanism that produced the vibrating objects with the fingers that triggered each key of this research. I afford my own image with its fingerprints, or rather a version of my body, transformed into a machine metamorphosed into vibration.

Final notes

The three artworks presented in this short version of my research are cited to invite the readers to think with me, to imagine their bodies as the protagonists of an experiment of touch, sensitizing their skin along with their minds. When talking about tactile artworks, the writing form limits the discussion to descriptions. Obviously, they are a poor substitute. Nothing can replace the an immersive physical experience.

I hope to keep investigating, in a collective form, what vibrates within us and which parts of the fast-paced daily life can actually equalize us. The works and thoughts described in this publication are experiments, today and always, that live on a constant trajectory.

Footnotes

FREUD, S. Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XII, 1914.

GIL, José, Metamorfoses do corpo Lisboa: Relígio D’água Editores, 1997.

LACAN, J. (1962-63), Anxiety: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book X Edited by Jacques-Alain Miler.

MANSFIELD, N.J., Human Response to Vibration CRC Press, Boca Raton., 2005.

MALABOU, Catherine, Ontology of the Accident An Essay on Destructive Plasticity Translated by Carolyn Shread. Polity Press, Cambridge, 2012.

MERLEAU-PONTY, M L’Oeil Et L’Esprit GAllimard, 1985.

PRECIADO, Paul Beatriz, Manifesto Contrassexual São Paulo: n-1 edições, 2014.

POPPER, Frank, Art of Eletronic Age New York: Thames & Hudson, 1997.SZEJER, Myriam. Palavras para nascer: a escuta psicanalítica na maternidade. São Paulo: Editora Casa do Psicólogo, 199.

SOGABE, Milton, Instalações interativas mediadas pela tecnologia digital: análise e produção SCIArts. Metacampo, Itaú Cultural, 2010.

TROWER, Shelley, Senses of vibration: a history of pleasure and pain of sound SCIArts. UK: Continuum Publishing, 2012.

ZIZEK, Slavoj, How to Read Lacan New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.