Issue 1

Reflections On My 100 Days of Making

In David Bayles and Ted Orland’s book Art & Fear the authors cite an experiment that involved giving two groups of aspiring potters lumps of clay. One group was told it would be graded solely on the quantity of pottery it produced, and they would earn an A for 50 pots, a B for 40 pots, and so on. The second group was told they would be judged solely on the quality of their pots, and they needed to produce only one pot – albeit a perfect one – to receive an A in the class.

Over a period of several days, the quantity group was busily churning out pots, and in the process, learning from their mistakes, while the quality group sat theorizing about perfection, frozen in the pressure to deliver a perfect pot. In the end the quality group had little more to show for their efforts than a pile of dead clay, while the quantity group produced a rich assortment of pots of varying degree of perfection, including some very successful ones.

This outcome is not surprising, but it inspired me to think about the way we teach many of our classes at ITP, including my own. I questioned whether the emphasis on final projects and the pressure students put on themselves to create something that is both ‘show’ and portfolio worthy was limiting and not nurturing of our students’ creativity.

In further researching the work habits of creative people I discovered Daily Rituals by Mason Curry, a book that documents the work habits of famous artists, writers and musicians. The patterns revealed in the book were remarkable in their unremarkableness. It was not a strike of lightning or flash of genius that led to inspired and celebrated work. Rather, creative genius seemed to be the result of a talented, motivated person practicing a consistent and rigorous routine of hard work and iteration.

Whether it’s the Beatles, who, as Malcolm Gladwell references in his book Outliers, had played over 1,200 concerts together before they burst on the international scene1; Picasso, who is quoted as saying the key was getting started before he knew exactly what he was doing2; or Hemingway, who woke up early every morning to write and would not get up from his desk until he had written 500 words he was more or less happy with3, the common thread among the creative geniuses I researched was a passion for creating coupled with a commitment to routine and hard work.

Armed with this research and loosely familiar with various 100-day themes prevalent on the internet, I offered a class that challenged the students to undertake their own version of a daily creative practice.

The ground rules were simple:

1. Identify a theme and create a unique and self-contained iteration every day for 100 days

2. Document the effort daily publishing social evidence of it.

100 Days of Making has had two iterations: first in the spring of 2016, and again in the spring of 2017. The class of 18 students met bi-weekly over the course of the 100 Day semester to share our efforts, discuss the habits and work of artists whose practices were defined by iteration—Charles Schulz, Josef Albers, On Kawara, and others—but most importantly we offered each other support through the demanding routine. The participants, myself included, tended to enter the project with high ambitions and confidence but quickly learned that iteration is tedious and difficult. Inevitably, after the first few weeks, enthusiasm wanes. Yet, once past the initial hurdle, most students settled into a habit, spending an hour to ninety minutes each day on their project. Over the subsequent 14 weeks boredom and fatigue were balanced by satisfaction and excitement.

I worked alongside the students sharing the experience with them. For my first 100 Day exercise I chose a project that merged my two professional interests and experiences: architecture and graphic design. In the spring of 2016 I took a photograph every day and produced a graphic interpretation or abstraction from that image. The project consumed most of my free time. My commute to and from work became a search for visual inspiration and my mornings before work were spent manipulating those images in Illustrator.

Favorites from the 2016 collection include a view of New Yorkers marching single file in the snow…

…the pattern of trees in early spring…

…and the subway platform late at night. The practice offered a fresh view of New York City. I was thrilled when spring finally arrived, offering new shadows and fresh light on familiar scenes.

