Issue 5: Reality?

Be All You Can Virtually Be

Be All You Can Virtually Be

by luming hao

Illustrated by Gabriel Brasil and Sofía Suazo

In the future which will come first, the war or the war game? A look back at video games from this century’s first decade to see how the renegade spirit of new media gets co-opted into the institutional powers that be.

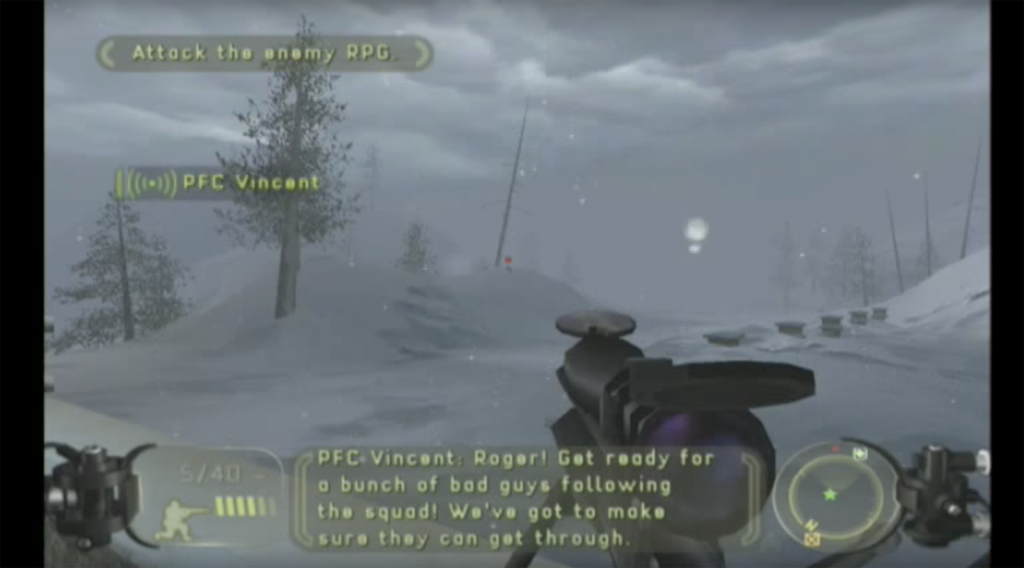

On the 4th of July, 2002, the US Army published their first video game. The result of a $6.3 million dollar in-house army-owned game studio, America’s Army was released as a free download(1). The game featured a few preliminary levels depicting different vignettes of the training experience: boot camp target practice, special operations exercises of patience, and medic training via scantron tests(2). The main gameplay revolved around a competitive multiplayer experience similar to Counter-Strike, where, despite random team assignments, the player’s team is always depicted as clean-shaven white and black men, and the opposing team is always depicted as bearded Arab avatars(3). Proudly and openly marketed as an innovation in the field of propaganda, America’s Army was an attempt to use cutting-edge gaming technology to let “the whole world to know how great the U.S. Army is”(4).

With every new exciting development in the lineage of media technologies, there is a tendency among cultural critics to believe that the bleeding edge of expression exists outside the bounds of institutional control. Even when these technologies are marketed as iconoclastic by the same hegemonic organizations, there can be dangerous optimism in possibilities of liberation. There is possibility for radically productive uses of nascent mediums, but unchecked faith can devolve into the unequivocal belief that they possess an inherently radical nature. By examining a recently gone era’s relationship with a genre of media that has now accumulated psychological distance from the present, we can be reminded of the ideologically dynamic nature of media technologies. To this end, we should examine the example of institutional uses of three-dimensional video games of the early 21st century for propaganda as a short study on the relationship between hegemonic organizations of control and vanguards of interactive entertainment media.

In the 1980s, Reagan predicted that video games could turn the masses into fight-ready militant citizens(5). This prediction was realized when, in 2008, a North Carolina man witnessed an accident involving a flipped SUV. He pulled two passengers out of the burning wreckage and controlled the bleeding of one using a towel as a makeshift dressing. The man claimed to have no prior medical training apart from playing the “medic” levels of the video game America’s Army(6). When America’s Army was released, the army’s traditional methods of recruitment cost around $15,000 per recruit, meaning only 400 additional recruitments could justify it’s astronomical $6.3 million budget(7).

The tradeoffs of digital worlds may be readily apparent, but their affordances make them irresistible to authoritarians of scale. As opposed to theater, film, music, and literature, video games require the full construction of a physical space in order to convey an area capable of exhaustive exploration(8). The results are often confined representations of the intended setting, but are capable of nearly infinite variations of perspective and scenario. Digital simulations promise an endless supply of cheap adaptations; live simulations require set design and a costume department(9).

