Issue 1

What’s With the Mirrors,

Danny Rozin?

In the early spring and fall of 2017, Adjacent editors Lindsey Piscitell (ITP 2018) and David Lockard (ITP 2017) sat down with Danny to discuss his path from designer to artist to educator, and to see if they could get him to answer that one question on everyone’s mind: What’s the big deal about mirrors, anyway?

This interview has been edited for content and consistency.

Lindsey Piscitell: Tell me about your early career.

Danny Rozin: I worked as an industrial designer for ten years in a big corporation. Being an industrial designer, in the setting that I was, was not a very fulfilling thing for me. We were handed projects very late in the process where engineers had engineered it and marketing people had defined it. We were in charge of the last one millimeter of plastic to make it beautiful or pretty. I didn’t necessarily love that. I also felt a huge frustration always working with engineers to implement my designs. We would create beautiful sketches and designs and then it had to go through the hands of engineers that would make it not so great. I felt like they were always compromising in the wrong places.

That was in Israel. Another thing that I wanted to experiment with was not living there.

Then I was looking for graduate studies, and I found ITP. When I came to ITP, I took physical computing with Dan [O’Sullivan]. At the time, it wasn’t a foundation class.1 It was a second-year advanced thing, because it was just the beginning of physical computing worlds. Then…after graduating…I got an opportunity to stay here. We didn’t have residents yet, but we had research fellows.2 I started doing research.

For me, having learned how to program here [at ITP] and having learned how to do physical computing type stuff and having known already how to do design, these three things came together and suddenly I felt like I wanted to create projects for myself. I didn’t want to work for clients anymore.

Coming to ITP and being able to do the engineering and the design of my things all by myself was a huge revelation. I never wanted for someone else to create any of my art. My art is a very personal thing for me, so I don’t want to be a producer or project manager of my art and have it built by others. I want to touch every last thing.

LP: How much do you think growing up and working in Israel has influenced your work?

DR: [Hesitates]. I’m not sure. I’m not sure. I know for sure that I would not be able to be an artist in Israel. I could never create art under such scrutiny. For me, the open atmosphere at ITP and the possibility to just experiment or to fail was a much, much more fertile ground for me to create art. I needed that complete break from almost everything in my life to reinvent myself. It was at the age of thirty-five or closer to forty when I first thought of myself as an artist, so it really was a kind of reinvention. If it wasn’t for Red Burns3, who created that fellowship and allowed me to be the first one to take it, I would probably not be an artist because I needed that nesting. I needed that no-pressure possibility to think about what I wanted to be for a while.

My first project was called “Easel.” It was this easel made out of wood with a canvas on it, but it was projected from the back and you could paint on it with a brush. What you were painting was live video of yourself. Remember, at the time, we didn’t have iPads, so this idea that you directly apply, like a touch screen—we didn’t have touch screens. I had to invent this whole thing with the brush and the canvas in order to allow painters or designers to paint or design directly on the screen or, in my case, the canvas.

I thought of it as more of an invention thing or a tool for others to use. Then I got an award from Ars Electronica4 that year. That was the first hint that this thing could live in the zone of art.

LP: Before that you had still been thinking of creating tools for other people.

DR: Right. I had some more opportunities to show that piece and a few other pieces that I did, like it. I really enjoyed this idea of painting with video, but it was still the idea…that I was creating a tool and others would be using it. I was still thinking as a designer.

Then there was Ars Electronica. A year later I got to show in SIGGRAPH, which is an organization of programmers and designers and graphic people, not artists necessarily. More and more I got to show these pieces in environments that were real museums or real galleries. Then people were talking about my work as art.

That was hard because I’d always thought of myself as a designer and felt very comfortable with that. Also, being a designer is not as personal, maybe. I do my thing. I create the tool, and someone else does it. As an artist you are exposed.

The next thing that I did was the Wooden Mirror5 and that really took an investment of time. It took me a year to build the Wooden Mirror.

Wooden Mirror (1999) by Daniel Rozin from bitforms gallery on Vimeo.

LP: Would you call that your first intentionally artistic piece?