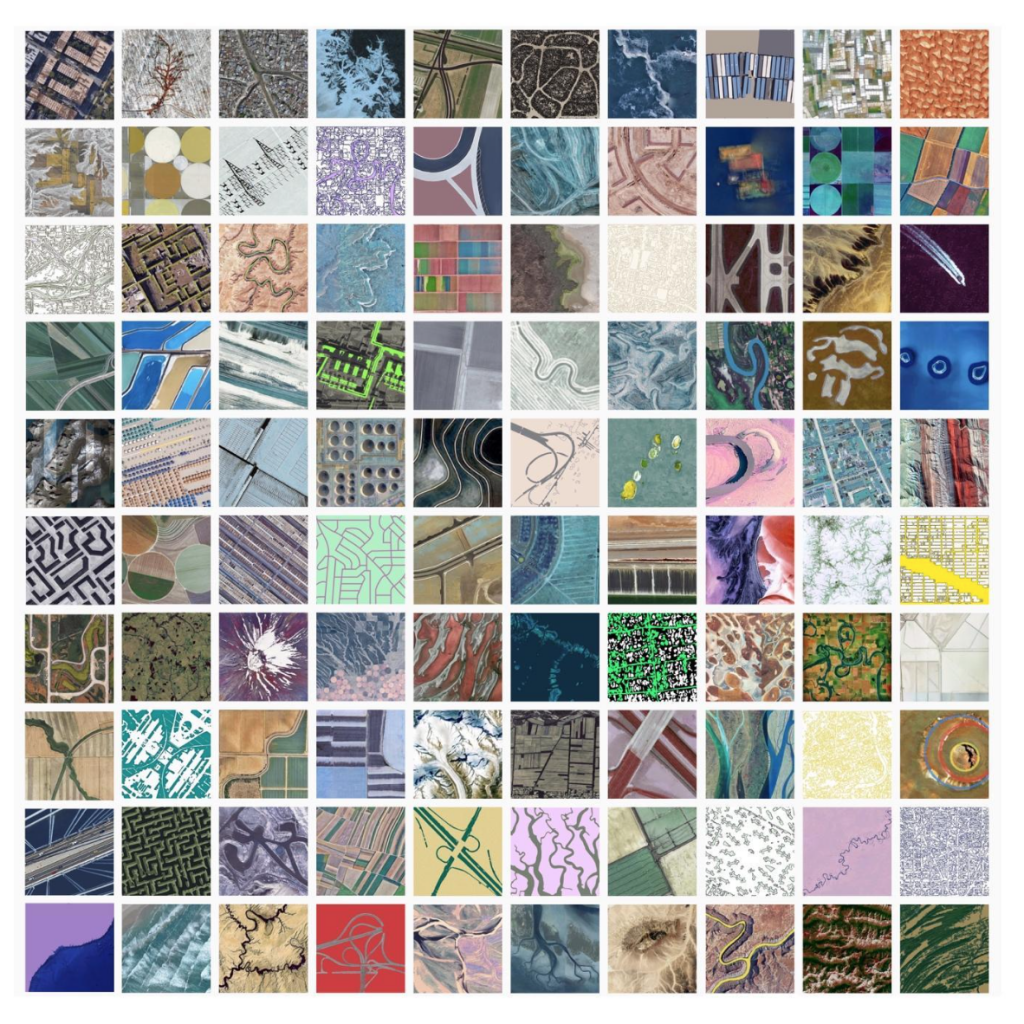

In the spring of 2017 my 100 Day project was a graphic interpretation of an image captured from Google Earth. I spent hours scrolling across the digital globe looking for scenes that revealed unique patterns, unexpected colors, or compelling shapes.

The motion blur of the container ships in the Hong Kong harbor and the path of melting snow in the Swiss Alps provided opportunities for unique compositions.