Around the same time as the development of America’s Army, DARPA was tasked with evaluating possible uses for other off-the-shelf video game technologies. Motivated by the “varied,” “safe,”, “available,”, and “engaging” qualities associated with virtual training that physical trainings lacked. They began distributing copies of “DARWARS: Ambush!” internally, a modification of the recently released game Operation: Flashpoint(10). Operation: Flashpoint was a commercial video game already critically acclaimed for its depth of realistic detail and its accommodations to encourage a community of modders. This ease of modification is what attracted DARPA to adopt the game as the technological basis for their project, which later became the Virtual Battlespace series, now the official military simulation software for the US military as well as the militaries of Australia, Canada, Finland, France, NATO, New Zealand, The Netherlands, Singapore, and the UK(11).

Digital worlds are created with the inherent ability to modify themselves while time is locally frozen. The capacity for specification is limited only by the capabilities of the machine and the technical labor available. Frequently, this is mistaken as evidence for the feasibility of hyperrealism. When these efforts fall short, they can do so in ways that lay bare the beliefs, ambitions, and values of their creators much more so than the intended polished products ever could.

The public popularity of America’s Army inspired a subsequent project, the Virtual Army Experience, a set of touring trailers that traveled to festivals and fairs in lower middle class areas offering a 4D version of the heroic narrative found in the original (4D being the marketing term for movie chairs that move and vibrate along with the film). After waiting in long lines, entertained with pushup competitions and invitations to play Guitar Hero versions of Rage of Against the Machine (with the “I won’t do what you tell me” lyrics censored), patrons were briefed about a fictional Middle-Eastern conflict, then led into a room with an armed stationary Humvee. A film in front of the vehicle depicted a virtual jeep ride, where armed men take turns jumping into view and are seen dying seemingly from the marksmanship of the operators of the vehicle-mounted weapons. These theatrical deaths actually occur according to a predefined time sequence, not due to the “shooting” of the observers. The interactivity of the film was an illusion. If absolute realism were demanded, groups of teenage boys handling life-sized machine guns would not survive very long in even simulated combat. When the POV film ended, a veteran emerged to talk about their experiences and to give a toy to the youngest of the group(12). The Virtual Army Experience approached realism aesthetically, but had to compromise agency in order to instill a sense of inherent American power and superiority.

Destineer‘s Six Days in Fallujah took a different approach to the question of realism in simulated war. The project was inspired by Destineer‘s private contracting for the army: the Second Battle of Fallujah occurred while Destineer was consulting with marines of the 3rd Battalion, and a surviving marine suggested a video game could commemorate the pivotal yet devastating battle(13). Self-financed and inspired, Destineer set out to create the most realistic game they could in order to tell this narrative. They immediately began to create a custom game engine that, instead of the hollow geometrics traditional to most 3D software, would model the physical composition of every material object in the collection of city blocks that comprised the setting of the game. There was reasoning behind such a totalizing project of worldbuilding. Modern military tactics of war frequently rely on freely destroying the architecture and environment whenever a tactical advantage could result, and a fully modeled world would give players the freedom to use such tactics themselves. “Unfortunately, this decision inadvertently caused us to spend the first three years building an engine instead of a game… Everything falls out from this one decision to create a fully destructible game world, and I’m the one who pushed for it and authorized it, so it’s my fault,” said Destineer founder Peter Tamte(14). Destineer believed they could replicate the physicality and subsequent destruction of Iraqi architecture and Middle Eastern soil in software. And they failed.

The project was plagued with public criticisms and moral dilemmas, such as whether to visually model the virtual game characters after the real-life soldiers that were killed in the battle, codifying the ability for players to infinitely replay their deaths. During a segment on Fox News featuring Peter Tamte, infantry officer Read Omohundro and Tracy Miller, the mother of a fallen soldier, Omohundro explained that “This is not a memorial game. What it is is an interactive media format to actually educate the user and provide something for them to get just a fraction of an experience of what we did when we were there.” When asked to respond, Miller saud “Well, you know, it’s complicated. I think that as long as it’s a game, people who are playing it have some ability to control an outcome, and if they’re doing that, then it’s not going to be real.”(15). Two different publishers dropped support of the project before Destineer ultimately dropped it as well. Destineer released a small game based on the technology of Six Days in Fallujah, but to this day, the original project remains a victim of its aspirational realism.

