Issue 4: Bodies and Borders

Embodying New Tech: Cyberfeminist Artists and Female Body Representation

This article attempts to visualize the ways in which cyberfeminist artists approached the problem of corporeality in the U.S. It traces a line through 1st and 2nd wave cyberfeminism and post-internet artists, using three artists indicative of each wave to see how the movement arose and evolved since the 1990s.

The body is a crucial site for feminist intervention in art practice. To control the visual reproduction of their bodies, to be able to expose the pre-existing coded representations that contributed to women’s oppression, was—and continues to be—a crucial step for women in the path to regaining active agency for themselves within society.

With the arrival of the web in the mid-80’s, feminists quickly realized its strategic potential: an instantaneous worldwide network for the circulation of ideas and images represented a new avenue for artistic production, providing both wide-ranging tactical visibility, as well as seemingly unlimited possibilities for political action. And thus, the cyberfeminist movement was created.

Continuing the fight feminists had started in the years that preceded them, cyberfeminist artists were adamant that women’s bodies stop being mere passive women objects exposed to the male gaze. Instead, they focused on becoming active wired political participants in full possession of their bodies and iconography.

How do cyberfeminist artists use their own body in art on the network to change the ways Western culture understands the representation of the female body and further the feminist cause? How does the involvement of new technologies within the feminist art practice benefit or hinder the relationship cyberfeminist artists and women in general have with their own bodies and their visual representation? How do cyberfeminist artists try to ‘speak corporeal’ (embody) in such a visual art practice? Are they successful? This article attempts to answer these questions, and to visualize by means of concrete examples the ways in which the problem of corporeality within new technologies and in particular net.art arose and evolved in the United States1.

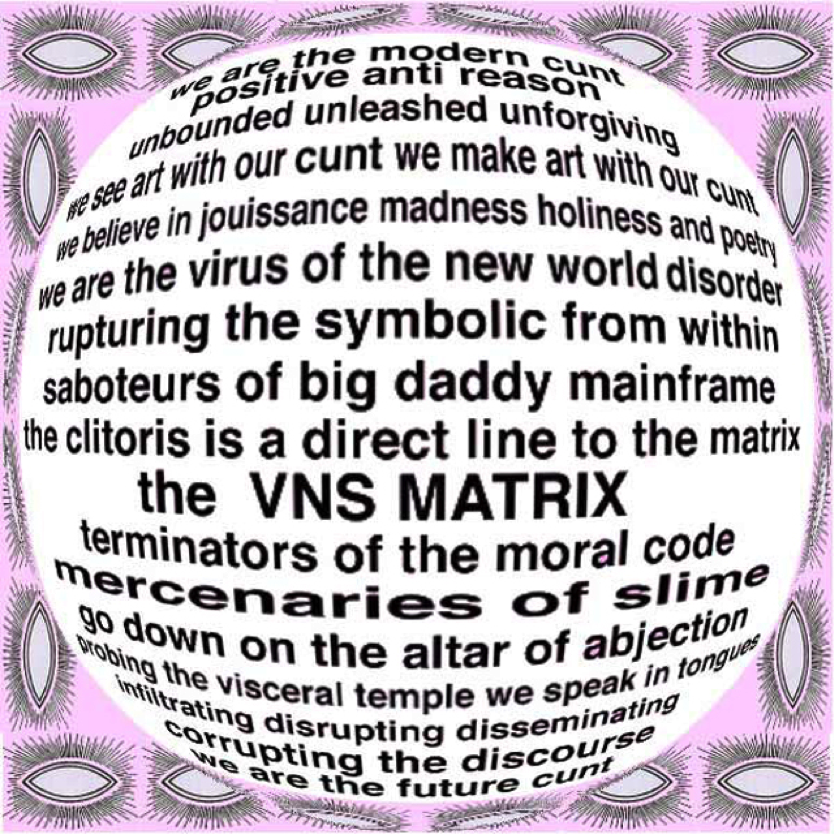

VNS Matrix, A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, 1991, Web image.

