Issue 3

Taste, Touch, Tech: An Interview with Mattia Casalegno

There’s something about encountering an artist’s work before meeting them in person, because you can’t help but make assumptions about their personality. And sometimes you are right! My expectation of Mattia Casalegno was that he would be quick-witted, ingenious and have a sense of playfulness. And he lived up to my expectation.

Mattia Casalegno at his studio. Photo by George Gillpin

When I visited Mattia’s studio for the first time, I saw a 3D-printed bird twisted in front of a wooden board and two antennas wrapped in hot pink neon lights. The board and antennas represent a television in such a ridiculous way that it becomes a brilliant mockery of outdated technology—a fascinating analogy to how we treat and are treated by the mediated experiences from numerous screens in our life. The Internet never seems to be the liberation from the dictatorship of televisions, nor do interactive artworks let the viewers be in control. But the illusion that technology would rescue postmodern human life from the sufferings of technology per se are precisely addressed in this piece. Optimism and absurdity are present at the same time—finally with the help of 3D-printing a physical bird is present, but rather than a real bird, it is the reproduction of the living creature’s digital model.

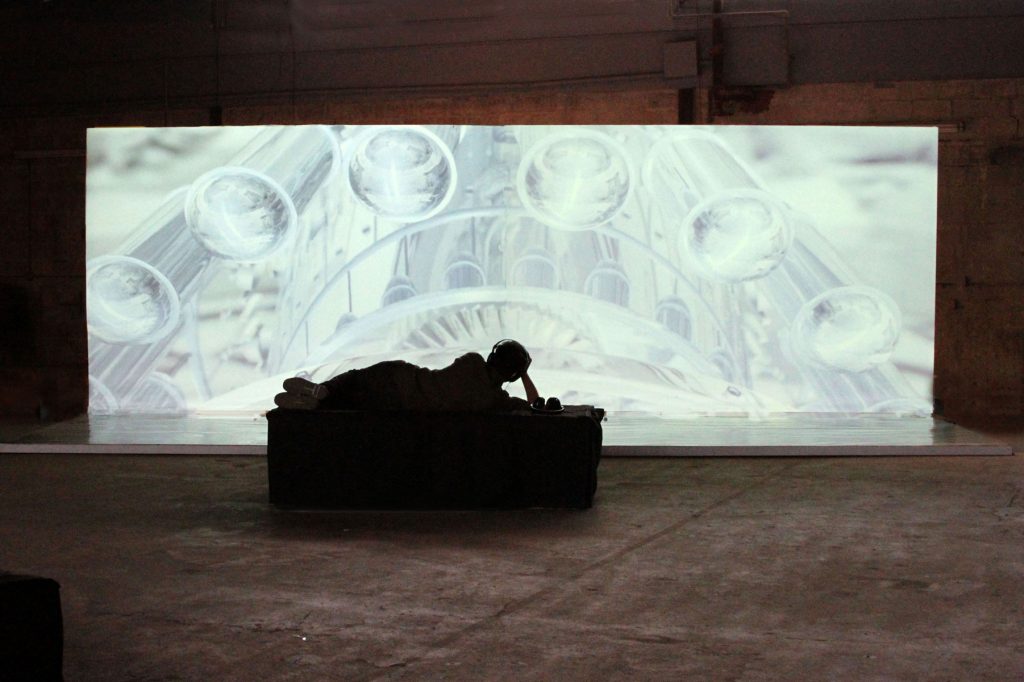

I had no idea when I met him that I’d curate a show of his work.I also didn’t know that at the opening an improv performer would unpredictably throw toilet plungers around his classic sculptures 3D-printed with Soylent while yelling “Just because it’s an art gallery, how would I know that there is art.” Ironically looping in the background was Mattia’s video-sound piece Left-Handed, in which a glitched spaceship-like machine invades the stagnating display of Renaissance statues. The performer became a rebel against the rebel. I titled the exhibition Dyspepsia, to help him accomplish the existential intrusion into the contemporary human body that was inherited from those stagnating ancient forms. As Friedrich Engels once said: “Only barbarians are able to rejuvenate a world in the throes of collapsing civilization.” Mattia Casalegno–artist, barbarian.