However, hegemonic adoptions of new technologies do not always have to be well funded and coordinated efforts to build exemplary worlds from scratch. Repurposing existing products is more common, which was the practice of the gaming collective The Men of God International, which concentrated on establishing a missionary presence in five popular online games, one of which was America’s Army(16). According to their website, Men of God International was “an online community of men, women and children with one purpose and that is to win souls for Jesus through a unique and growing population of online gaming.”(17). Besides using biblically themed usernames and chat, their evangelization efforts also included aspects of performative “meekness” in their gameplay style, eschewing violence and action, as a way of demonstrating the proper Christian behavior within these repurposed digital venues. Men of God International chose where to send their volunteer missionaries according to their perceived scale of potential audience, and then improvised the technical feasibility of their mission within the game once they arrived there. The result was an interesting case of co-opting an engine of indoctrination from one belief system for the use of another.

Much of the history of American Evangelical Christianity’s relationship with video games involves appropriation of commercially successful secular gaming technology. Wisdom Tree was a company dedicated solely to this method as their development process. One of their games, Super Noah’s Ark 3D, was a modification of Wolfenstein 3D, in which images of Nazis were replaced with images of animals, and images of bullets were replaced with high-velocity “sleeping berries.” Another game, Bible Adventures, was based on Super Mario, replacing the collection of mushrooms with collectable slates featuring verses of the bible(18). Although Wisdom Tree never acquired the license to officially develop their games for Nintendo platforms, demand from parents was apparently enough to financially sustain the company for many years, and also instill a protective fear of parental backlash in Nintendo.

Like DARPA, Wisdom Tree and Men of God International exploited the practical tools and techniques of video game modding culture to implement their visions. However, as the medium of video games matured, a particular aura developed around the practice of creating them whole cloth. With the advent and popularization of video game journalism, game developers and game development gained media attention, and it became possible for the mythology around the development of blockbuster action games to spread farther and faster in the cultural consciousness than content of the games themselves. The press around the development of a video game development could become a significant media object in and of itself. Certain genres and levels of production value had strict expectations for magnitudes of labor required, and any ambitious development efforts outside the norm became worthy of a media event. With these media events came attention that made for new channels of propaganda, completely separate from the content of the software.

Left Behind: Eternal Forces was a 2006 top-down real-time strategy game set in the world of Left Behind, a young adult Christian fiction series. Developed by Left Behind Games, an independent studio founded by video game programmer Troy Lyndon, the game involves players leading squads of militia and missionaries through the ruins of a post-Rapture Manhattan, the goal being to convert as many pedestrians to Christianity as they can in the process of resisting the “Global Community Peacekeepers,” an international organization represented as street-musicians and monks acting on behalf of the antichrist. The battleground was set in New York City, but the territories to conquer were the souls of lost and vulnerable “neutral” New Yorkers, who needed be recruited and trained in order to contribute to spiritual warfare.

Left Behind: Eternal Forces was technically and logistically unprecedented in terms of Christian video games history. A privately funded effort featuring an original game engine and design, the scale of production for Left Behind: Eternal Forces was a dramatic departure from the previous methodologies of ideological modification, like that of Wisdom Tree. Although the game sold poorly and never made up for the cost of production, it became widely known and discussed for the public outcry it caused(19). The game featured militia units that could be used to kill any character resistant to religious conversion. Left Behind Games argued against criticism by saying that murder was “discouraged” by the use of a point system that penalized killing(20). The original version of the game allowed male characters to be assigned roles as soldiers, medics, musicians, builders, or evangelists, but limited female characters to only the “medic” or “musician” roles. The game developed enough infamy that when an unaffiliated advocacy group announced they were using their relationship with the “care package” programs of the Iraq war to mail copies of the game to US soldiers, the military quickly preempted the effort to avoid a possible PR mess(21).

These examples illustrate a few of the many aspects of institutional co-opting of new media. This is not to argue for technological pessimism, but to reaffirm a conceptualization of media and technology that is aware of, but not paralyzed by, the possibility of incorporation into an apparatus of institutional norms(22). As emerging technologies of the present continue to promise revolutionary utopias both personal and societal, their possible uses in reinforcing institutional powers and institutional norms must not be overlooked. Today, America’s Army: Proving Grounds is still downloadable on Steam(23), but the Army still has serious issues with recruitment(24). It has switched focus from violent video games toward social-media based efforts at aligning with millennial and Gen Z culture. Recent efforts include sponsoring CrossFit events and Twitch streamers and instituting Instagram posting quotas for their recruiters(25). Some early experiments in sponsoring Esports for games such as Fortnite are occurring as well(26). Culture moves on with the new, and so do the powers that be.

luming hao is a student at ITP and an alumni of the School of Poetic Computation’s Code Societies Program, with a background in computer programming and music theory.