Issue 1

The New Infrastructure of Inequality

You can’t fight injustice if you can’t see it. In today’s digital world, social, economic, and racial injustice is hidden in new ways, shrouded in proprietary systems that are protected from scrutiny by being defined as trade secrets.

Whether embedded in the social media post, the resume-sorting software, or the risk assessment tool used in criminal sentencing, the systemic biases and prejudices prevalent in society are of course not new. But the ways in which they are concealed today often are. How do you notice something is wrong if you cannot perceive its effects on your community, your neighbors, or even yourself?

The increasing pervasiveness of data-driven technology in all walks of life means the consequences of this challenge are by no means limited to the digital sphere. In keeping with the grand trajectory of American inequality, the abstraction and personalization powered by these big data systems have enabled the further transformation of our methods of segregation into something more palatable to a liberal society.

Where To Look

The infrastructure most modern communication and commerce rely on tends to be opaque and beyond scrutiny. At this point in time, access to its inner workings is usually restricted to large companies and private governing bodies whose interests are often unaligned with large parts of their customer base and the general public. Additionally, these systems are usually designed in ways that subvert existing regulations. Measuring the ways in which people are being harmed by them can be challenging, as our methods of accountability have not kept up with the rapid pace at which technology is being developed. Thus, much criticism of the technology industry tends to be hypothetical or speculative.

And increasingly, the methods of personalization that have transformed how we use the internet are also obfuscating the disparate impact that takes place there. Today’s unfettered streamlining of the individual online experience complicates the task of peering into the structures governing it, no matter how monolithic those may be. These realities make it significantly harder for those interested in regulation to collect the evidence necessary to hold tech companies accountable.

With transparency so direly lacking, one useful approach that emerges towards collecting such information is that of harnessing the network and communications infrastructure that the internet is made up of. The data traveling through these systems tell compelling stories, if one knows how to look for them.

Infrastructure

What is the infrastructure that supports modern society, and underpins the way we move in it? The term usually brings to mind bridges, roads, and electrical grids.

Due in large part to its rather abstract nature, it is easy to overlook the fact that our ability to be online all the time is dependent on massive institutional undertakings such as the laying of submarine fiber-optic cables and global dispersion of cell phone towers.

And indeed, access to communications infrastructure has many parallels to that of transportation or water: Studies have shown access to the internet provides significant benefits for low- and middle-income communities in areas such as education, employment, and health.

But physical aspects are only part of the story. Once the fundamental requisite of access has been answered, one encounters a new level of infrastructure—that of online platforms. And here, too, the biases of the creators of these platforms either intentionally or inadvertently influence who it works best for.

We tend to think of platforms such as Facebook and Amazon as socially objective: Anybody can join, all are equal, and the general ethos of Silicon Valley is usually portrayed as progressive, forward-thinking, and working for the greater good. It is exactly for these reasons that the context of infrastructure may be useful for a more critical consideration of the impact these companies have.

To look at systemic racism disguised as a course of action taken for the greater good, let us start with an example taken from traditional infrastructure.

Rondo

The map above is of the center of St. Paul, Minnesota. It was created by sociologist Dr. Calvin Schmid in 1935 as a part of an effort to gather and analyze data on population trends and housing in the city, and was highlighted in the Met Council’s 2016 Choice, Place and Opportunity report detailing racial inequality in the twin cities, and also mentioned in this talk by Anil Dash. The report shows the devastating impact upon immigrant and Black communities of the large-scale public investments that transformed the area’s geography during the 50s and 60s. The case of the old neighborhood of Rondo (on the map’s center left) is a striking example of how an infrastructure project outwardly described as aimed for the benefit of the wider public ravaged a marginalized community.

As Rondo Avenue, Inc. states on their website:

In the 1930s, Rondo Avenue was at the heart of Saint Paul, MN’s largest Black neighborhood. African-Americans whose families had lived in Minnesota for decades and others who were just arriving from the South made up a vibrant, vital community that was in many ways independent of the white society around it. The construction of I-94 in the 1960s shattered this tight-knit community, displaced thousands of African-Americans into a racially segregated city and a discriminatory housing market, and erased a now-legendary neighborhood.

