Issue 2

The Temporary Expert: A Toolkit for Artist Activists

1 – Slurb, 2009. 18’ loop. Courtesy the artist and bitforms gallery.

If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?

– Albert Einstein

Introduction

O er the past 11 years, I’ve developed an art and research practice that focuses on climate change, the Anthropocene1, and in particular explores near-impossible nature-culture intersections, including invasive species, our interdependence with fossil fuels, and our dualistic relationship with oceans.

In my evolving work as an art and research practitioner, I have what I view to be two obligations:

- To follow my curious spirit and love for making; and

- To respond to what I define as moral, ethical or personal obligations.

The exigency of climate change, the political urges to suppress information on the present realities of the environment, and the unevenness of the effects of both of these phenomena can drive an artist (or anyone) to depression and a feeling of uselessness. Below, I outline a strategy for an art and research practice that encourages those feelings to become tools, illustrated with concurrent examples of my own work.

This is a manual in no particular order, intended for those who want to work a topic to death and back to life again. It is for artists interested in ‘research-based practice’, and has evolved from The Temporary Expert: Research-based Art and Design Practice, a class I’ve taught at NYU/ITP for the past four years.

The Practice

A Temporary Expert possesses a suitcase of tools, perspectives and surprises. These are tools and viewpoints to aid in ‘deep-diving’, and becoming unstuck. Start by identifying the content of your research. This includes your desire, urge or subject of interest. Define the media and material. What will your work be made of? Identify your audience and participants. Who is your work made for? And how will you reach them? Finally, know your kin. What projects, practices and people (dead or alive) are the relatives of your work?

Temporary expertise involves a variety of deep research. All art practices are based in some facets of research, whether you are aware of them as research or not. I’m using the term ‘research’ broadly, to include varied epistemologies including experience, scholarly works, common assumptions, historical associations, and material explorations, to name a few.

My first works to address the climate, flooding, and the ‘picture-space’ of climate change were lyrical animations (Boom! Darling, The Poster Children, Elixir I-IV, Slurb). My research was solely directed online; I was looking at how stories of flooding, ewaste, icebergs and polar bears, and teen shooters were being represented (and territorialized) by the media. I remixed them into new, uncomfortably candy-colored scenes and contexts. The work trafficked in enchantment and metaphor, the languages of painting and cartoons. I knew a lot about the science, but you wouldn’t necessarily see it in my work. I did many public presentations of this work, which helped me articulate and share my intentions and give context to the pieces.

Temporary Experts travel several roads at once. Research is sometimes best done in analogous fields. What’s your research subject like? What’s it not like? Start broad, read widely, see what sticks, and exercise analogy.

In 2009, I applied for a three-week artists’ research residency at Isis Arts2 in Northern England. My goal was to investigate the relationship between invasive species and xenophobia. This was not an original thought: I had read a long piece in The New York Times about the alarming rise in American Gray Squirrels in England wiping out native Red Squirrels. My investigation found complex stories of resource management, as well as connections to xenophobia. I wanted to go to the UK and get offline, to see what would shift if I actually spent time on the ground, and set up some protocols for myself—rules for engagement and setting intentions to push past my familiar territory of practice. These rules included: lining up interviews with scientists and artists working in art/science contexts; visiting historical archives; reading about the history of the land and taking tours. There were also some limitations: I would spend some time in the studio, and produce only a few sketches while there. It was a fruitful 3 weeks with a loopy, engaged, alien and singular focus.

That year I had also started a blog dedicated to research, in order to leave a trail of documentation. Although I began before I left for England, the activity of keeping daily track of my questions, speculations, and activities that took shape in the field solidified my experience. The result was a record of process, but also a repository of contacts and associative thinking that would otherwise be muddy or dim.

Out of this residency, I produced a suite of work under the title Friends and Enemies, consisting of a 144 hour-long procedural animation (Mesocosm, Northumberland, UK), and 12 letterpress prints titled Heraldic Crests for Invasive Species.