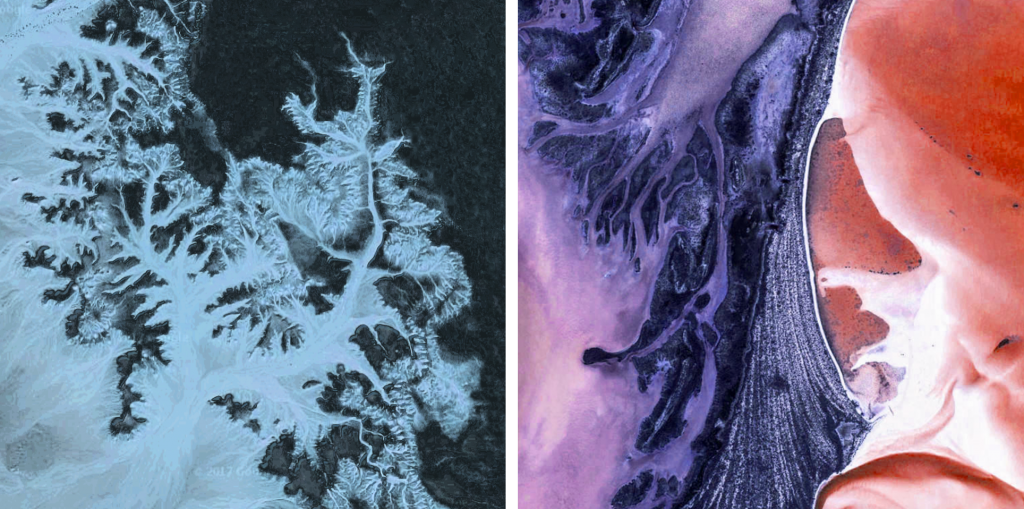

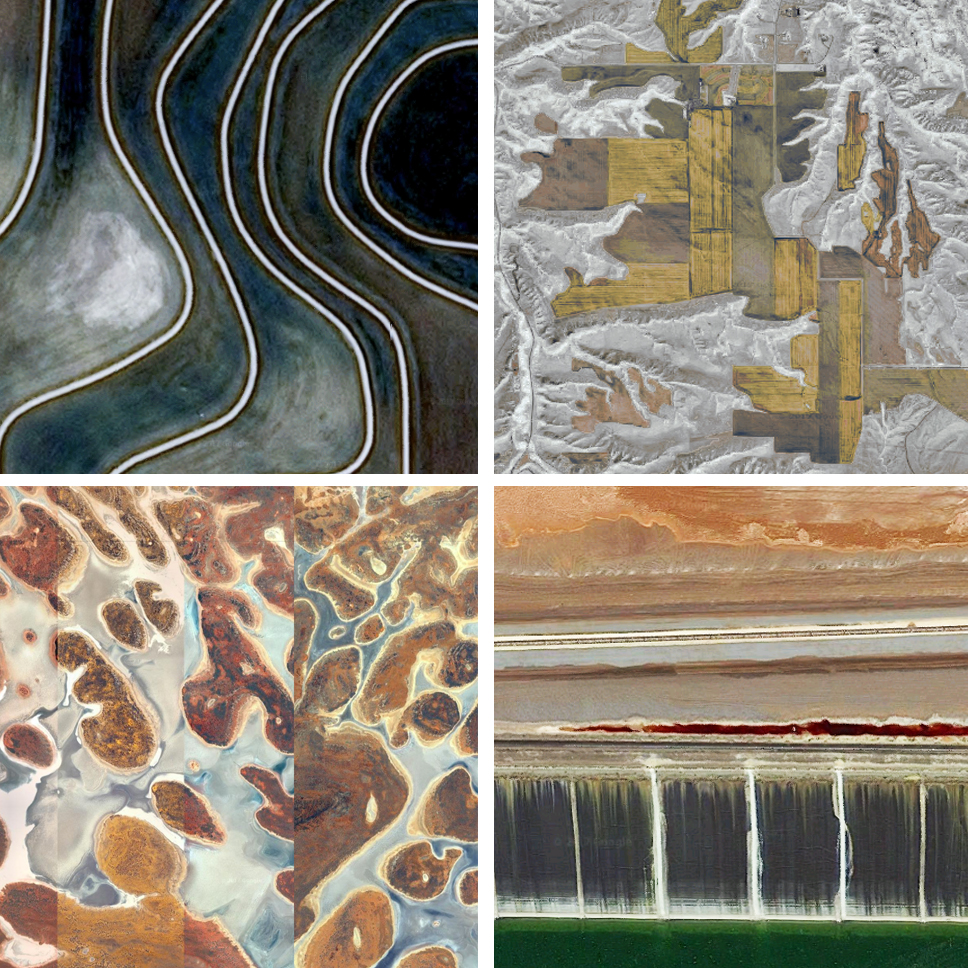

Inverting the color of a scene in Libyan Desert exaggerated the exotic patterns of the sand. Similarly color manipulation of the Bahamian reef reveals exotic water flows.

Each day, I imported into Photoshop or Illustrator a screen capture from my satellite-travels and manipulated the image. The level of intervention varied as the landscapes themselves were often strikingly graphic.

