Issue 11: Sweat

THE DIALECTIC OF DOOMSCROLLING

“What will a human being be like who is not concerned with things, but with information, symbols, codes and models? There is one parallel: the first Industrial Revolution.” —Vilém Flusser1

Software ate the world2. We, humans, are in the digestive tract of the global technological-capitalist organism, which Karl Marx identified as the capitalist mode of production and Vilém Flusser calls “the apparatus”. We are being metabolized by it. This is nowhere better reflected than in the form media consumption takes today: “doomscrolling”. This digital phenomenon, beget by the ubiquity of smartphones, is a neologism describing the pathological habit of consuming an infinitely scrolling feed of media content to the point of psychological self-harm. The following analysis will explain how the transition from desktop computer to capacitive touchscreen unlocks an all-new profit model which threatens human dignity and independence. These events are unfolding in a disturbing parallel to those of the First Industrial Revolution. Smartphones and digital platforms are the machines of large-scale industry in the twenty-first century. They bring about the real subsumption of the human spirit within the digital-capitalist mode of production. Its machinations impose a suite of gestures which individuals use to pursue basic social livelihood, but which simultaneously cause mass suffering and exploitation. This revolutionary model transforms a person trapped in its addictive cycle into a living being something more like constant capital than worker.

The Computer

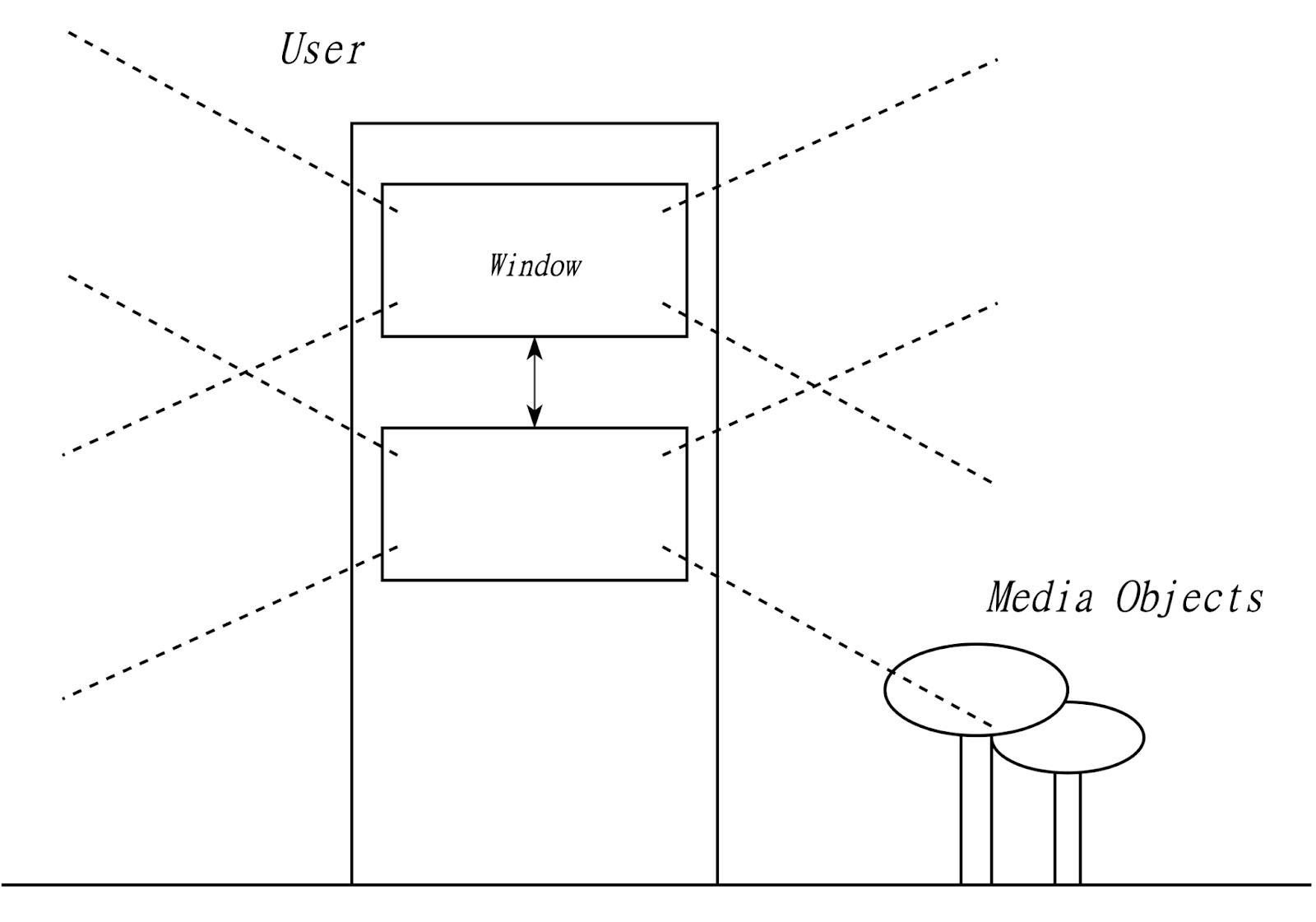

The computer, a stationary work-site consisting of a screen, keyboard, and mouse, is the appendage of the white-collar “digital bourgeois”: the Google employee or Worker’s Compensation adjuster. The screen is an analog for the page, the keyboard a digital typewriter, the mouse a stylus. The operation of such a system is an indirect brain-to-screen interface which requires coordination, skill, and dexterity. The use of the computer is mediated by a complex interplay of keys typed, mouse clicked, and screen read. Young children must be trained to type on the keyboard and many are not very good at it even into adulthood. If for Flusser the typewriter is the machine analog to the piano, the computer might be the analog for the orchestra’s conductor. Computer work is skilled and involves data entry, word processing, information management, logical reasoning, problem solving, programming, designing, innovating, and disrupting. Computer interfaces are made up of windows, entailing sight, visibility, horizontality. Its horizontal orientation is set in the aspect ratio 16:9. One can see through the computer as one can see a landscape through a high window. Its gestures are of freedom, breadth, expansion, perpendicularity, and boundless space. The computer-user takes the position of the capitalist employer, manipulating both animate and inanimate objects in the fine-tuning of profit margins. For Flusser, this is what constitutes a technocracy:

“Technocracy is the form of government of bourgeois ideologues who would turn society into a mass that can be manipulated (into an inanimate object) […] It becomes an objectively perceptible and alterable apparatus, a human being an objectively perceptible and alterable functionary. Through statistics, five-year plans, growth curves, and futurology, society does in fact become an ant colony.”3

But this class, and the computer, is already a living fossil reserved for the high cult of the bourgeois technocrats. Computer laborers infrequently produce value directly; instead, they develop machines, and manipulate the users of those machines as marionettes on strings. It is these machines that we must turn our attention to, for they have superseded the computer’s profit efficiency by a far margin. Their name is the capacitive touchscreen.

The Touchscreen

The capacitive touchscreen is a mystifying veil over the rational kernel of the computer. To touch a touchscreen is an oxymoron: you believe you are tapping a button but you are feeling nothing at all. What is feeling is the screen, abrim with energy and sensors. In fact, the screen touches you. The human body is electrically conductive because we are filled with fluid, and our cells filled with conductive ions. So a layer of conductive material is placed upon a screen, which generates an electrical field. When your finger approaches, this electrical field is drawn upward to touch your own. The screen’s highly sensitive capacitors read this disruption in its own field: capacitive coupling4. The device’s processor analyzes the location of your gesture on the screen. It then decides how to react to you.

Touchscreens proliferated with the introduction of the Apple iPhone in 2007. The iPhone revolutionized the technology industry and subsequently the world, as Marx predicted5. People now spend more time than they ever have before engaging in labor and economic exchange through smartphone apps. Such apps are designed to supercharge any person’s ability to participate in the economy, operate as a small business, purchase and sell commodities, or labor to produce data, content, and attention. This quantitative leap causes qualitative transformations in the social fabric, dialectically rippling outwards from Silicon Valley to the far reaches of wireless networks. The smartphone reorganizes social relations, disrupts and re-creates new modes of production, and exploits and dehumanizes “users” across the globe, corralling them into clusters of data and A/B testing groups. Flusser says it best: “the hands have become redundant and can atrophy. This is not true, however, of the fingertips. On the contrary: They have become the most important organs of the body”6. The body has been outmoded; only a man’s electronically capacitive, digitally capturable activities are of any worth.