DR: I think so. It’s hard for me to go back to my mindset at the time, if I was already thinking about it as an art piece. Or maybe I was just thinking about a novelty display or I don’t know what. The university wanted to patent it, which I didn’t want to do. This was an expressive piece, and also the way I framed it, the choice of material, and the way people reacted to it… it definitely became something very personal for me and appeared to be also very personal for people who experienced it. For me, that meant art. Like I said, it took some time until I felt that “that is art and that means that I am an artist.”

LP: Were you surprised by how people reacted to it ?

DR: I was very surprised. I was astonished that it worked. What did I know? I did this thing and I lit it from above and I did like this. [Gestures with hands]. I said, “These are darker, these look brighter. Maybe this needs to be pixeled,” but the whole thing had a huge question mark. I did it after graduation, but my knowledge of physical computing was like a first-year ITP student today. And then you decide that you need to activate 850 motors and connect them to the camera, which at the time was almost impossible technically. It was much more difficult than today to just connect the camera. We didn’t have Processing or anything like that. The technical challenges were such that I wasn’t even sure that it would work. It took many, many months. It really took close to a year to build it, then one afternoon to program it. That’s the ratio between software and hardware difficulty.

Then I was astonished that it worked and that it was so fluid. I imagined that it would be more than creating an image, that it would be an animated thing. I didn’t know that it would be this large thing it turned out to be. I definitely didn’t imagine the sound of it—in a good way. I took a servo motor and I imagined what 835 of those would sound like. I thought it would be a horrible, industrial sound that would be very horrible. The first Wooden Mirror that I built was actually all packed with a lot of foam to try and insulate that sound.

Then the first time I turned it on I was very surprised that when you move in front of the piece, the motors mirror your action just like the visual mirrors. It’s a very gratifying secondary, maybe not even secondary thing because a few months after I created the piece and we hung it, we had a visitor. She was blind, and she really enjoyed interacting with the piece. Of course, for her, the visual part didn’t exist at all. I sometimes do that. I sometimes like standing with my back to the piece and moving so then you only get the sound of it.

LP: It reminds me a little of the old train boards in the stations. I think it’s a really satisfying noise and one that we’re losing now as technology evolves.

DR: Right, for sure. I’m also losing it also with my choice of motors. The new motors that I use now are much more robust but they don’t have the same sound.

LP: Have you thought about simulating the sounds?

DR: For sure. But I wouldn’t simulate it by artificially creating the sound. My wife is a composer and we collaborated once on a project, but it wasn’t a mechanical piece. She composed music for three of my screen-based mirror works. A classical ensemble performed it on stage. We are working now on a piece where a percussionist will perform one of my mechanical pieces. For those, I’m thinking that I could probably trip up or somehow do something to one of these mechanical pieces so it could create more sound than just the motors, so maybe some percussion thing. If I would ever do something like that, it would definitely have to be inherent to the piece, so it would still use the material of the piece.

LP: Have evolving technologies affected your process other than this case of lessening the incidental noise? Have you found it desirable?

DR: Most of them are desirable. It’s becoming really, really easier to do these things, I think for everyone and definitely for me. I’ve become an expert in this particular thing, so moving lots of motors, doing some of the mechanics, doing the vision aspect of it, using microcontrollers and all of that has become something that when I start a new piece, I can pretty much imagine how to create it. The big question mark of will it work—I hardly ever have that anymore. I kind of miss it, but it’s definitely become my comfort zone, in a way.

Also, the tools have really progressed a lot. The Wooden Mirror has been up since 1999, so it’s eighteen years now. Eighteen years ago it was more difficult to get, to program the camera into it, to get the communications working. We didn’t have USB even, then. The whole thing, it always felt like we were sneaking up on tools that were meant for engineers. Also, the internet just started then.

LP: What do you mean by ‘sneaking up on tools meant for engineers’?

DR: The tools that you had to use at that time, you had to read books for engineers, or if you asked a question, it would be to a firm of engineers and they would look down on your ignorance or talk to you in terms that you wouldn’t understand. You always felt like you didn’t really belong.