If one overlays the present day map onto Dr. Schmid’s, one can see how the I-94 cuts straight through it.

The story of Rondo is just one from a common trope of the middle of the 20th century where the building of highways was used to destroy African-American neighborhoods.

This practice is but one example of how infrastructure projects have had a severely negative impact on the upward social mobility of African-Americans and other marginalized communities—who of course were not partners in the planning process. While these historical practices of systemic racism are well documented, have we really moved beyond them in the 21st century? History teaches us that new types of infrastructure, while inviting new possibilities for development, also present new avenues for disempowerment.

The lack of transparency that has come to define the infrastructure of our modern networked society (as well as the widespread mystification it instills upon its ostensibly captive users) makes it all the more imperative we be on guard against the likely possibility that similar practices might be taking place upon the highways and byways of our internet traffic.

Enlisting the Browser

This is the context of an investigation we carried out while I was at ProPublica, a non-profit journalism website that focuses on stories that serve the public interest. The central investigative tool we used was a piece of software that anyone who has used the internet will be familiar with—the web browser.

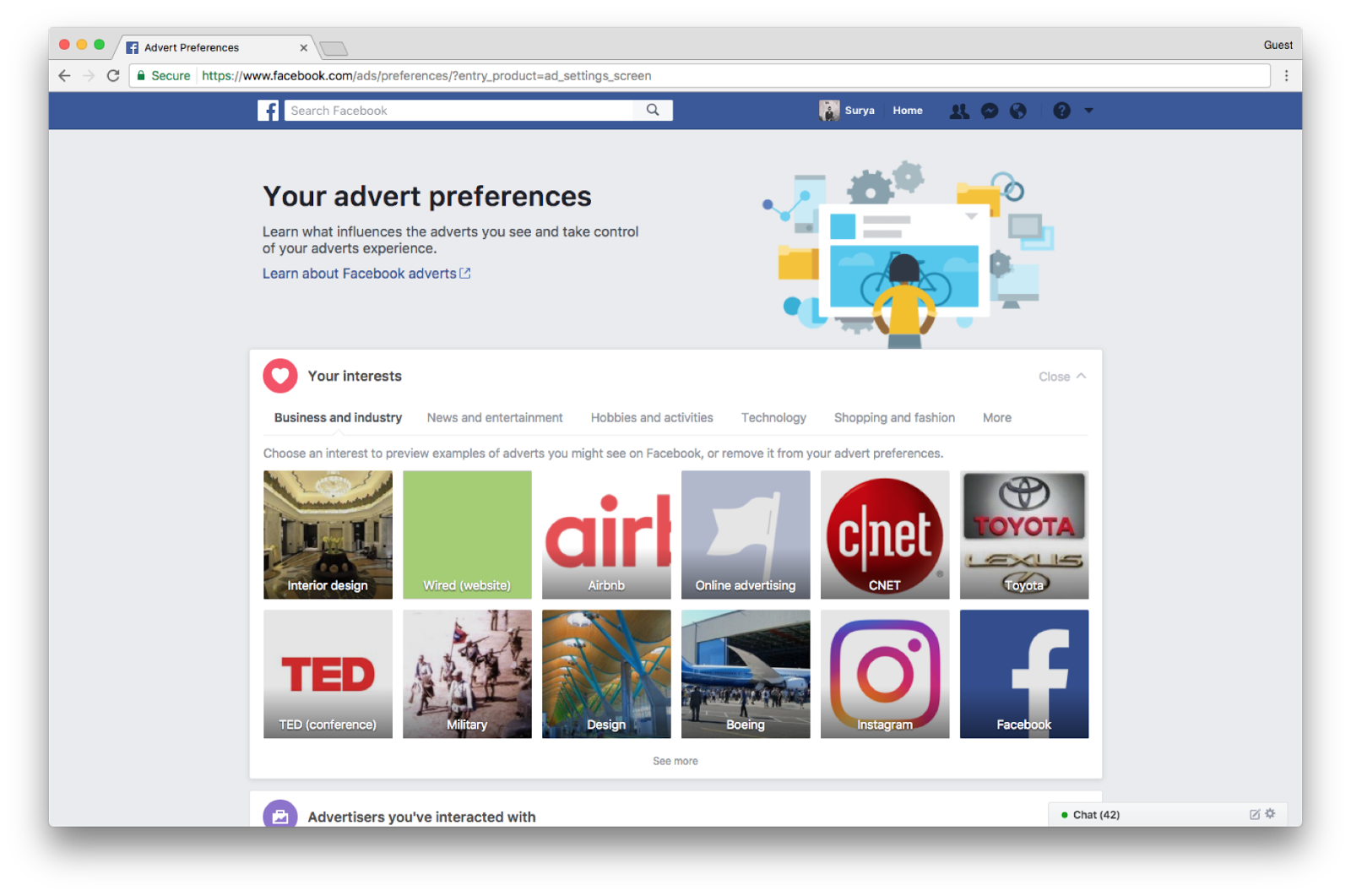

We were interested in understanding how Facebook targets ads to its users, and more specifically, we sought to decipher the difference between how the company was presenting ads to its users and how it was presenting its advertising capacities to parties interested in paying for ads.

We knew there was a difference, because Facebook buys user data from third-party brokers—data which has nothing to do with how these individuals use Facebook, and which Facebook is under no obligation to share with their users due to existing agreements with these third-party companies. But we sought to understand what they did display to users, and how they did so. Collecting the ad categories from Facebook’s Ad Portal was relatively easy. Using the excellent web developer tools that come with modern browsers and a python script, we were able to collect around 29,000 unique categories in which Facebook places its users.