New Technologies And The Net: The Early Stages Of Cyberfeminism

Following the neo-conservative and neo-liberal policies put into place during the Reagan presidency (1981-1989), the feminist Sex Wars and the emergence of the AIDS epidemic which resulted in a call for social purity, a resurgence of sexual repression, and even a rise of racist rhetoric, the 1990s visual culture returned with a vengeance to the body.

The term cyberfeminism was simultaneously coined by Sadie Plant and the VNS Matrix collective in 19912. Plant’s position on cyberfeminism was one of disruption. There was power in using the term “disruption3” at such a time, especially for the feminist movement which preoccupied itself with the coding and decoding of visual culture and language as part of its efforts to create a new corporeal language that spoke for and to women. The term also embraced the potential that the new technologies had to re-calibrate the system, both in the technological and also in the social, cultural and political spheres. Whether as a source for material or as a medium for expression, the net’s individualistic style of activism allowed cyberfeminists to escape domination by the institutional authority whose patriarchal system of values second-wave feminists had tried to undermine with limited success.

Technology: Claiming Cyberspace As a Female Territory

The initial wave of cyberfeminist art focused on the relation between women and machines and the techno-utopian celebration of a cyborg consciousness.

To speak of the corporeal at the beginnings of cyberfeminism required an actualization of the limits of the body beyond just the skin. The clone and cyborg women constituted a new era: they were no longer to be passive women objects. Well-equipped to integrate new subjectivities in cyberspace, cyborgs would supposedly allow for a rewriting of the female body’s status within society. As cultural theorist William Mitchell noted in 1995: “ ‘Inhabitation’ will take on a new meaning—one that has less to do with parking our bones in architecturally defined spaces and more with connecting your nervous system to nearby electronic organs4.” Influenced by Donna Haraway’s much acclaimed “Cyborg Manifesto,” much of the first part of the 1990s was concerned with gendering the new technologies as feminine. VNS Matrix’s Cyberfeminist Manifesto of the 21st Century and Lynn Hershman Leeson’s project The Dollie Clones exemplify many of these theoretical ideas in practical terms.

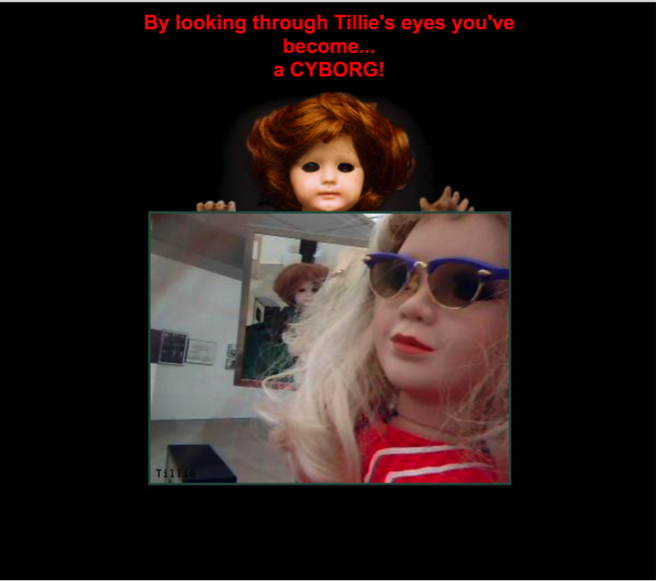

Lynn Hershman Leeson, three screen shots from “Tillie the Telerobotic Doll”’s website at different times, from the Dollie Clone series, 1995-98, Web Images.

In The Dollie Clones series, Hershman Leeson creates two cyborg dolls—Tillie and CybeRoberta—as an extension of her body. What makes the dolls cyborgs is not that they are made of man-made materials. Rather, they are cyborgs because their eyes have been replaced by cameras, extending Hershman Leeson’s vision beyond what her body can see. The museum visitor can also see what the doll Tillie sees on a screen monitor positioned at her feet. However, her right eye is connected to the internet. She sees in a 320×200 grayscale, and is refreshed every 60 seconds. Roberta has only one cyborg eye that performs both functions5. These “Eye-cons” allow viewers to move the doll physically and telerobotically. Viewers literally use the doll’s eyes as a vehicle for their own remote and extended vision. By their action, the viewers themselves are turned into cyborgs, beings whose virtual reach and in this case, sight, extend beyond physical location. Thus Tillie and CybeRoberta are not only the extension of Lynn Hershman Leeson’s body, but the extension of internet users as well, since it is the internet users’ eyes that activate their cyborg consciousness. As such, claiming not only cyborg imagery but also its inherent qualities in the disembodied cyberspace becomes a political act in cyberfeminist art practices that allows for the rematerialization of the female body in cyberspace.