Nowadays, that’s all pretty much gone, with the whole Maker revolution. We belong. We create our own tools. Tom created Arduino for us.6 These are the tools, and we molded them according to our needs, which is very different than the tools we used before, which always did almost what we wanted, but not exactly, because what engineers want is always slightly different from what you want. Definitely things have become much easier technically.

LP: It seems like you’ve branched out in the medium. Whereas you were only physically building in the past, now some of your work is screen-based, too.

DR: Right, actually from the get-go. This idea of working in software and working physically is something I almost always maintain for my own sanity, because both of them will drive you crazy in one way or the other.

LP: How so?

DR: Hardware is hard. Things break and they don’t work, or if they work they only work for a while. You need to order stuff and it comes after a long time or it gets stuck on the way or it costs a lot of money. There are a lot of difficulties, and you can only do it maybe at ITP or somewhere with a lot of space and tools and all that. It’s wonderful when you’re done.

Software is wonderful in a different way. The flexibility. I know it’s not easy to program, but once you know what you’re doing, supposedly there are no boundaries. You can do whatever you imagine. You have “save as” and “undo.” Physical things don’t have “save as” and “undo.” You start on a particular component and buy a thousand of them.You can’t undo that. In software, if you do something and then at three o’clock in the morning you see that something else interesting has come up, you can just save as and come back to that a day later and that becomes a project.

Also, I tour the world installing my pieces. Every time I install a piece, it’s me shipping a huge crate that weighs about a thousand pounds, and then I show up there and make it work, which is complicated. When I participate in an exhibition about one of my software pieces, I don’t even show up if I don’t need to. I come to sip wine at the opening, like any true artist.

If I do only software, I find that to be a bit frustrating, maybe because I’m a designer also. I like my things to be objects, so even if I do create a piece which is software, I usually won’t just show it on a screen. I feel like I need to do something special. I have pieces that I project on translucent material and sometimes I project on books or weird frames, but somehow I feel like it needs to be special in its packaging.

I have a duality in the way that I feel about technology and showing it. It appears that I love technology because of the way that I use it, but I don’t love to show it. I wouldn’t show a computer. On the other hand, with some of my physical pieces I do choose to show aspects of technology, but usually the mechanical aspects of them. I find that people have an appreciation and some sort of intuition when it comes to technologies that aren’t digital, such as the mechanics of motors, electronics. People have a very hard time appreciating or understanding the craft or skill that goes into software.

LP: Because it hasn’t become something that is accessible or that has been part of our experience for the last 1,500 years? Have we become either so spoiled by how easy technology has become to use that we don’t have an appreciation for how incredibly complex and difficult to execute it—facial recognition on Snapchat, for instance>

DR: Right. You know, I regret that because there is a lot of craft, a lot of skill, and a lot of beauty in these things, but they are very black box-ish or opaque. Here on the floor7, we are equipped better than others to appreciate that. In the real world, people…go to a fair for cars or boats and they want to look under the hood because they appreciate the technology that goes into that, and they can see how it seems well done or beautiful.

Whereas, people go to a movie and see aliens and dinosaurs and whatever fighting with each other and they say, “Oh, this is done by computer,” and that seals the conversation for them. “It was done on the computer.” [Impersonating moviegoer] “I don’t know how they do it on the computer. I don’t know what that means. I can say it. I mark it and then it actually frees me from having to understand it.” Just the fact that it belongs within that black box of wizardry.

I would like to be able to open up that box. Some artists are doing that. Look at Casey Reas’8, early work where he used to actually display pseudo code.

Danny’s Rozin’s “Trash Mirror”

David Lockard: How do people interact with your mirrors?

DR: There’s a pattern that repeats itself. A lot of the time people spend in front of the mirror is an investigation, an exploration. Just figuring out the thing. It really depends on where you see it and how you see it and who you are. A lot of times people will be in front of the piece and not really understand what it’s doing. Then there’s the dynamics of people explaining to one another the technical aspects of it. It’s typically a guy explaining to a woman how it works, and they get it completely wrong. But they are doing it with a lot of confidence. So I like kind of standing incognito and listening to these conversations.