Left Handed (2016), installation view, The Projects, Fort Lauderdale. Image courtesy of the artist.

Aside from the Soylent project, food/dining is in fact a recurring theme in Mattia’s oeuvre (also he is one of the very few people I know who leaves decent comments for restaurants on Yelp). His kinetic sculpture RBSC.01 manufactures sacramental bread while the viewers get to receive Communion made by a machine; and in his latest solo show in Shanghai, The Aerobanquets RMX, he literally threw a feast and invited strangers to have dinner accompanied by the experience of virtual reality.

There’s something human about his works in a classy and almost old-fashioned way that is rarely found in other new media artists’ work which are often odes to technology. In Unstable Empathy, two participants sitting in complete darkness are able to hear each other’s mental activities through sound and can see their own facial expressions projected onto the other person’s face, however in the end the twisted digital phantoms disappear, the shelters for participants to sit in are lit so that they can see each others’ authentic facial expressions and realize how short the physical distance between them really is.

As Ennio Bianco, the curator of Mattia’s show at the Civic Museum of Bassano del Grappa in Italy once claimed, that it was the high aesthetic value in Mattia’s work, which might even be called ‘beauty’, that made him choose to show them. What could be more radical a statement in a world of anti-sentimental machines than to value the instinct of appreciating beauty? Modern and contemporary art has gradually become more and more reluctant to embrace beauty, considering it a superficial, bourgeois value while defining true art in abstractions such as big ideas, politics, the sublime. Mattia, and his fellow artists of our generation on the other hand are trying to break such long dominating bias by seeking an alternative expression that admits the coexistence of both.

The Aerobanquets RMX (2018), installation view, Chronus Art Center, Shanghai. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tansy Xiao: Tell us about your new exhibition The Aerobanquets RMX in Shanghai.

Mattia Casalegno: The Aerobanquets RMX is a series of augmented ‘sensorial experiences’, loosely based on The Futurist Cookbook, an Italian book of fictional dinners and surreal recipes first published in 1932. It’s a project exploring the relationships between immersive technologies and perception.

The Futurists were among the first European avant-gardes to conceive a total work of art encompassing all the senses—vision, hearing, touch, olfaction and taste. So while reading the cookbook, I started thinking about a project using immersive technologies that would touch on all the senses. It’s a collaboration with Flavio Ghignoni Carestia, chef at the Toscanini café in Amsterdam, with whom I created an original menu and a dining experience in virtual and mixed reality.

TX: Some say that VR is blocking one’s access to the real world. How did you manage to connect people to the real world with their sense of taste?

MC: It is true, in VR your visual experience is confined within a headset, but there are already many new technologies related to VR that go in the direction of involving other senses: augmented reality, haptics, hands tracking, etc.

For the Aerobanquets RMX we used a room-sized motion tracking system that allowed the audience to use utensils and objects and interact with them both in the physical and the digital world. I was interested in VR not as much as a storytelling device, but as an interface enabling different ways of perceiving. The perception of taste created in your brain is not only affected by the taste buds but also by your vision, olfaction, and touch. How would taste change when your eyes are seeing something else?

The Aerobanquets RMX (2018), installation view, Chronus Art Center, Shanghai. Image courtesy of the artist.

TX: This is not your first project with an edible outcome. From your personal experience, how do you feel about the act of eating/dining as a social activity? Is the idea different across cultures?

MC: I think eating is regarded as a social activity in every culture. Many rituals are centered around the act of eating or sharing a meal. It might have changed a bit nowadays as we live more frenetic and individualistic lives, but eating should be social. Eating alone is sad.

TX: On the other hand, the piece RBSC.01 is not only about eating per se but showing the process of producing a piece of bread in a liturgical context. Can you talk a bit about that piece?

MC: RBSC.01 is a 11 feet tall kinetic sculpture designed to produce and stamp a logo on a thin, round unleavened wafer of edible bread resembling a communion wafer.

The title of the piece is inspired by the RuBisCo, a key enzyme used in the photosynthesis (or ‘Calvin Cycle’, i.e. the chemical reactions used by plants to obtain their nutrient from water and solar energy.)