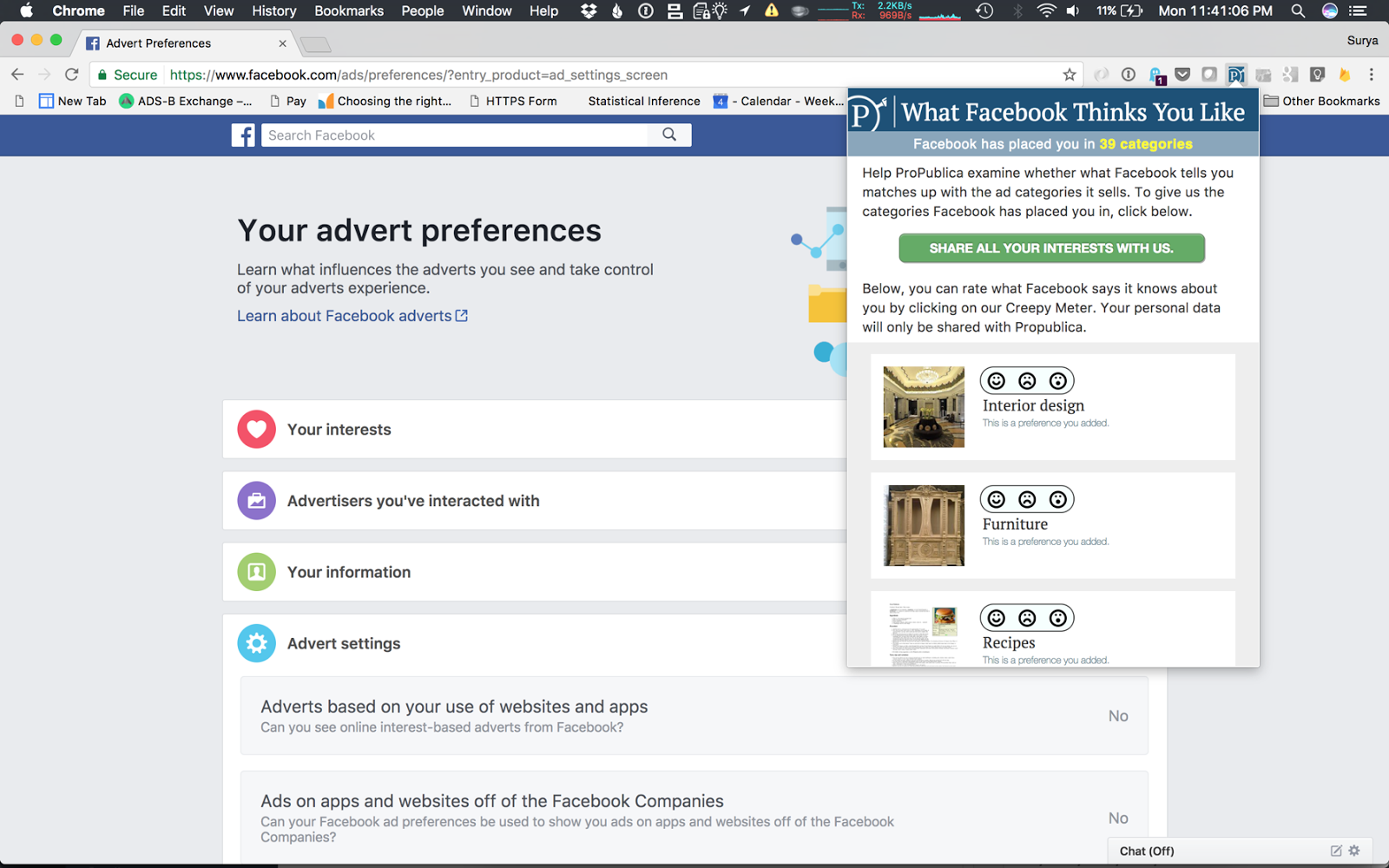

Determining what categories individuals were told they are bucketed in was a more interesting challenge. Facebook lets users see what categories they think they’re interested in by going to the ad preferences in the settings menu. While it’s easy to see the categories Facebook is targeting to a single individual, there isn’t an easy way to get the entire database of categories they have created. In order to get around this, we decided to try to crowdsource their database. We created a Chrome extension that navigates a user to the ad preferences page and, once there, allowed them to share this information with ProPublica. Approximately 20,000 people downloaded the Chrome extension, and we collected around 57,000 ad categories in this way.

After we reviewed these two different datasets, one difference became very clear. Third-party brokers collect data about us from offline sources—a practice users are not informed about. For example, on the Ad Portal, the category “Soccer Moms” is described as a “Partner Category based on information provided by Oracle Data Cloud. US consumer data on where consumers shop, how they shop, what products and brands they purchase, the publications they read, and their demographic and psychographic attributes.” However, when the same category was seen by users, its description stated “You have this preference because you clicked on an ad related to soccer moms.” While it may be true that someone did indeed click on such an ad, it is not clearly stated where that information was originally collected from. When we asked Facebook about this practice, the company said it does not disclose the use of third-party data on its general page about ad targeting because the data is widely available and was not collected by Facebook. While this is the industry standard way for data brokers to operate, it gives users a false sense of transparency.

In the 57,000 ad categories we crowdsourced, what we weren’t expecting to find was a set of categories titled Ethnic Affinity. Among the subcategories were African-American, Hispanics, and Asians. When we asked Facebook about these categories and about whether they allow advertisers to target people by race, Steve Satterfield, the Privacy and Public Policy manager at Facebook, said that the ‘Ethnic Affinity’ is not the same as race, which Facebook does not ask its members about. Facebook assigns members an ‘Ethnic Affinity’ based on pages and posts they have liked or engaged with on Facebook. He went on to state that “It’s important for advertisers to have the ability to both include and exclude groups as they test how their marketing performs.” For instance, he said, an advertiser “might run one campaign in English that excludes the Hispanic affinity group to see how well the campaign performs against running that ad campaign in Spanish. This is a common practice in the industry.”