Temporary experts conduct traditional research. Neither art-making experiments nor traditional research are enough on their own. The alchemy comes in the discoveries from navigating these two paths of inquiry. Of course read about your subject. Use the library or Google Scholar, and observe popular search news, but do not rely on on the internet alone. Wikipedia is a fine start point, but then you need to pull long threads, and fact check your findings. If you read something exciting online, see who else has written about it. If you find nothing but identical information, be wary.

Temporary Experts find kinship in other experts and amateurs. Who else has made work about your subject? Who else has made work using your media, and for what purposes and directed toward what kinds of audiences? This is not imitation, it’s conversation. Seek out these people, and connect with them.

My dreams of engaging audiences to reconsider our relationships with what we call ‘Nature’ began to creep out of the box of pictorial spaces. I needed a broader toolkit to engage audiences and to offer different kinds of encounters. I began to collaborate with programmers, chefs, and writers. My research more actively incorporated academic writing—in what’s known as ‘post-natural’ or ‘post-humanities’—such as the works of Bruno Latour, Donna Haraway, Timothy Morton, Una Chaudhuri, and Jane Bennett. I sought out people who spend their time thinking and teaching about these things in Environmental Humanities and Animal Studies Departments. I even wrote Timothy Morton a fan letter when I made the first Mesocosm piece, as I had named it after a tiny passage in his book Ecology Without Nature, which was exciting and moved my thinking somewhere else. (Gratefully he responded, and we have become friends).

Conferences such as Society for Literature, Science and the Arts (SLSA), and Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) also shaped my thinking and offered language to describe ways of forging new environmental relations and perceptions.

Temporary Experts are generous with their research partners and subjects. Every exchange is a relationship or potential partnership. Interview subjects are not objects. Be mindful of and thankful for their time. Do this by being prepared and knowledgeable. Follow up with more questions. Be a ‘gentle pest’ and always say thank you.

Temporary Experts experiment and explore. Get to know your subject in as many ways as possible. Cook it. Walk it. Bike it. Draw it. Animate it. Give it a character and have it keep a journal. Cultivate a daily practice. Talk to strangers. Trick and bore yourself. Explore and embrace dead ends. Put all of these items into your tool kit and hone them.

Many of the theoretical frameworks I’d accumulated opened my field research to new considerations. I conducted another research/field trip in 2011, into the petroleum landscape of West Texas. This two week research trip was expansive in scope, research questions, and the ways in which I opened up in the face of lived contradictions—redefining the terms of beauty and ugliness; good people who differed greatly from me politically, culturally and economically; the specific sensual qualities of place; and all the small surprises and nuances available only when you slow down and tune in to them, undistracted.

I was particularly interested in the idea of non-human agency, and set out asking questions of the landscape, like “What does petroleum want?” or “What does a drill bit see?” Over the subsequent 18 months I produced 11 animations, a seven-course meal for 50 people on eating hydrocarbons and geological time, two public engagement projects on interfacing with one’s plastic possessions, a book in collaboration with 40 writers, and several sculptural works.

Temporary Experts share their ideas. Put your ideas out there, even if you’re embarrassed. Make sure to get feedback. Move towards your weaknesses and imagine your project from multiple perspectives. Have a sense of humor.

Temporary Experts spread information. Consider how to get things into the hands of others—those who are receptive to what you might have to say but also those who aren’t. The arts contribute very slowly to paradigm shifts. But in order to change positions we need to change hearts. For this, there is no greater weapon than art.

Designers attempting to address a wicked problem must be fully responsible for their actions.

– Horst Rittel

In 2013, I audited a semester-long class—Applied Systems Thinking, taught by Howard Silverman at Pacific Northwest College of Art in Oregon. Systems thinking studies and maps systems and their boundaries—ecosystems, education and social castes are all systems. When applied, one can look for avenues of intervention by understanding where there might be leverage points. The term ‘wicked problems’ comes out of systems thinking: problems like waste, poverty or wellness that are so difficult or impossible to solve because the issue is bound through many systems, and a solution may beget a new host of problems. Horst Rittel, who coined the term, cites 10 characteristics of these mass conundrums. The final conundrum states: “Designers attempting to address a wicked problem must be fully responsible for their actions.” This call to account for complexity was a fundamentally shifted my work.