The inspiration for this piece came from the idea of ‘consecration’, as used in many religious rituals. We consecrate something when we take a normal object and decide that it’s divine, sacred, which is everything set apart and forbidden. The French sociologist Durkheim says that the sacred, embodied in symbols and totems, represents the interests and unity of the group. The profane, on the other hand, involves individual concerns and personal interests. So I thought about relating these ideas to the relationship we have with our planet. The number one problem I think is that we do not regard our environment, our natural resources and the other living organisms as something that is in the interests of the group, of all of us.

How can we bring the sacred back into nature? How can we bring it back to a level that we can all relate to? In RBSC.01 we have a machine that literally makes a sacred symbol that you can ingest, making it your own.

RBSC.01, kinetic sculpture with custom electronics, 2011. Image courtesy of the artist.

TX: In fact I’ve noticed that strong sense of ritualistic undertone in many of your other works, like Unstable Empathy, which digitally maps participants’ mental activities onto each other’s faces like dynamic tribal tattoos.

How do you feel about the relevance between inherited rituals and contemporary technology, and in particular how did the audience react to Unstable Empathy?

MC: In a way, we have always made sense of our role in society through technological enhancements. I’m thinking about the intricately decorated masks deployed in many indigenous rites, or how we use our social media handles in the daily micro-rituals of posting and tagging.

Unstable Empathy is an installation designed to enable an intimate experience based on the real-time monitoring of the mind activities of two players, who are constantly forced to negotiate their ‘empathetic’ state.

In each session, EEG headsets are being mounted on two participants, positioned in front of each other in complete darkness. Each player hears a rhythmic sound based on his and the other’s brain activity—the sound slows down when you are calm and present, and ramps up when the opposite is the case. With the intention to ‘sync’ the two sounds, the players develop their own methodology of interaction, and would finally discover their own physiognomies superimposed onto each other. The piece is an attempt to achieve a sort of ‘empathetic’ connection, a deeper understanding of each other without language.

Unstable Empathy (2012), installation view, Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei. Image courtesy of the artist.

TX: In addition to chefs, you have collaborated with many specialists in various fields: musicians, biologists, ecologists, neuroscientists, and astrophysicists. How was it like to communicate with people from such disparate cultural contexts?

MC: I think art is not only about mastering a specific craft, but also about crafting new concepts, having an inquisitive look and actually being able to make a real difference in the world. It’s more like an attitude towards life and knowledge. This is true for any discipline, really. Whether you are a scientist, a philosopher, an athlete, or something else.

In that sense, even though a scientist works in a different context and with different tools, we may be seeking similar answers, and we can both learn from each other’s research.

TX: Which one do you think was the most difficult collaboration so far?

MC: I’ve always had meaningful and productive collaborations. Some projects are more complex and time demanding than others, but that depends on the nature and the aims of each specific piece.

TX: Your work never relies solely on a digital platform. The relationship between the viewers and their environment always plays an essential part. What sparked your interest in immersion and space?

MC: Theater is a big influence in my work. Many artists I was inspired by, and whose work I admire and study, come from performance and theater. I always approach my work in terms of space and image, even if it is as immaterial as a digital video, or an experience.

In my installations I often put the audience in a state of imbalance, discomfort, or even of perceived danger. When you’re slightly uncomfortable, not situated, your senses are enhanced, more open, and receptive.

TX: What happens to one’s body after their senses become more open? Will the discomfort turn into something else in the end?

MC: When you’re not situated, not at rest, you are more aware of your surroundings in an instinctive way, and you will perceive things more directly.

