Issue 5: Reality?

Small Mirrors of the Real

Small Mirrors of the Real

By Sam Hains

Illustrated by Sam Hains

As IRL experiences become increasingly absorbed into the digital, we find ourselves fighting against becoming consumed by the simulation as well.

Media theorist Wendy Chun once differentiated the computer from other tools and formal systems through its relationship to simulation and simulated worlds. “While most tools produce effects on a wider world of which they are only a part, the computer contains its own worlds in miniature” (1). Computer worlds, like those of children’s make-believe, grant absolute power to whoever is imagining or programming them (2). As reality is drafted into digital environments, the computer simulation offers the opportunity to create worlds and bodies without unwanted complexity. It allows us to devise private games and internally consistent worlds in the face of absurdity and paradox. Advances in computer imaging technology towards “photorealism” further seduce us into believing that we are looking at concrete realities rather than ideological assemblages of math and code. As reality is increasingly reflected through the small mirrors of digital simulation, we risk losing sight of the mysterious nature of our lived reality.

Simulated bodies

Since the early 1970s, the human figure has been rendered and visualized in digital environments as an interactive 3D model. By the 1980s, a team at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Human Modeling and Simulation developed the first “computer graphics surrogate human,” called Jack. Jack was born from the analysis and synthesis of body scans of 89 subjects. While analog humans typically make use of 360 joints for their daily functions, Jack requires only 68 (3). His highly simplified form is all that is needed to infer human presence among computational problems and constraints. To this day, Jack remains a “premiere human simulation tool” for populating designs with virtual people and performing human factors and ergonomic analysis (4). Through Jack, the standardized interface of industrial production line was granted a standardized, automated operator. He represents the human blending into the production line as an automaton; alienated by an increasingly technological culture.

Simulations are instrumental and emotionally appealing for the same reason; they enable the authoring of worlds without ‘irrelevant or unwanted complexity’ (5, xix). But what aspects of human feeling and experience are left out?

Simulated worlds

Some simulations aim to model the human world, drafting its form into digital formats that can be experimented with. These simulations often appeal to their audience by providing an interactive environment for fantasy fulfillment. Unlike the utilitarian approach to computer graphics of the corporate simulation, video games embrace the seductive qualities of graphic realism. The closer these environments move towards realism, the more the model begins to resemble the reality it points towards.

Artists have played a significant role in critiquing these increasingly “realistic” simulations. In Georgie Roxby Smith’s virtual performance “Run Like A Girl [Fair Game],” she examines the behavior of the “stereotyped female bots” who populate Grand Theft Auto’s simulation of California. Despite their initial attitude, the bots “screech and run like a girl” when touched by their male counterparts (6). While these animations are designed by the gamemaker to be fleeting and momentary, Smith seeks the endpoint for their behavior. By probing the boundaries of the simulated world; she reveals that the women in this simulation are programmed for little more than performative fear and death. As we retreat from the overwhelming complexity of our lived experience into synthetic, entertainment-driven worlds, we risk losing sight of the violence and bigotry exacted through simplified models of reality.

