Issue 11: Sweat

The Tyranny of the To-do List

Take multivitamins. Check. Buy cilantro and a head of lettuce. Check. Submit pitch to Adjacent. Check. These are items from my recent to-do list. And while I have completed all the tasks on my list, the victorious feeling of being “on-top of things” is fleeting at best. With every task I complete, I cannot shake the haunting feeling that there will only be more to-do lists to create, more tasks to complete, and more things to forget. The to-do list is a bottomless index of our hopes and anxieties distilled into a set of banal tasks. From managing social lives to careers, many rely on to-do lists, including me, to hold our lives together. The to-do lists never cease to replenish itself and we are swept into a never ending game of cat-and-mouse with ourselves. It’s easy to feel like we are not doing enough, or we simply have not found the right method or technological tool to resolve our woes–finding the perfect way to manage our to-do lists is no exception.

Between sticky notes, whiteboard scribbles, and various reminder, note taking, and calendar apps, my to-do lists are like a Rube Goldberg machine with a primary output of basic life tasks. I often joke to my friends that, “If it’s not in the iCal, it’s not happening”. As much as I like to poke fun at myself, it is sometimes terrifying to admit that without to-do lists, my life would be chaotic and out-of-control. It is not out of the question that, without my intricate to-do list system, I would fail to show up to work, buy food for myself, or maintain important relationships in my life within the time that I have. I cannot pinpoint when I began to rely on to-do lists to conquer the Herculean task of maintaining work-life balance, but I cannot imagine my life functioning without them. There are simply more tasks I need to complete on a regular basis than I can humanly hold in my mind. As a diligent user of to-do lists, I have built a system that works (most of the time). And yet, this delicate life balance I have achieved over the years using to-do lists still fails to address the increasingly Sisyphean nature of modern living. Lately, I have begun to question whether it is my to-do lists that are becoming unmanageable or if it is contemporary life itself.

The phenomena of the neverending to-do list, or better yet, the pressure to conquer our to-do lists, is a symptom of our condition living under late capitalism.1 Jonathan Crary (2014) in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, theorizes that 24/7 markets and globalization has subjected humans to a “non-social model of machinic performance” that suspends life itself.2 In other words, the capitalist demands of never ending growth and the expectation of 24/7 access to our labour has conditioned us to exist as isolated machines. Under these socioeconomic conditions, it is no surprise that money is a top stresser in our lives.3 And yet, the meaning of life for people is quite the opposite–when survival is not at the forefront of our minds, most of us would much rather focus on our loved ones.4 With the limited time and resources we have, how can one balance the need for survival and meaning in life? Faced with the bleak reality of what it means to exist in the modern world, we have been seduced to turn to the to-do list. The myth of advancement in technology seems to be that every new tool carries a promise of a better world. To-do lists, in all its analog and digital forms, is no exception. Every app. Every gadget. Every extension. Every new technology we are presented with compels us to believe that our lives can be a bit easier under late capitalism. We convince ourselves that if only we completed our to-do lists, then we could have a bit more time to spend with our family and friends. Or if we better prioritized our time and managed our tasks with more efficiency, then we could be more successful and happy. We have grown desperate to optimize our condition in a failing world. Rather than criticizing the reality of our crumbling material conditions, many of us have turned towards to-do lists as a tool to restore focus, organization, and calm in our lives. But what exactly is the source of our deficiency in focus, organization, and calm? The answer could be our failure to master our to-do lists, but it could be something greater.

We are all looking for the answer of how to survive the capitalist grind of wage labour, while maintaining the ability to experience human joy and intimacy. It is a seemingly impossible task. This is because it is. The demands of capitalism and the human desire to lead a meaningful life are inherently incompatible. In fact, Australian feminist philosopher and psychoanalytic theorist Teresa Brennan, cited by Crary (2014), “coined the term ‘bioderegulation’ to describe the brutal discrepencies (sic) between the temporal operation of deregulated markets and the intrinsic physical limitations of the humans required to conform to these demands.”5 These demands for our labour, of course, are always gendered, racialized, and classed, where an undue burden is placed on those who face discrimination under an interlocking web of oppressive systems that interact with capitalism. A loss of sleep, social isolation, and increased stress, are all symptoms of this clash between market demands and human limitations. Humans are not built to operate as machines to fulfil the appetites of contemporary global markets and its greedy elite stakeholders. Capitalism’s demand for access to our labour, energy, and time continues to seep into our personal lives beyond the realm of work and it appears we have accepted our fate. In a cruel and paradoxical turn, our desperate endeavour to hone our ability to juggle work, school, and life using technology has baited us into consenting to our own subjugation. We have turned life into an entity to be managed rather than experienced. A simple internet search query for “to-do list” yields pages and pages of results for “best to-do list apps” that are updated each year without fail. According to the xenofeminist collective Laboria Cuboniks (2018), technology and its uses are “fused with culture in a positive feedback loop,” and we live in a culture that values capital, extraction, and expansion by any means necessary.6 Is it possible that we are asking ourselves the wrong questions? Maybe the question is not, “What is the best technology that can help manage the endless tasks in my life?” And instead we should be asking ourselves, “What needs to change so my life is no longer a series of endless tasks to be managed?”