View of The Dollie Clones installation, 2016, courtesy of Lehmbruck Museum.

Projects such as Hershman Leeson’s had the potential to create horizontal, nonhierarchical systems that demand a response to the issues at hand. Not only did interactive cyberfeminist art practices empower viewers through unconventional non-linear structures, autonomous action and gendered agency, but they also challenged pre-existing representations of the female body and the patriarchal gender stereotypes that accompany it.

However, although at first cyberspace seemed to be an egalitarian tabula rasa—unhampered by physical bodies and void of informational cues about gender, age, and class- the images and the meaning of bodies that were portrayed in it showed that the internet was not such an innocent place after all. Persistent stereotypes and cyber pornographic content forced second wave and post-internet cyberfeminists to re-route their efforts into subverting such stereotypes from within through humor and parody, hiding their militancy as a Trojan Horse would a Greek or a virus6.

Cyberfeminism 2.0: Reversing the Terms of Dominance and Subordination Accompanying the Female Body on the Net

The project of second-wave cyberfeminist Preema Murthy exemplified these concerns and allowed internet viewers to visualize the issues that arose when the physical body in an intimate environment collided with the public terrain of cyberspace.

Bindi Girl, intertwined issues of gender and race with new technologies—and in particular the webcam7. Murthy’s project offers the perfect sexual fantasy of the ‘mysterious’ oriental woman, playing on these stereotyped expectations to better undermine them in the end. The site starts with a warning that all viewers must be over the age of 21 as the content is explicit8. However the spectator soon realizes all options in Murthy’s camgirl site subvert their conventional functions from the very start. For instance, while the warning sign mimics pornographic camgirl sites, it is unnecessary as there is no nude content; the flash sequence of seductive images of Murthy loops too fast to instigate the spectator’s desire so they cannot visualize or grab these images. By interrupting the visual pleasure of the internet user, Murthy parodies and counters the submissive efforts that her alter ego Bindi Girl performs as the ‘ideal’ Indian woman.

Preema Murthy, four screenshots of “Flashing Sequence”, from Bindi Girl, 1999, Web Image.

Murthy’s work also approaches issues of race that, while broadly discussed on the theoretical field of other disciplines, were not common in cyberfeminism. Part of the problem lay in the fact that many women of color and lower income had limited access to the net9. Preema Murthy was one of the few cyberfeminist artists with a POC background who worked on the commodification of racial markings and women’s bodies in cyberspace that resulted in white masculine domination of the net. Her work allows the reader to understand how bodies of ‘Others’ are approached in the hetero-normative system of Western culture and how those bodies are valued.

It is important to point out that in most of second-wave cyberfeminist projects, female spectatorship is never at the receiving end of the experiment. When female spectators do view such projects they are intended to analyze them as outsiders. Such militant modes of operation are limiting for women since—although they do offer alternatives for viewing their bodies—they are not offered a way to engage in the pleasure of being their own subject of desire. The next generation of cyberfeminist artists—the post-internet artists—instead tried to engage multiple types of audiences in different ways.

The Ambiguous Position of Post-Internet Cyberfeminist Artists: Exploiting Existing Social Contradictions From Within the System

If the earliest cyberartistic practices declared an interest in the relationship between the distinct spaces “online” and “in real life”, post-internet artists and cultural practitioners have most recently let go of this binary distinction and focused on the inverse: the blurred indistiction between the two10.

Although the term post-internet is still hard to define, generally speaking post-internet art differs from earlier net.art in that it does not focus on the novelty of the web as a tool to produce art, but addresses the ways in which it has altered the pre-existing social structures both in the digital space and the physical world11.