The Doomscroll

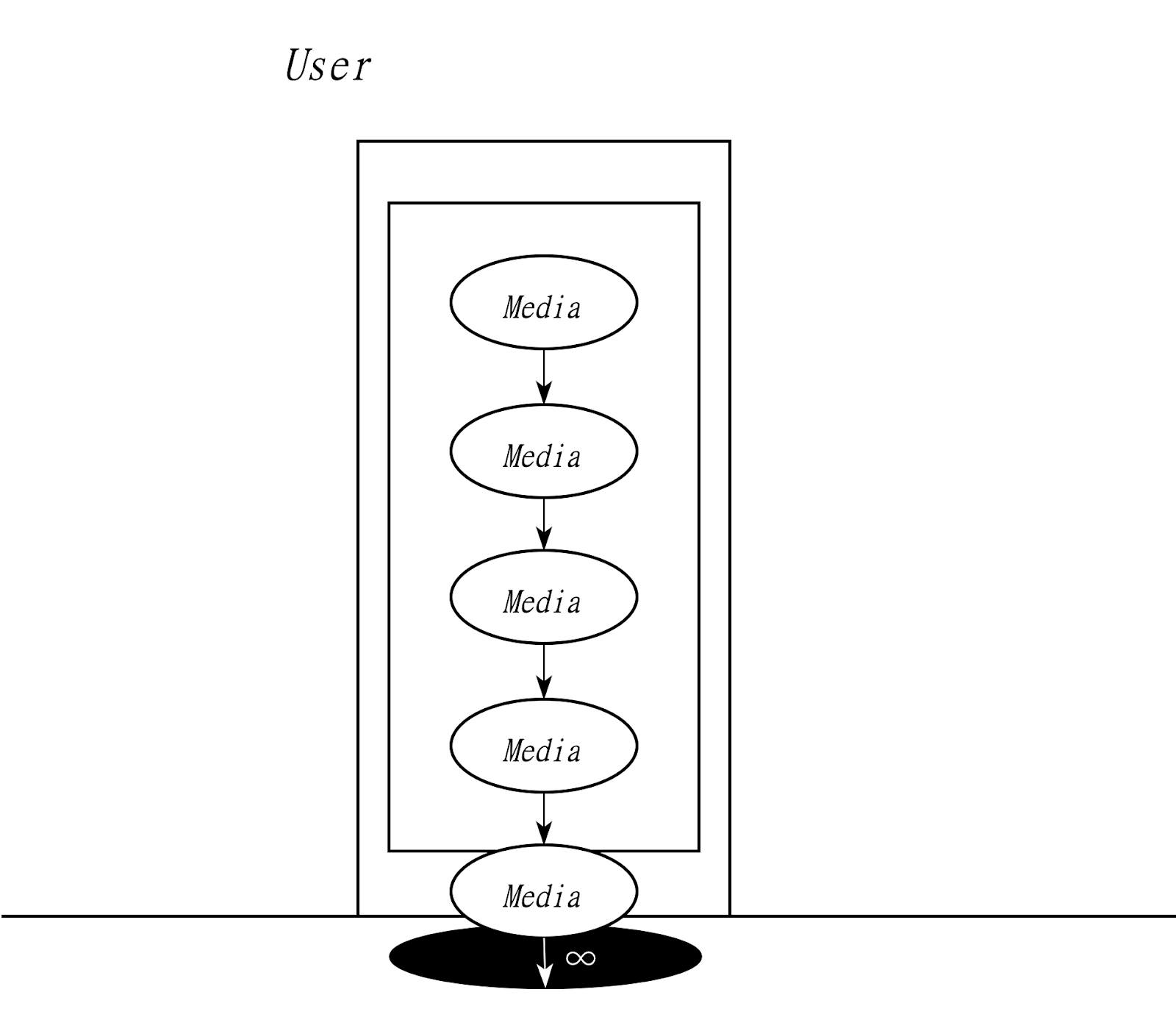

The way smartphones are used today is opposite in character to classical computing. The smartphone is vertically oriented rather than horizontal. Its aspect ratio is 9:16, and displays vertical photos and vertical videos. The person who touches its screen is hemmed into a narrow corridor in which they consume, or are fed, from a “feed” of media content. They move around by swiping (horizontal, limited) and scrolling (vertical, infinite). A scroll can only reveal information in small snapshots as it is progressively unrolled at one end and re-rolled at the other—tunnel vision. One traverses this scroll in a downwards direction of potentially great but unknowable depth: a rabbit hole. The rabbit hole is booby trapped. This vertical orientation is a limited space, confined, with no room for free articulation and only the ability to repeat over and over what came before—that is, going further down. It is narrowing and parallel to many others doing the same but never intersecting. When one finally “returns to the top” for air, it is with great force and rapidity, so fast they might experience whiplash. Confused and bewildered, they are free to go find another hole.