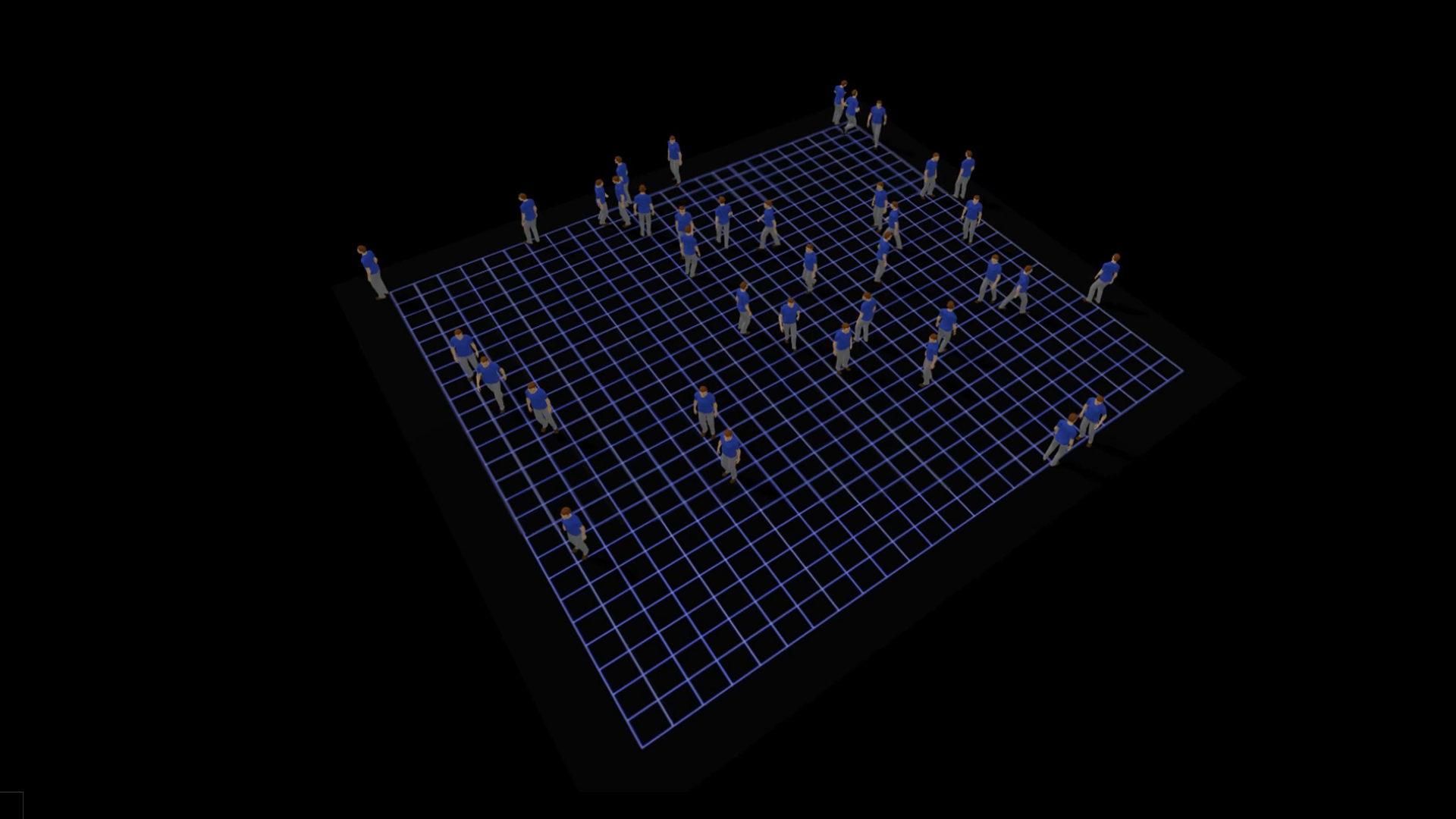

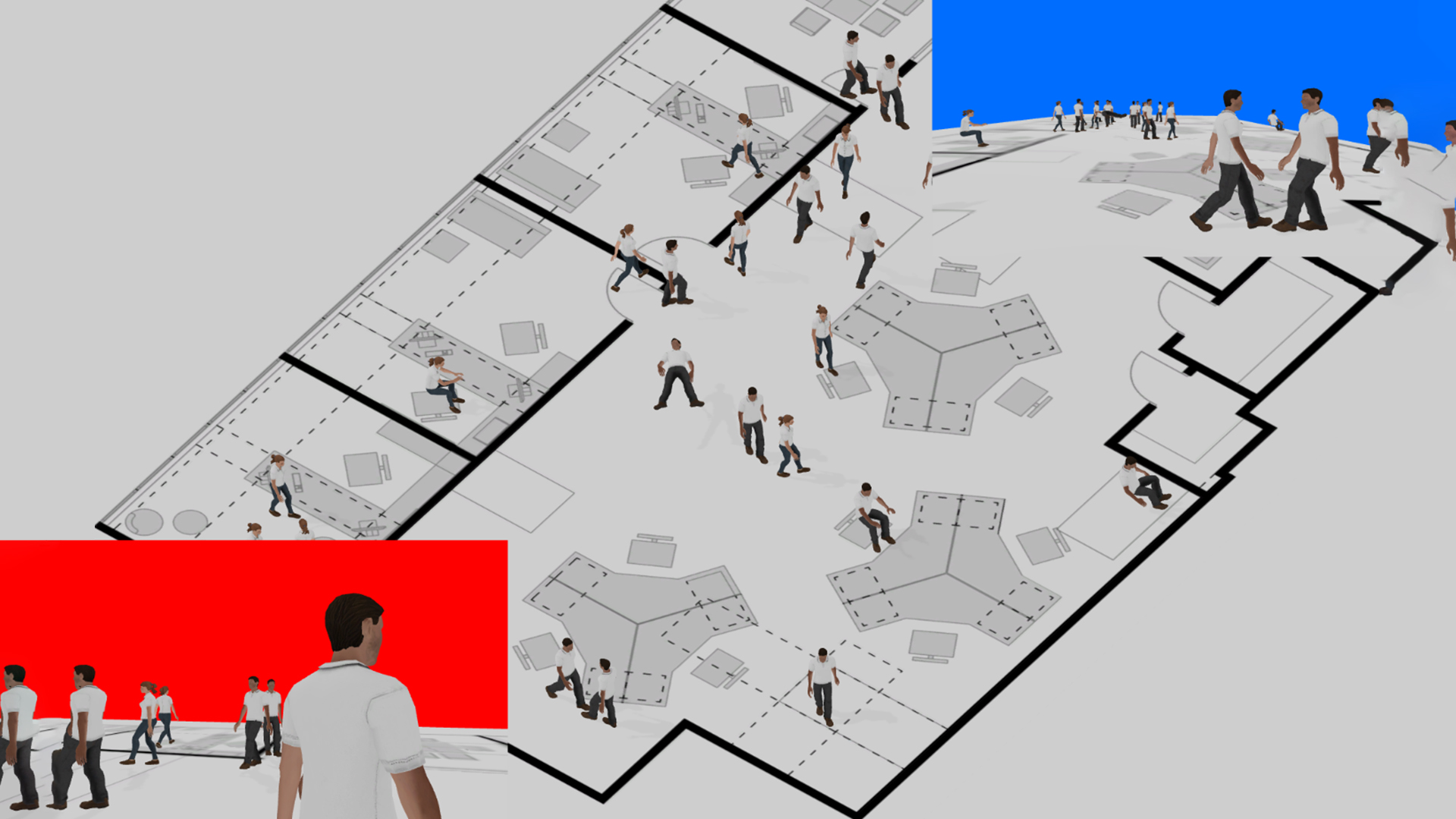

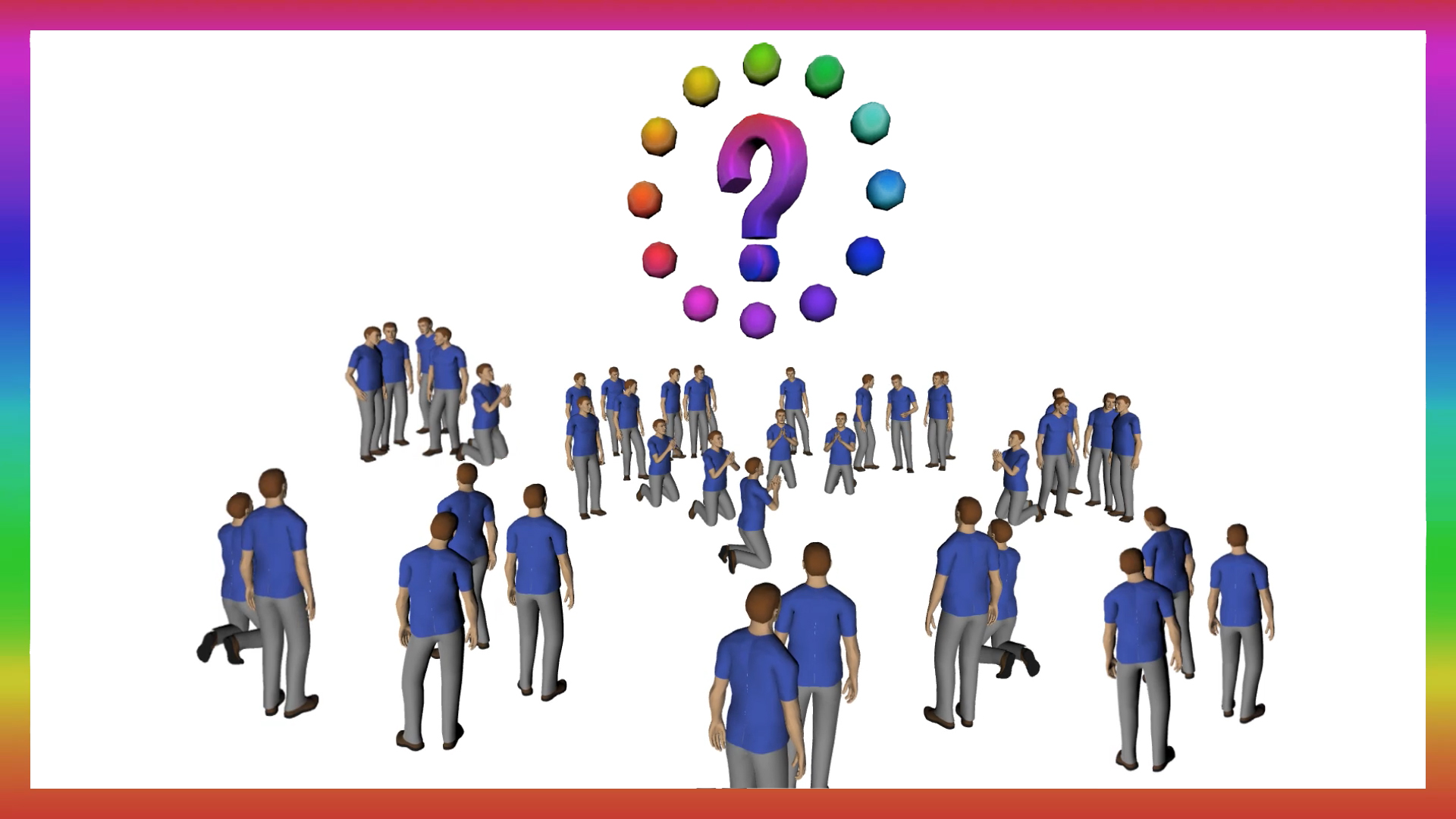

In 2018, I created a real-time simulation called “Island of Task Executors” about Jack, our computer-generated “human surrogate,” and his dystopic, homogenous existence. The assets for this project were appropriated from corporate simulation software called FlexSim. Through this work, I sought to interrogate the meaning of an agent who had been intentionally programmed without human feeling.Through simulated body language, musical accompaniment, and narrative framing, I discovered that Jack could be choreographed to evoke a sense of his own trauma: Jack is troubled. Jack is disturbed. Jack is stuck. Jack has a void within. Jack is aware of the simulation. Wait a second — am I Jack?