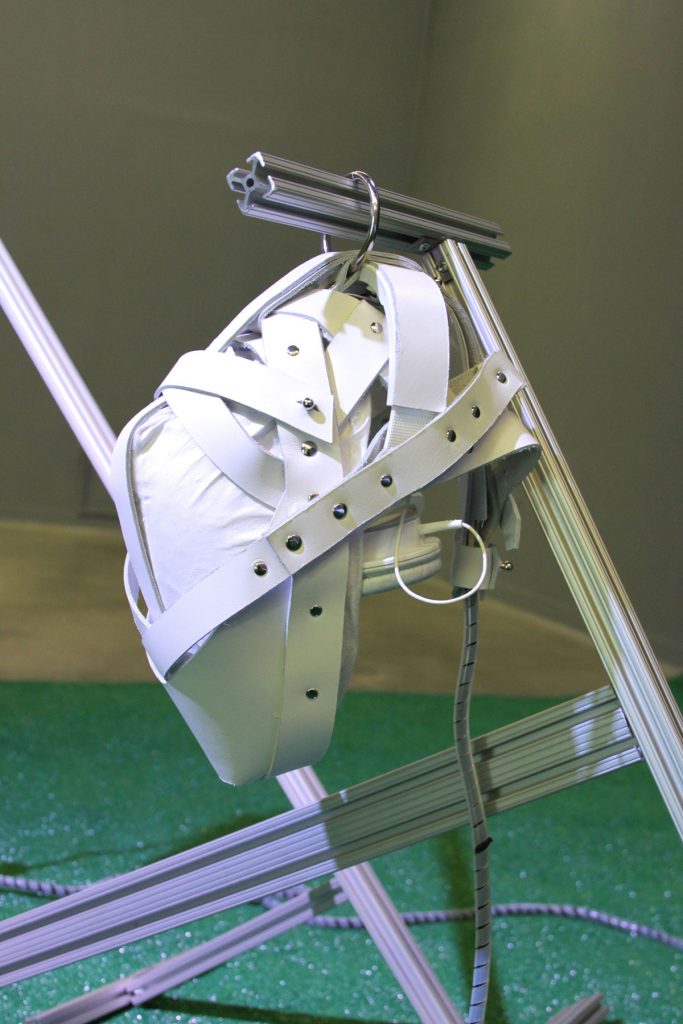

The Open for example, a project I started in 2011 in collaboration with the design studio Metonym, consists of a mask that wraps around your head and literally constrains your entire visual experience. The mask is lined with Green-leaf volatiles (the chemical released by grass just after it has been cut) and incorporates headphones that replays the sound of your own breath with a slight delay. It creates an intense physical sensation that oscillates between a sense of primal safety as if in a womb-like, enclosed space, and a sense that evokes the fear of being buried in darkness.

The Open (2011-present), detail, Young at Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale. Image courtesy of Shani Pak.

TX: When you work with wearable and interactive devices, do you focus on the experience of the participants, or do you consider the participants’ theatrical function as related to other viewers as well? How do you balance the two, and which one is more important if you were to choose?

MC: I think about it both ways. I think in terms of activating a space. An ‘activated space’ can be a few square inches or several square feet, but what I focus on is the relational potential of the audience who experience the work. I’m also interested in what the work becomes after that first stage, the entire life of the work in a way.

Performances and installations are temporary by definition, and a lot has been discussed about the role of documentation. But if you think in terms of theater, staging, and image-making, you realize that the documentation is actually part of the work itself.

Most people will experience a temporary work through its visual traces—official photos, Instagram, Facebook posts—and these images ARE the work in the minds of these people. So the question is, how do you create temporary work that’s meaningful in terms of the experience, but also in terms of the images that will represent it through history?

TX: Your new 3D printed sculptures made with perishable materials such as silicone and Soylent are remarkable. You previously focused on the process rather than the result, either in your performances, kinetic installations or participatory art. What made you decide to create these relatively ‘quiet’ pieces, and how do you like the outcome?