So a lot of the responses that people are making have to do with understanding the piece, exploring the piece, and then performing. Mostly when you see a piece like mine, even though I think of it as a pretty intimate piece, you are in a public space. So when people do funny poses, and jump up and down, they are not only interacting with themselves —they are very aware that they are being viewed by other people. That kind of dynamic for me is interesting.

DL: I wonder if museum guards are often happy to watch over your pieces.

DR: I know they are. I talk to them a lot, because my pieces also have pragmatic issues, like how they shouldn’t be touched. Which is a weird mixed message to give with an interactive piece. It’s wonderful for you to dance up and down in front of it but hey, you can’t touch! So the guards are often the people who feel the brunt of that.

But anyway, often there’s a guard standing many hours in front of the piece, and they learn to love the piece, and they discover little behaviors and they tell me about them.

DL: Openings, especially for your pieces must be difficult because when there’s a lot of people in front of them the mirrors don’t work as well.

DR: Right, right, that’s true. Yeah. And also, you’re always worried whether not it will work. So maybe it’d be nice to have a painting… [laughs] so that you don’t have to worry about whether it will work or not.

LP: So do you have a favorite mirror?

DR: Well, you know, when they’re just born I hate them all. It takes me time to get used to them. Definitely the Wooden Mirror is one that I love and I get to live with because it’s here at ITP, and it’s definitely the one that got me to a lot of places as an artist. It opened doors for me, so that would definitely be one.

I have another piece called Trash Mirror9, which I also like. It’s really personal because it’s made out of my own trash. Some of my other pieces seem to be very repeatable. They’re on a grid. For some people it’s hard to understand what’s personal about it. The trash one—it’s messy and it’s made out of my trash—is definitely a personal piece of mine.

“Trash Mirror” detail

LP: What’s the weirdest material you’ve used (that’s not trash)?

DR: I guess my latest pieces are the weirdest, the ones that are made out of plush penguins or the furry pompoms, and I made one out of these trolls. These are definitely, I think, the funkiest.

LP: What made you go in that direction?

DR: I really wanted to do work with soft materials. I’m just starting that. I hope to go deeper into it, but it’s difficult. Being obsessive about something like I am about this particular combination of these physical, mechanical display mirrors allows me to germinate ideas for a year, five years, a decade, or forever. A lot of the pieces are on the back burner for five years before I actually create them. Usually if I have an opportunity to have a solo show, then I will develop new pieces. Then I would almost select from a few that have been in my mind for a while. They really take a long time.

Doing something with fabric or with fur was on my mind for really ten years at least. I couldn’t figure out how to do it because the combination of soft material or fur with mechanics is really very difficult because they don’t work well together. The pompoms solved it when I had this epiphany that I could use them because they squish. They could squeeze by one another. I could conceive how it could solve that particular conundrum. Then I created that piece.

DL: The troll mirror makes me laugh, and I’m sure delights most audiences. Can you talk about the role humor plays in your art?

DR: The wooden mirror, which was my first mechanical piece doesn’t necessarily have humor – it’s actually finished in a way that’s trying to appear distinguished or respectful – but it evokes joy. And I think joy is a very close to humor. With humor, you are trying to create very explicitly a sense of joy, or laughter. But there’s something about the interaction of all of my pieces that I think evokes joy. In a way, maybe that’s not explicit. When I see people interacting with my pieces, they often seem to be enjoying themselves. And that’s something that’s important to me. I want my art to be accessible and beautiful, and maybe it’s because of my background as a designer – It’s important for me that people enjoy their time with it.

Beyond me liking to evoke joy, I think it’s a very effective tool. For people to maybe actually get into my mindset a little bit, they need to spend some time with the pieces. So I employ different tools. The first tool is that the pieces are pretty. That’s the first anchor. The next one is that the pieces are dynamic, kinetic. They change. That drags you in. And the third is that the pieces are interactive. You move, and the pieces respond to you, and that grabs you some more. The last is that the piece is a mirror. So you see yourself reflected in the mirror, and you get a sense of ownership over the piece…

So maybe by that time you’ve spent 20 or 30 seconds in front of the piece. And maybe at this point, after trying to figure out what the piece is, what it does – and for some, trying to understand how it does it– maybe then you go to the last piece which is the ‘why’. Why does this thing exist, beyond understanding all the tech stuff. But my hope is that even if people don’t contemplate the piece, they’ve still had a good time with it.