By the end of the project, I realized that Jack was an allegory for my own precarious sense of reality. We are both agents in an absurd world programmed by larger, more powerful reality constructs.

Simulated minds

The drafting of reality into simulation proves instrumental for predicting and modelling more internal and social aspects of the human psyche. This kind of simulation presents itself not only as desire fulfillment, but as a function that has become integrated into everyday life through social platforms such as Facebook.

The digital interface of social platforms plays an essential role in seducing users into the simulation. Unlike video game worlds, social media platforms do not rely on graphical realism for their seduction. By capturing “lives, likes, and allegiances” of its active users, Facebook creates a model for each user capable of evoking their desires and fears (12). Each user has a “data double” (7) – a simulated homunculus in the Facebook servers, watching, learning, and pre-empting their behavior in real time.

Unlike video game worlds, social media platforms do not rely on graphical realism for their seduction.

In 2017, a 23-page internal document from Facebook was leaked outlining the platform’s capacity to target young people in moments when they “need a confidence boost” in “pinpoint detail” (8). The document stated that Facebook can work out when young people feel “stressed,” “overwhelmed,” “nervous,” “stupid,” “silly,” and “useless” by monitoring posts, pictures, and internet activity in real time (9). By simulating the detailed emotional states of its more vulnerable users, Facebook is capable of delivering targeted messages at the moment of maximum impact. The interface disguises the process, maintaining the reality and illusion of a “well-pruned, curated live stream” (12).