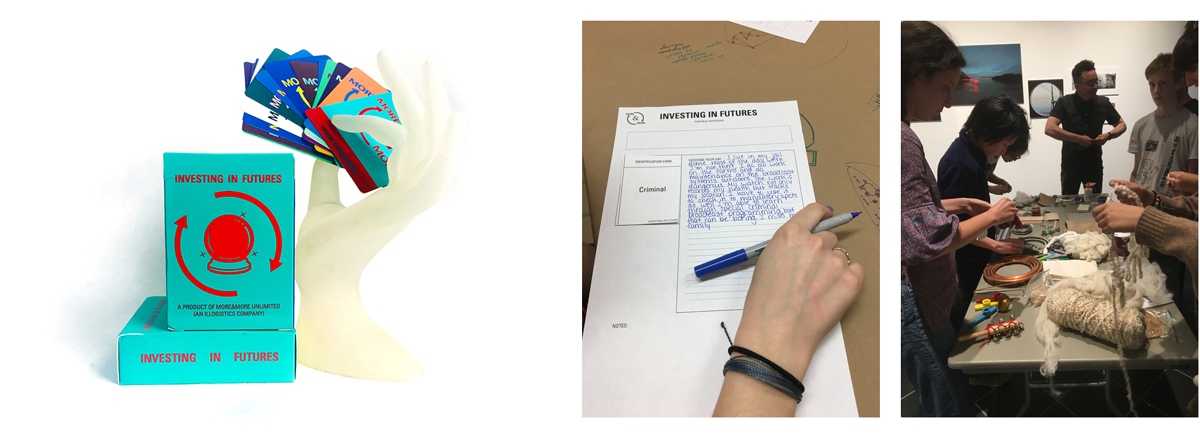

4 – Investing in Futures, 2017

Postscript

A ‘Temporary Expert’ could also be known as a ‘Permanent (enthusiastic) Amateur’. The word amateur unfortunately bears some shame; could this be used to one’s advantage? Amateurs make important contributions to bodies of knowledge, and experiment with vigor and freedom from the shackles of specialization. Think back to the studied medievalists and early enlightenment practitioners, who were not bound by highly developed protocols but made their own hybrid frameworks: Paracelsus, Da Vinci, Couvier, and the artists who have learned—and shunned—classical definitions of ‘good taste’ and mastery, as well as the more recent ones who employ camouflage and hybrid practices in order to create new frameworks for engagement.

As an artist and researcher interested in ‘naturecultures’,3 I am obligated to widen my scope and to understand the connections between the biosphere’s environmental shifts and economic, political, and social events. This is honestly overwhelming. I often revisit Donella Meadow’s essay Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System to remind myself to be specific, not feel terrible that I can’t ‘change the world.’ And there are many scales at which to do that, each with varying degrees of difficulty. Not all these impulses can (or should) pour into one’s art, but they can in one’s life. The connections between—and advocacy for—mental paradigm shifts towards ecological equity and climate justice are deeply intertwined and require sure voices that are well-informed and deeply inspired.

Suggested Readings

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement: climate change and the unthinkable. The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Experimental Futures). Duke University Press, 2016.

Hofstadter, Douglas. “Analogy as the Core of Cognition.” Lecture, Stanford University, Stanford, California. September 10, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8m7lFQ3njk.

Helguera, Pablo. Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York, NY: Jorge Pinto Books, 2011.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. “Enter the Anthropocene—Age of Man.” National Geographic Magazine, March 2011.

Age of men.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Latour,Bruno, and Catherine Porter. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Polity Press, 2017.

Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press, 2012.