DL: Kinetic art is a genre which is often neglected. It’s left out of the cannon for different reasons, but I feel like one of them is that this ‘welcoming’ – that you talk about as a good thing – makes people consider it more of a spectacle, and less ‘deep.’

DR: That’s true. And that definitely plagues not only kinetic art, but also technology art. It plagued video art for many years, because of the novelty of the platform, but I think now we may be over that. Now we’re 104 years into kinetic sculpture, as Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel is often considered the first piece of kinetic art.

DL: And do you feel comfortable being considered a kinetic artist?

DR: Yes, I love it. I like wearing many hats. You know, many of the shows that I participate in are technology shows. They will have the term ‘digital’ in their title, or something like that. And you know, I love the tools of technology, that’s my chosen platform. But I don’t identify as deeply with that as I do being an artist. I’m much happier when I am called to participate in a show about portraiture, for example. Or even about optical illusions, or kineticism. These are perhaps things that have to do more with the essence of what I do, rather than with the vessel, or the tools.

Tech and digital is really a double-edged sword. It has this cool element, especially for young people who think it’s cool. On the other hand, you have the opposite reaction from people who are my age, who are often afraid of new technology and reluctant to participate. But also, I think, for the art establishment, it is not a tool that they can easily ignore in order to see the work for what it is. Technological art will always be looked at through the filter of being technological. It’s very hard for the establishment to not think about that.

DL: I wonder if you could tell me about some kinetic artists who are important to you.

DR: An artist I really love is Arthur Ganson. He creates little kinetic sculptures that really celebrate motion. He creates everything from wires to the gears to the cogs in his sculptures. And a lot of his pieces have a sense of humor. Like, he takes the wishbone from a chicken, and he has a piece that makes it walk. Stuff like that that just really celebrates motion.

DL: This makes me ask – you are so deeply invested in movement – but in movement of inanimate objects. You are not a choreographer of dancers, you are more a choreographer of objects. And it’s an unusual role. How did you find yourself in it?

DR: Well, maybe with my new piece a little bit more, but for the most part I don’t feel like I’m a choreographer of objects. I feel like I’m more a facilitator of motion. My pieces don’t exist without a person. My wooden mirror is just an assembly of wood on the wall, until a person comes in front of it and takes over. So for me, the creation of the wooden mirror never ends; a new collaboration happens every time a person stands in front of it. I see it as kind of a shared ownership. I create some sort of premise and the viewer-participant completes the piece.

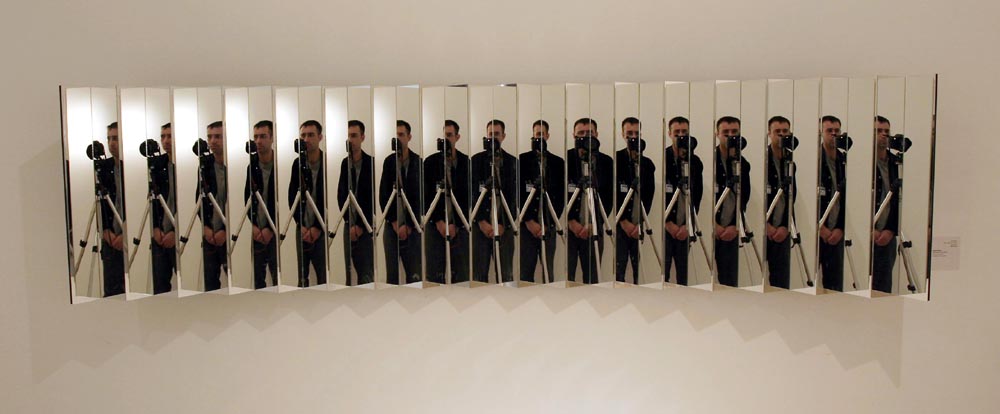

The artist at work with his newest piece.