This is the gestural affect of “doomscrolling”, a neologism of the 2020s which describes the qualitative shift toward addictive and seemingly endless media consumption on technology platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. The infinitely scrolling content feed is the present apotheosis of mass media and the site of the vast majority of digital communications and information exchange. It is the next phase of real subsumption of what Tiziana Terranova described as “free immaterial labor” in 2000. It is evident now that the tech industry has unlocked the correct “virtual machinery” to enable the production of infinite relative surplus value. This machinery is based on vast data collection and machine learning algorithms. It works based on turning a relatively small percent of users into “small masters”7 who produce content successfully, with a very small shot at making a living. It entraps the totality, themselves included, in a vicious cycle of addictive consumption. The moral corruption of these algorithms are plain for everyone to see. Venture capitalists are eager to share their strategies, which they call engagement, stickiness, and retention8, words which reference the “dark patterns” of enticement, capture, and imprisonment of users’ attention and life-force.

The conditions of the immaterial laborer are the opposite of the material laborer of the First Industrial Revolution. Where the factory worker of yore worked ten back-breaking hours in the factory before returning to his cot, our immaterial laborer is as materially comfortable as they could possibly be. Their life is resplendent with commodities, foodstuffs, and free time (relatively). So what’s the problem? The problem is that content consumption, understood as immaterial labor, expands the working day to 24 hours. The immaterial laborer has their mind and thumbs put to work as long as they are not sleeping. The damages to their person by this are largely psychological, rather than physical. As such, they result in a degradation of a different sort. First, infinite availability of media to consume cognitively dulls the user and activates regions of the brain that are associated with drug addiction9. This has resulted in measurable imbalances and dysfunction of the neurotransmitters of the brain, impacting dopaminergic and serotonergic balance. People engage with their smartphone as shift work from the moment they wake up to the second they fall asleep, on and off, disallowing the full resumption of restorative activities10. All the deleterious effects of this are externalized to other parts of human life—to the management of their psychiatric symptoms by the pharmaceutical industry, their suffering and isolation, their executive dysfunction, so long as they continue tapping and swiping.

It is clearly evident that smartphones and their social applications, in the hands of manipulative capitalists and their relentless pursuit for profit, diminishes the human brain and spirit. The experience under this tyranny is so unpleasant that its nature has entered common parlance as “doom”. It is a wonder there is no great struggle over its abolition, only more fervent uptake of its enmities. This fact alone speaks for the power of the psychosocial trance it holds society in. The most concerning question is that of future generations. Because immaterial labor is not widely considered to be labor, technology companies are free to infinitely exploit children. Marx wrote on child labor: “Now the capitalist buys children and young persons. Previously the worker sold his own labour-power, which he disposed of as a free agent, formally speaking. Now he sells wife and child”11. Child and adult alike are subject to the machinations of the platform machinery. This is made all the more poignant by the fact that touchscreen devices are being used to distract and babysit infants and children by parents who, in turn, distract themselves from the demands of adult life with the very same devices. Into the jaws of doom they all go.

Users Become Machines

Does an individual’s freely given time and attention truly count as “free labor” as Tiziana Terranova suggested in 2000? Alternatively, we might look toward Christian Fuchs’ “prosumer”12 (a dual producer-consumer) model, which adopts Dallas Smythe’s concept of the “audience commodity” in order to position such “free time” as “surplus labor time”. Gesturally, however, this supposed “immaterial labor” does not smell like work. In fact, it feels more like play. How can this be? In his analysis of the rate and mass of surplus-value, Marx remarks on capital’s tendency to “reduce as much as possible the number of workers employed, i.e. the amount of its variable component, the part which is changed into labour-power”13. This doesn’t line up with the greedy user-capturing platform capitalist, although we can easily counter with the fact that since their labor is free, they can be accumulated with no harm to the rate of profit. However, it might be noted that immaterial activities don’t form any recognizable or politically useful class as Marx’s theory of labor demands, for its members are in fact members of every class. An alternative model is clearly needed to grapple with the fundamental changes wrought by consumer information technology typified in the “doomscroll”. Flusser’s essay “Beyond Machines” offers an alternative viewpoint:

“[W]ork in the classical and modern sense is being displaced by functions. One no longer works to realize a value, nor to discredit a reality, but rather functions as the functionary of a function. This absurd gesture cannot be grasped without observing machines, for we are actually functioning as functions of a machine, which functions as the function of a functionary, who in turn functions as the function of an apparatus, which functions as a function of itself.”14

Flusser’s theory posits that work in the present day becomes functional in nature, in other words automatic or tautological: in other words, like a machine. Marx suggests that “a portion of the instruments of labour acquire [a] social character”15. What if the instruments of labor were social organisms themselves—people? Perhaps the real subsumption of a person immersed in a world of capitalist machines is their becoming a machine itself. Through the methods of gamification and strategies of engagement, stickiness, and retention, social network effects, and other entrapment techniques, users can be psychologically groomed into effective value-producing machines. Ever more enthralling notifications and features can be endlessly devised to top up the oil of these organic machines and counteract their “moral depreciation”. Touchscreen laborers become touching machines. They are dispossessed and expropriated from their own minds and bodies. Their alienation is complete in their transformation into an organic machine only useful for its fingertips.

Such a theoretical flip is heretical to classical Marxism. But perhaps the present story begins where Marx’s ends: with the self-destruction of capital by its own reckless consumptive forces, which take up humans as a “free gift,” just as it once took up waterfalls, coal beds, and common lands. Rather than provoking a dramatic revolution, capital has become “disturbingly lively”16, taking on humanlike agency. It becomes embodied in Flusser’s apparatus and transforms humans into “frighteningly inert” organic machines. These organic machines do not labor, but function as the apparatus’ means of production, consuming the chum that infinite-scrolling doom feeds throws into their maw. This freely generates surplus value at a rate of 100% profit to benefit an equally compromised ruling class who act to maintain the machine out of the machine’s own necessity. Flusser understands this, too:

“We have learned that we cannot live without the apparatus or outside the apparatus. Not only does the apparatus provide us with our bodily and “intellectual” means of survival, without which we are lost, because we have forgotten how to live without them, and not only because it protects us from the world it obscures. It is primarily because the apparatus has become the only justification and the only meaning of our lives.”17

The doomscroll is merely an expression of the self-determination of the capitalist apparatus to enrich itself at all costs. The human being is consumed as an industrial byproduct, extracted of its “free gift”, and unceremoniously dumped by the wayside as another casualty of free-market eutrophication. I shall close, greedily, with a final haunting passage from “Beyond Machines”:

“Capitalists as well as proletarians become the property of machines, although in different ways. Freeing themselves should therefore mean a freeing from, and not by means of, machines, and the question “Who should own the machines?” therefore means “Is there anyone or anything beyond machines?” This really should have been understood immediately after the Industrial Revolution.”18

Footnotes

- Vilém Flusser, The Shape of Things, Reaktion Books,199, p.88 ↩︎

- Marc Andreesen, Why Software is Eating the World, a16z, 2011 ↩︎

- Vilém Flusser, Gestures, University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p.152 ↩︎

- Geoff Walker, A Review of Technologies for Sensing Contact Location on the Surface of a Display, Journal of the Society for Information Display, 2012, p.20 ↩︎

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, Penguin, 2004, p.505 ↩︎

- Vilém Flusser, The Shape of Things, Reaktion Books, p.92 ↩︎

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, Penguin, 2004, p.423 ↩︎

- Sequoia, Engagement Drives Stickiness, Sequoia Capital Publication, 2018 ↩︎

- Yehuda Wacks and Aviv M. Weinstein, Excessive Smartphone Use, Frontiers, 2021

↩︎ - Elisa Wegmann et al., Social-Networks-Use Disorder, Sci Rep, 2020 ↩︎

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, Penguin, 2004, p.423 ↩︎

- Christian Fuchs, Digital Labour and Karl Marx, Routledge, 2014. ↩︎

- Karl Marx (n.11), p.420 ↩︎

- Vilém Flusser, Gestures, University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p.16-17 ↩︎

- Karl Marx (n.11), p.442 ↩︎

- Donna Haraway, Manifestly Haraway, University of Minnesota Press, 2016. p.11. ↩︎

- Vilém Flusser, Gestures, University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p.16 ↩︎

- Vilém Flusser, (n.17), p.16 ↩︎