This integration of the simulation into our everyday lives was considered by Baudrillard as an emblem of a shift in relations between reality and its simulation; a media that projects reality rather than merely representing it. Computer simulations are maps that become territories. The simulated object transcends the binary opposition of “authentic” and “fake,” “original” and “copy” (10) — the technological simulacrum creates its own reality.

As the simulation and its representation collapse into itself, we might also wonder whether theory itself is a kind of simulation. Another microworld, programmed in accordance with the laws of the theoretician. Like any simulation, theoretical worlds are capable of spilling out and influencing the reality they attempt to model. Rather than being determined from outside, simulations bring into being the realities that they intentionally model.

The struggle for authenticity and humanity within a simulated landscape has been a central concern in science fiction since its inception. The disintegrating realities of Philip K. Dick’s writing explore connections between ontological constructions in fictional worlds and ideological constructions of a broader reality. In his short story “Electric Ant,” Garson Poole wakes up to find he is an “organic robot” (11). He is not a human, but rather a machine whose subjective reality is a simulation being fed to him through a tape in his chest. Poole’s “false reality” offers a metaphor for the media technology that organizes and frames our everyday experience. The human psyche: a screen upon which larger and more powerful constructs project their deceptive systems.

As the seams of the simulation come unglued, new possibilities for experimentation are revealed, and a space for deeper novelty and authenticity emerges (10). Poole is granted the ability to experiment with the machine that produces his reality, introducing or removing elements as he pleases. By exploring the psyche as simulation, we begin to notice the various ways in which it is composed of psychological, social, and linguistic constructs. Beneath the constructs vying to simulate our experience, Dick points to a highly personal cosmic experience; that which cannot be digitized or simulated.

Conclusion

The danger of simulations, and systems more broadly, is that they tend to seduce us into mistaking our models of reality for reality itself. The simulation is a logical construction; a rationalist drafting of reality into the digital. The internal consistency of the microworld creates a sense of meaning and satisfaction by effacing some of the complexities of lived reality. Despite photorealistic graphics and uncanny data doubles, simulations inherently simplify the objects they represent.

As we find ourselves inside digital realities, we must remain critical of their mode of simplifying lived experience. As seductive as simulated worlds and minds become to us, we must remain committed to aspects of the human experience that are authentic and non-quantifiable.