[Pause]. Choreography might be like that. But with a choreographer, or a musical composer they suggest music and then there are performers, or a conductor interprets it. I don’t think I suggest. I create a tool. A tool is maybe the best paradigm here. You know, a hammer or a plier or a screwdriver – or if you think more artistically a paintbrush or a chisel – are amazing things; without them we would not be able to create art. But they themselves are not the art piece. I’m not saying that my pieces are tools, but rather that without the person they are just the potential for art.

DL: So maybe it would be better to say you are a choreographer of people through objects.

DR: I think so. I think so. Or I’m a choreographer of objects through other people. [Laughs].

And you know, my new piece actually changes a lot of that. It’s not a mirror. Rather it responds to a person’s motion within a series of pre-defined animation sequences. So, in this case the content is the effects that it creates. I have to compose content for it, and that’s a first for me. It’s not very personal or complex content, but it is content. And the viewers participate much less than in my other works. Viewers are lending us their presence, versus lending us their likeness. Much less of an investment on their part.

LP: Do you have mirrors in your house?

DR: They come to my house to die. The way it works is when I show my work through a gallery, it’s a commercial gallery, so pieces that I show are expected to sell. But I never sell the prototype or the artist’s proof. The first piece that I create is when I invent it and I just try to… it’s a bit like an ITP project. I just want to make it work. It’s usually not a very good one. It’s very prototype-ish. Then if someone buys one of the pieces, I will never sell them that artist proof, which I get to keep. I will completely re-engineer the piece so it’s robust and maintainable and all that.

LP: How long does that take?

DR: About six months usually. The artist’s proofs are the ones that I’m left with and those are the ones that I send to museums or these non-profit shows. Then after a while, because they’re not that great, if they die I take them and I hang them at home. I have a New York apartment, so it’s not like there’s a lot of room. The pieces are big, but I have a couple of them at home.

LP: What’s your relationship with regular mirrors?

DR: I hate them. I hate them.

LP: Why?

DR: Because what you see in the mirror is yourself. I’m aging. I’m balding. I wake up in the morning and I see myself when I shave or when I brush my teeth. It’s not necessarily a great experience. I think a lot of people have a very complicated relationship with their likeness. The mirror, it doesn’t lie. Maybe it does, but people in our century have developed all sorts of disorders that come from that very precise ability for them to see exactly what they look like, which is new. The glass mirror is something that wasn’t around until the beginning of the twentieth century.10 Before that, only royalty had mirrors, and even those, they were crappy. They were like polished brass or like looking into a pond, so that kind of reflection. But not the one that you can see all your wrinkles or all your blemishes or compare yourself one-to-one, like I look like this and the other people look like that and how does that compare?

This huge amount of detail and precision that we get from a real mirror is, for me, problematic. I think one of the reasons that people enjoy interacting with my pieces is that they are abstract for the most part, even the software ones. It frees them. Most of my pieces are shown in public, so it’s not like you’re alone. You might be alone in the room, but some other people could be with you in a gallery. It’s a combination of an intimate thing and a very public thing.

Also, there is the idea of surveillance. If I grab your image with a camera, even though I would show it back to you, you perhaps wouldn’t feel easy about technology capturing your image like that. But because of the high level of abstraction … I like to think that my pieces capture and display your soul versus your details. I think the real mirrors show you all the details, and I try not to show the details but to reflect the essence.

LP: So, Danny, is that the reason you’re obsessed with mirrors?

DR: The mirror, for me, is a very convenient platform for my art because there are two things that I really want to do. One of them is I’m really curious about creating images. How do we create images? What constitutes and image? How do we perceive images?

The other one is the idea of participation and interaction. A mirror is a very, very useful platform for such experiments, because when you stand in front of one of my pieces, hopefully after a few seconds you understand immediately that it’s you. Then you stop thinking about the content of the piece, because you understand that the content of the piece is you. You understand that the thing that is probably more interesting for me as an artist, and is what this piece is about, is the form of it. When there is content or text or anything, people read so deeply into it, they sometimes neglect to think about anything else. When you understand that you’re the content, that takes it out of the equation or the conversation and you understand that the things that are important here are mechanics, the concept, the materials, all the other stuff. Because of that, it’s such an interesting platform for me.