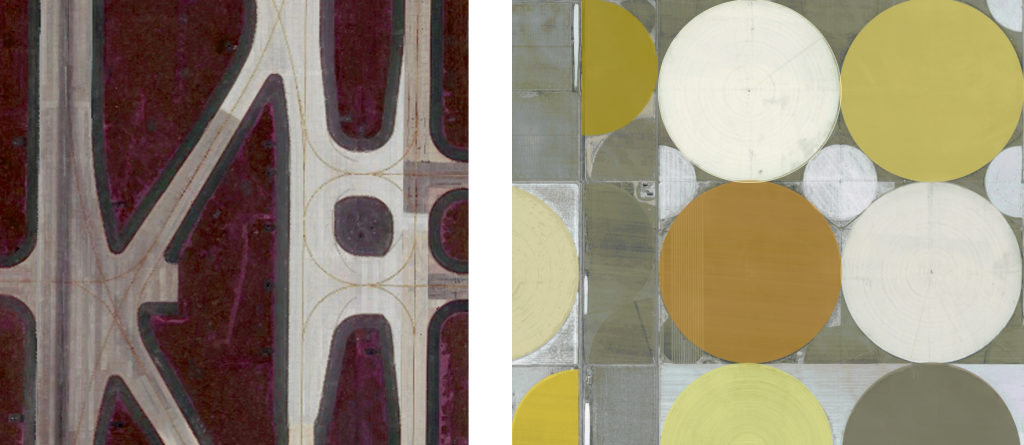

The farmlands of western Montana and runways at Dulles Airport provided graphic compositions that I enhanced with color.

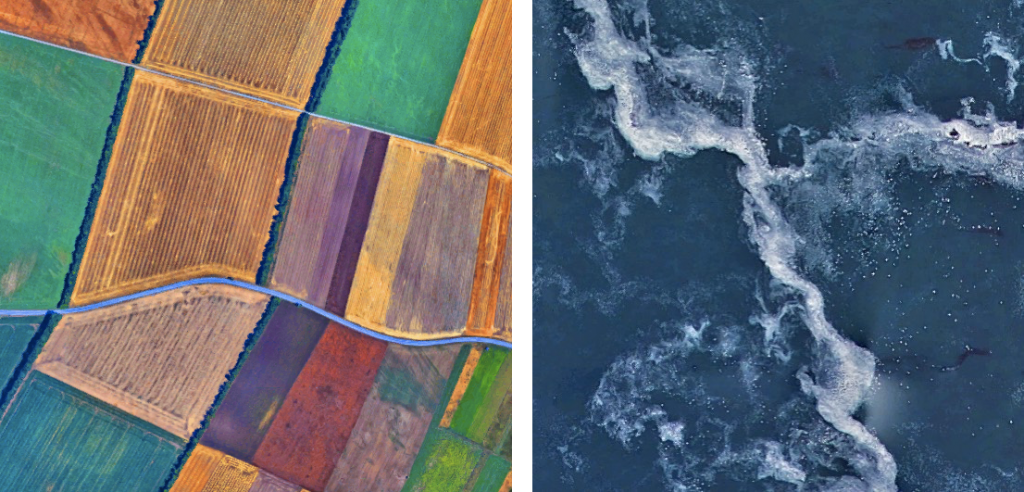

The stillness of the farmland outside Vienna, Austria and the energy of the sea near Monterey, California were opportunities for compositional richness.

Sometimes the natural beauty of a scene overwhelmed me and I did little to modify it, often just enhancing the color to highlight a particular pattern. Other images involved more graphic intervention using color distortion or image editing to create a more compelling abstract composition.

Australia was incredibly rich in possibilities with exotic land and water formations prompting distinct iterations. When taken out of context, the landscape on the bottom right reads like an elevation but is a plan/aerial view.

A 100 Day practice is difficult to maintain but it is exhilarating see a theme evolve and a body of work grow. To me personally the 100 Day experience has been liberating as the pressure to produce exceptional work every day is lifted. There is always a fresh start tomorrow with time for experimenting and space for experimentation and forgiveness. Every new day brings opportunity for a fresh start.

In a few instances I found the glitches in the satellite to be inspiring and chose to exaggerate them.

The result of my 100 Day effort is a series of images that reflect a wonderful, personal journey that I took through my desktop. No one image stands out as exceptional but the collection as a whole is enormously gratifying.

What I have learned in teaching and practicing 100 Days of Making is that when you couple creativity and discipline exceptional work is produced and in the process the maker learns a lot about themselves.

I invite you to follow my 100 Day journey as it continues @DillonKatherine on Instagram