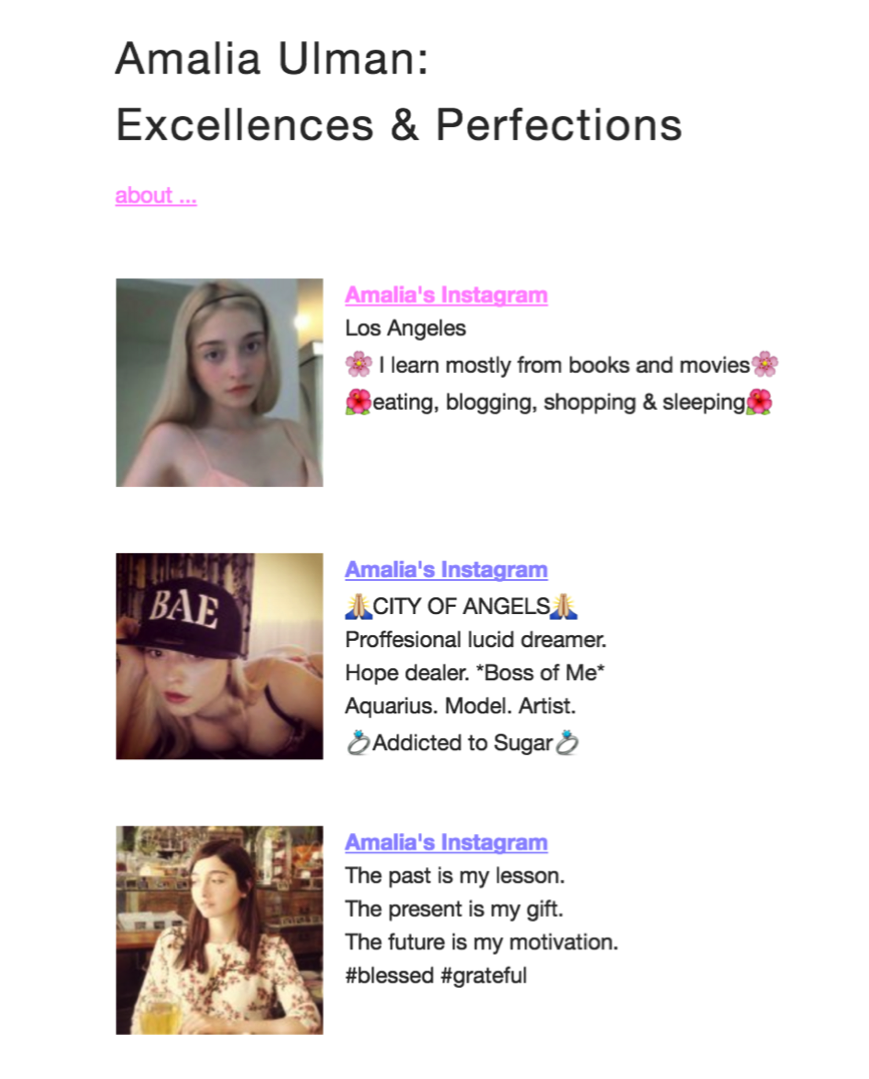

There is still an obvious distinction between the ‘virtual’ and the ‘real.’ However the intertwined nature of these experiences has come to define our daily life. Such varied experiences are clearly encountered in the work of post-internet artist Amalia Ulman. Between May and August 2014, Ulman conducted a scripted performance via her Instagram and Facebook profiles, uploading over 200 selfies. As part of her project Excellences and Perfections, Ulman underwent an extreme fictional makeover, transforming herself into an amalgamation of three main social media female stereotypes: the “Tumblr girl,” the “sugar baby ghetto girl,” and the “girl next door“12. Through this performance, she repeated a lie for a month, creating a truth she was unable to dismantle13.

Seen through the lenses of Instagram or Facebook, Ulman’s performance does nothing but further the stereotypes of women that are found everywhere on the World Wide Web. However such platforms were always meant to be the first layer of the reading of the work. They are not the final product but part of the creating process. As Tate Modern’s senior curator of photography Simon Baker notes, Ulman’s cyber performance is meant to be seen in the context of an exhibit or a museum14. As such, Ulman uses another of cyberspace’s resources through Rhizome, an arts organization that commissions, exhibits online, preserves, and creates critical discussion around net art15. Through the organization’s social media archiving tool, Ulman is not only able to preserve the way her Instagram looked like when she finished the performance, but also frame her pictures within the context of art, in which the viewer informed of the performance nature of the piece. The change of placement equates to a change in spectatorship. However, the performance would not have worked if it had not gone viral. Therefore visitors see the images and comments in context of a social platform. Herein lies the power of Ulman’s performance: the observer is the one observed, caught in a trap through the representation of her body set as a stereotype.