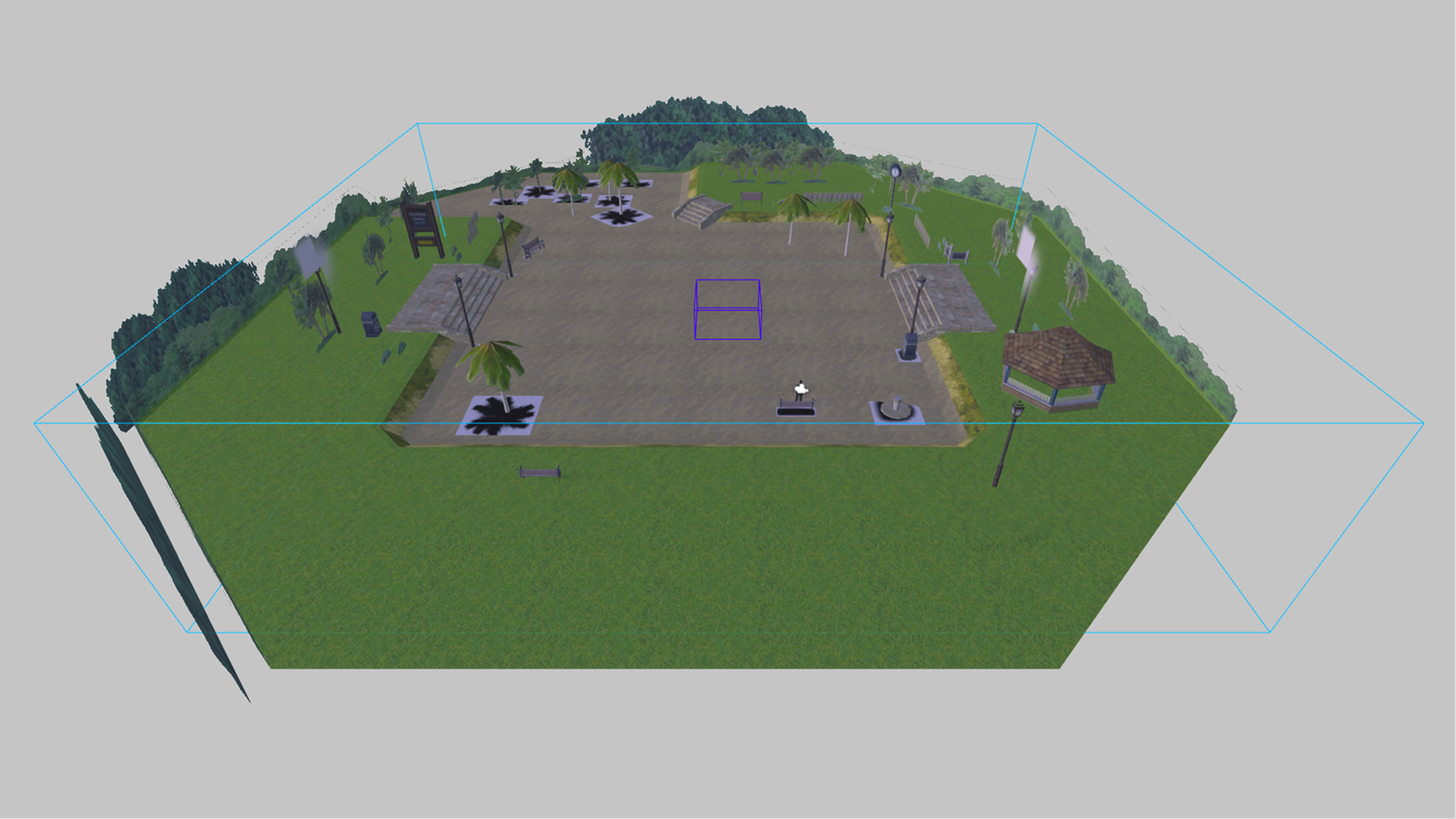

When we zoom out on the video game environment, we see a disc floating in the space. The simulation may stage a seductive, virtual theater — but do its objects matter? The world itself is a kind of construct, a veil of illusion that is masking a true landscape; a true reality.

1. Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. “Programmability” Software Studies, 2008, pp. 225–228.

2. Edwards, Paul N. “The Army and the Microworld: Computers and the Politics of Gender Identity.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 16, no. 1, 1990, pp. 102–127., doi:10.1086/494647.

3. N. I. Badler, C. B. Phillips and B. L. Webber. Simulating Humans: Computer Graphics, Animation, and Control (Oxford University Press, 1993), 27-28.

4. “University uses Tecnomatix human modeling and simulation in undergraduate research studies” Siemens PLM, 1 May 2018 https://www.plm.automation.siemens.com/global/en/our-story/customers/penn-state-behrend/35058/

5. Crogan, Patrick. Gameplay Mode: War, Simulation, and Technoculture. University of Minnesota Press, 2011

6. “Selected Works” Georgia Roxby Smith, 1 May 2018

7. Scherzinger, Martin. “The Executing Machine:” Dark Precursor, 2017, pp. 36–55., doi:10.2307/j.ctt21c4rxx.5

8. “Facebook targets ‘insecure’ young people” The Australian, 1 May 2018 https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/media/digital/facebook-targets-insecure-young-people-to-sell-ads/news-story/a89949ad016eee7d7a61c3c30c909fa6

9. “The Last Days of Reality.” Meanjin, 22 Apr. 2018, meanjin.com.au/essays/the-last-days-of-reality/

10. “Philip K. Dick’s Divine Interference.” Techgnosis, 25 Oct. 2018, techgnosis.com/philip-k-dicks-divine-interference/

11. Dick, Philip K. The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick. Subterranean Press, 2014

12. Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: on Software and Sovereignty. MIT Press, 2015

Sam Hains is a designer and A/V technologist working at the intersections of theatre, video installation and artificial intelligence. His artwork primarily focuses on the relationship between worlds and simulations. By developing his own pseudo-worlds, or video simulations; Sam explores the ways in which reality is manufactured. His work has been featured in The Creators Project, Neural Magazine and The Wrong Biennale. He is currently the projection and interaction designer for an Off-Broadway production called #DateMe.