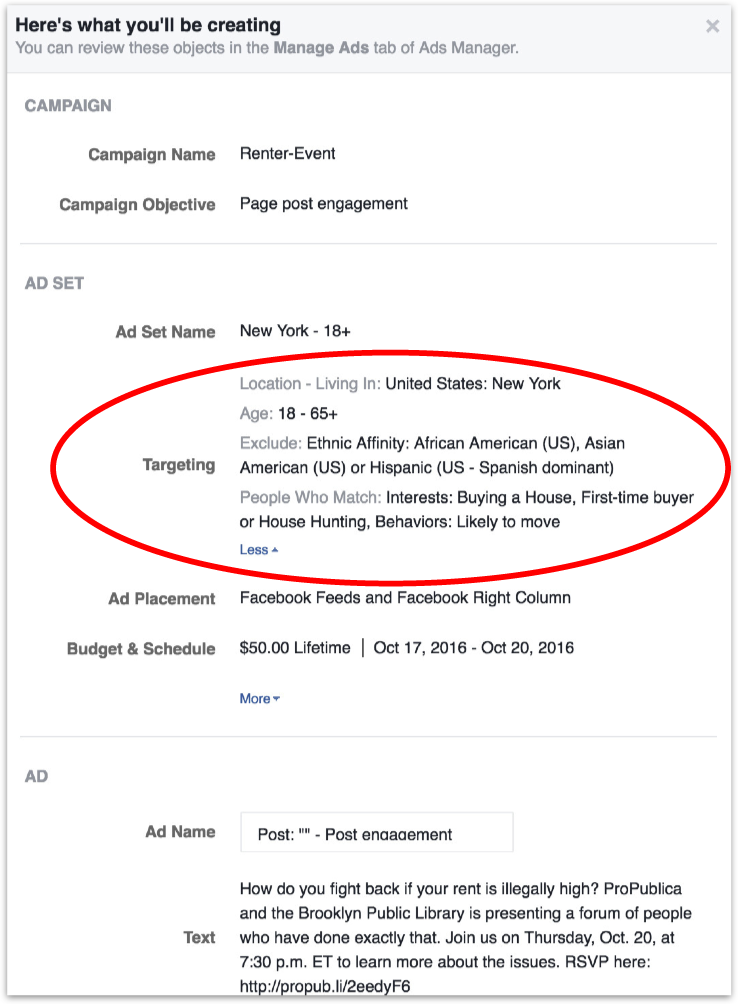

While that seems reasonable, it perfectly highlights the blind spot that exists in the homogenous Silicon Valley idealism, where in spite of all the rhetoric about innovation and disruption, the only metric that really matters on the web (as it always has in print) is how many ads you can sell. The optimization for success in this realm reflects the systemic racism we live with, which echoes the attitudes and methods displayed in the story of Rondo and others like it. For example, Facebook doesn’t have a category for Caucasians. Why should they? There is no economic value in that, as most Caucasian ‘culture’ is just a proxy for what is considered mainstream. If that may seem ignorant but harmless, consider this ad we were able to purchase, and take note of who it ‘excludes:’

The ad is targeting people interested in buying, renting, or financing a house while allowing the purchaser of the ad to explicitly exclude audiences that had an ‘Ethnic Affinity’ with African-Americans, Hispanics, or Asian-Americans. This is in clear violation of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, a law that was enacted to put an end to the malicious practice of redlining. The ad was approved by Facebook admins in approximately fifteen minutes. When asked about this, Facebook responded by saying: “We take a strong stand against advertisers misusing our platform: Our policies prohibit using our targeting options to discriminate, and they require compliance with the law, we take prompt enforcement action when we determine that ads violate our policies.” One problem this response utterly fails to address is that due to the algorithmic practices employed in their interface, one would not be able to exclude Caucasians in the same way.

While Facebook can claim to be engaged with the problem, they won’t be able to solve it without meaningfully engaging with—and considering the needs of—their most marginalized users, especially those whose needs do not align with the demands of the advertisers that the company relies on for revenue. Dismissing such demands as ‘the realities of the marketplace’ echoes, to be sure, the type of apologetics that enabled the devastation of old Rondo.

To consider the importance of addressing this lack of engagement, one needs to look no further than the current hot topic of ‘fake news.’ This buzzword tends to be described as a new problem affecting social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. Yet the danger in this rhetoric is that it tends to treat the problem as a mere glitch rather than a central feature that defines our algorithmic systems, which are designed to do whatever it takes to keep hold of users’ attention.

Until we manage to talk about how to fix the ad revenue model that, among other things, engenders bias in the exploitation of users’ cultural background and the spreading of fake news, the creation and mitigation of such problems will continue to be an endless game of cat and mouse. A game that transposes old forms of control onto these relatively new commons by giving those with wealth and power an easy way to buy and target audiences, and, with the help of features built by some of the brightest minds in Silicon Valley, seamless ways to manipulate them.

We must not allow the policies governing our internet traffic any room to develop in the way our physical highways so often did. We must not allow a situation where, in a few decades’ time, a map of our network infrastructure will reflect injustices done to the communities it cut through.