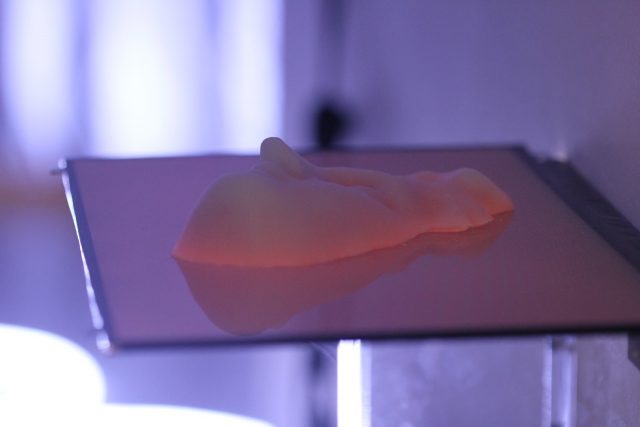

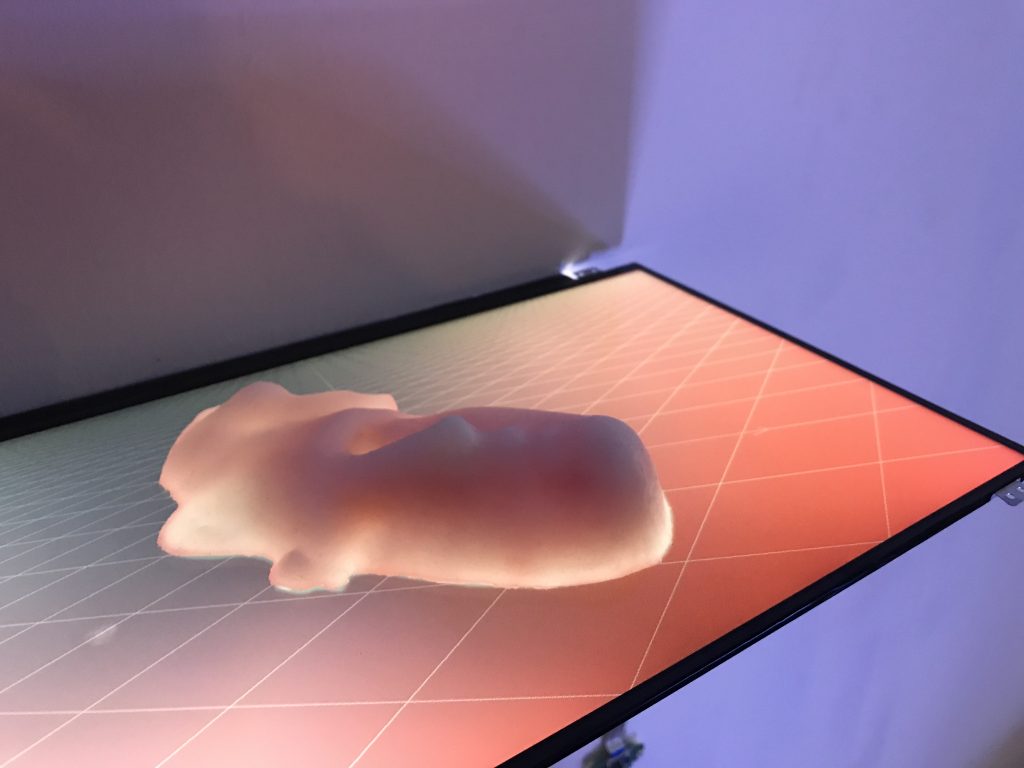

MC: The sculptures are part of a project commissioned by the City Museum of Bassano del Grappa, a small town near Venice, Italy. The museum hosts one of the biggest collections of the sculptor Antonio Canova, one of the greatest Italian Neoclassical artists in the eighteenth-century. His marble sculptures notoriously depict bodies that are flawless, spotless, and god-like, and his work for me is about the human body in a very contemporary way. It reminds me of how advertising sells us an image of the body that is hyper-performative, upgradable, and unreachable, striving for an ideal perfection, which is very much fictitious. So I started to work with materials that are metaphors for the way we relate to our bodies: silicone, which is used in implants and body augmentation, and Soylent, a powdered food marketed as the ultimate “food for the space age”.

Knowledge of the Body (2018), detail, Dyspepsia, New York. Image courtesy of Tansy Xiao.

TX: It is a bold statement nowadays to use the words ‘aesthetics’ and ‘beauty’ in the context of contemporary art. How do you feel about this in relation to what you value in your own art?

MC: I think beauty is necessary as an entry point to an artwork. I think in art you still strive for beauty, but the canon of beauty is changing. We see beauty in many different things now. We also unfortunately live our lives more and more detached from the natural world, and we are still very much grasping a new idea of beauty.

But isn’t art exactly this quest? A search for new propositions of what beauty might be?

TX: What are your next steps? Are you working on new projects or ideas?

MC: I just recently came back from a two-months residency in China, so I’ll be spending the next weeks or so to pick up the threads of my ongoing studio projects. I won’t share too many details now but, I have several exciting projects coming up. Stay tuned!