Amalia Ulman, “the Tumblr girl, the sugar baby ghetto girl, and the girl next door”, screenshot, from Excellences & Perfections, 2014, Web Image, Courtesy of Rhizome.

Moving Forward

Amalia Ulman’s digital performance offers a great analysis on how the body’s place in cyberspace and in the real world embody different experiences as the context shifts between the two places. It explores whether viral visibility can only lead to a situation where, as Guy Debord put it in 1967, “all of humanity would become a form of representation; [where we] no longer exist as our selves, but instead decline from real experience to merely [appear] as performing phantasms16.”

While the post-internet feminists of the early 2010s recognized that their predecessors’ techno-utopian dream failed to meet the initial expectations of a post-society devoid of any discrimination, whether their attempt to work within the system is proving successful is still unanswered. Nevertheless, many cyberfeminist artists’ projects have had an impact on the way women represent themselves in new technologies. The question now is will this situation result, once again, in the baring of the corporeal in women’s representation of their bodies, similar to the semi-failure of the first wave of cyberfeminist’s ideals? Or is there a possibility that even accepting such phantasms, a female body speaking the corporeal may yet survive?

Bibliography

Archey, K. (2015) “Bodies in Space: Gender and Sexuality in Online Public Space,” in L. Cornell and E. Halter (coed.) Mass Effect: Art and the Internet in the 21st Century, Cambridge, MA : MIT Press.

Christensson, P. (2006) “Trojan Horse Definition”, TechTerms, Sharpened Productions, Web, 05 June 2016, http://techterms.com/definition/trojanhorse>

Connor, M. (2013), “What’s Post-Internet Got to do with Net Art?” Rhizome, Web, 5 Apr. 2016, <http://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/nov/01/postinternet/>

–– (2014) “First Look: Amalia Ulman – Excellences and Perfections”, Rizhome, Web, 20 May 2016, <http://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/oct/20/first-look-amalia-ulmanexcellences-perfections/>

Corbett, R. (2014) “How Amalia Ulman Became an Instagram Celebrity”, Vulture, Web, May 30 2016, <http://www.vulture.com/2014/12/how-amalia-ulman-became-an-instagram-celebrity.html>

Dietz, S. (1998) “Beyond Interface: net art and Art on the Net II”, Minneapolis : Walker Arts Center, Web, 4 Sept. 2015, <http://www.walkerart.org/gallery9/beyondinterface/>

Evans, C. (2014) “An Oral History of the First Cyberfeminists”, Motherboard, Web, 7 Oct. 2015.

Hershman, L. “CybeRoberta”, Media Art Net, Web, 18 Apr. 2016, <http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/cyberoberta/>

Hershman Leeson, L. “CybeRoberta”, Web, 16 May 2016, <http://lynnhershman.com/cyberoberta/>

–– “Tillie the Telerobotic Doll”, Web 16 May 2016, <http://www.lynnhershman.com/tillie/>

Kholeif, O. (ed.). (2016) Electronic SuperHighway: From Experiments in Art and Technology to Art After the Internet, London : Whitechapel Gallery.

Lacan, J. (1949) “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience” in E. Fink and B. Fink (ed.) (2006) Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English, New York : Norton.

Mitchell, W. (1995) City of Bits: Space, Place, and the Infobahn, Cambridge, MA : MIT Press.

Neuendorf, H. (2016) “Tate Modern Taps Instagram Sensation Amalia Ulman for Its Next Major Show”, Artnet News, Web, 26 Feb. 2016, <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/amalia-ulman-instagram-tate-modern-410375>

Rhizome, “What We Do”, Web, 1 June 2016, <http://rhizome.org/about/>

Wilding, F. (1998) “Where is Feminism in Cyberfeminism?” paradoxa, 2: 6-12.

—