The other thing, of course, what I said before.The mirror is a magical, magical invention. We don’t talk about it as an invention, but it is an invention. It’s a profound invention. Can you imagine going through life not knowing exactly what you look like? It’s amazing. I know that I’ve been exposed, like all of us, to mirrors and to pictures of myself from a young age, so you grow up with it, but still the discrepancy or the friction or the contrast between the way you think, the way you feel your body from the inside and the way it appears from the outside… they’re two completely different things. The mirror or the camera brings them together. For me, that’s a very interesting contrast, something that I like working around.

I also create sculptures from mirrors.

LP: Is your intention with those sculptures to show somebody a ‘true’ reflection?

DR: A mirror comes with many layers of narcissism and vanity. One of my pieces, called “Self-Centered Mirror”11 takes a certain type of optics, which is called retro-reflectivity, and creates a mirror that, no matter who stands in front of it, the viewer only sees himself and no one else. You can stand with a group of people and each person one will only see themselves. For me, it takes the narcissism to the ultimate, to the next step–and shows the absurdity of the mirror.

Danny Rozin’s “Self-Centered Mirror”

LP: How much do your mirrors cost to build?

DR: It depends on the model or whatever, but the physical pieces cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

LP: The mirror outside?12

DR: The mirror outside was rebuilt once about five years ago when all the servo motors were replaced with stepper motors. That was the very, very hardest thing because when I created the piece, I was thinking like an ITP student, so I had 835 servo motors glued with hot glue, and never thought that the thing would work for more than a couple of weeks. Seventeen years later, I had to reengineer it in a way that would be more sustainable.

LP: How many have you built? Do you know?

DR: I’ve built around fifteen types of them. I’ve built over fifty additions and commissions and stuff like that.

LP: Maybe we should wrap up on a light note with something that you said before about this moment at the beginning of every project where you hate it, and this is why artists are depressed people.

DR: [Laughs]. Yes, so why are artists depressed people? The process of creating a piece of art or any project is one of diminishing opportunities. When you start to embark on a piece of art, there’s a universe of possibilities. Is it going to be an installation? Is it going to be a painting? Is it gonna be a sculpture? Who knows! Is it going to be a poem? Everything is possible. Then you narrow it down. You say, “Now it’s going to be a sculpture. It’s going to be a digital sculpture. It’s going to be made out of wood. It’s going to do this. It’s going to do that.” You’re narrowing it, narrowing it, narrowing it, narrowing it. Still, all the time you’re imagining all of the potential that it has because you’re looking for a particular potential, but for the most part you’re imagining that potential.

Then, in my case, there’s one moment when I turn it on and the programming is done and it works. That is the moment where all its potential is collapsed. It doesn’t have the potential to be anything else. It is what it is. All of these different thoughts that I thought when I said, “Will it be pink or will it be green,” and now it’s green and it’s beautifully green, but it’s not that pink and that pink was a potential that it had. It no longer has that potential.

There’s death about it. As wonderful as it is, it signifies also all of the stuff it will never be. At that particular moment, I personally feel that kind of regret for all the other possibilities. After a while, of course, you get used to it. Hopefully since you are the person that took all these decisions and, for the most part, you are okay with all these decisions, you love the piece, but it takes time.

I think all artists probably have that. Like I said, the art of creation—which you think of it as if you are starting from nothing and you’re adding things—it’s actually the act of subtracting. You are starting with a universe of possibility and you are narrowing it down to one specimen of something which, you know, you had to kill a trillion possibilities along the way. That’s a sad thing.

LP: Is there anything that you wanted to add in about your work, or do you think that we’ve properly covered the lifetime of things that you’ve been doing? [Laughs].

DR: [Laughs]. You know, in the beginning of my career, I was more known in the field of interactive media by creating tools, by creating software. Then for some years I created my own art. Maybe I’ll influence the field more than anything as an educator because by now, you could do the math, but thousands of students have gone through ITP, and maybe the biggest way that you influence the world is not by pooping out artifacts every so often, but actually by passing on some knowledge or passion or appreciation or ability to create to other people.