The to-do lists are never-ending because it is a necessary distraction for stifling our ability to invest our energy in what is important. The more our energy is consumed by the pressure to fuel the impossible velocity of endless growth under late capitalism, the more we lack the ability to enact collective social change. The task at hand is not to find the best to-do list app or to hone our task management abilities, but to shift the collective conditions that require this of us. Crary (2014) argued that in a 24/7 world facilitated by technology, one experiences an atrophy of longstanding shared experience while never attaining the gratification or rewards promised by the latest technologies.7 In other words, the allure of joy and fulfillment promised by technology is never realized and we are left with a deteriorating experience of our shared humanity. There is no sustainable way for us to experience a human life and maintain the level of labour expected of us in the modern world. It is a trap and we are lonelier, more isolated and stressed as a result. Technology presented to us as inherently progressive and innovative solutions to our modern condition is merely a distraction. In defence of Luddites, sociologist and author Ruha Benjamin (2019) argues that skepticism and opposition of technology and automation is actually a protest of the “social costs of technological ‘progress’ that the working class [are] forced to accept.”8 It is hard to imagine a scenario where we can to-do-list our way out of the cruel machine of capitalism that is increasingly enabled by technology. If collective liberation from the unavailing grind of contemporary life is what we seek, then we must question our own participation in it.

At the heart of the to-do list and our desire to optimize it is the belief that life can be managed and the demands of capitalism can be overcome with enough organization and focus. This belief, as we have explored, is one that hurts us more than it serves us. I have certainly been guilty of the desire for total administrative mastery of my life, only to find that the peace of mind from a completed to-do list is quickly subsumed by the insatiable appetite of capitalism, and thus another to-do list is born. In The Xenofeminist Manifesto, Laboria Cuboniks (2018) declares that there will be “No more futureless repetition on the treadmill of capital, no more submission to the drudgery of labour, productive and reproductive alike, no more reification of the given masked as critique.”9 So, what would it take to end the tyranny of the to-do list and jump off the treadmill of capital, as it were? The answers to this question are perhaps not as far out of reach as we think.

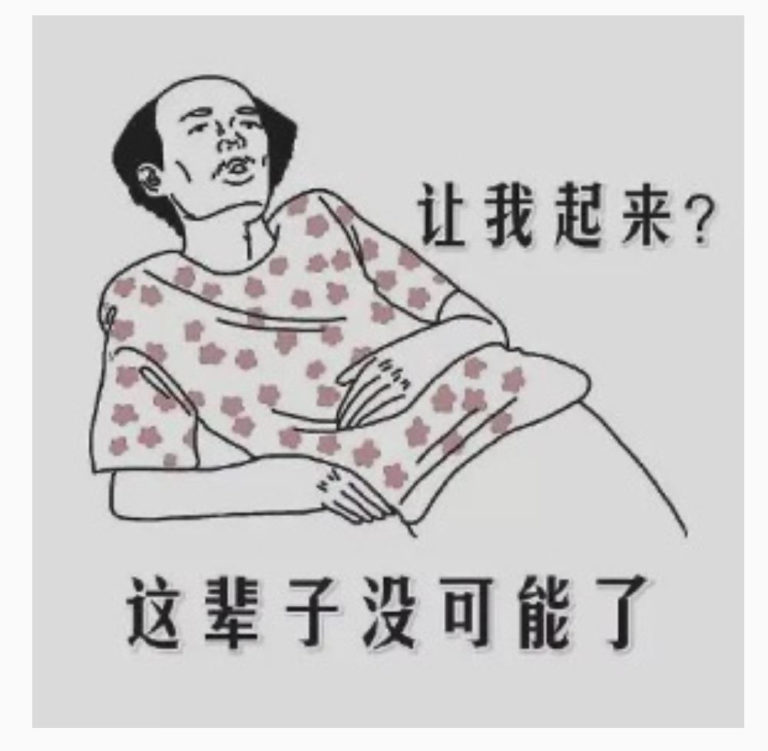

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been several contemporary social movements born out of an anti-capitalist spirit. Take, for example, the 躺平 “lying flat” movement catalyzed by young people in China. At the core of this movement are young workers who “reject the culture of overwork” and recognize that overachievement cannot overcome the rising costs of living in the 21st century.10 In a similar vein, we see the rise of “quiet quitting”11 and “The Great Resignation”12 in North America.13 The power of our collective refusal to meet the impossible demands of capitalism does not go unnoticed, though. In the case of the “lying flat” movement, social media groups were banned from discussing how one can participate for fear of its effects on the economy and the ability for China to be rejuvenated as a nation.14 A meme that was circulated widely on the internet in 2021, during the rise of the “lying flat” movement, depicts a person laying leisurely with a pondering look on their face. The accompanying text in Chinese reads “让我起来?这辈子没可能了” which translates to “You want me to get up? That’s not possible in this lifetime.” This image encapsulates a spirit of refusal with an acute awareness of the material conditions of contemporary life that deem this act of leisurely resistance necessary. It is precisely the recognition that individual merit cannot overcome the failing conditions of late capitalism that makes the “lying flat” attitude significant. Reflecting on the daily routines of human life prior to the advent of capitalism, much of one’s day was spent doing “nothing”. Of course, “nothing” is not actually nothing. “Doing nothing”, in this case, refers to our participation in anything deemed unproductive, and therefore, invaluable in the eyes of capitalism. Or in the words of artist, educator, and writer Jenny Oddell (2019), “[…] nothing is only nothing from the point of view of capitalist productivity.”15

Perhaps all our to-do lists, schedules, and lives, could use a little bit more “nothing”. Cheekily, I am reminded of a scene from the “The Pink Purloiner” episode of SpongeBob SquarePants where Patrick Star crosses off “nothing” on his to-do list.16 For me lately, “doing nothing” looks like making time to be horizontal in order to enjoy the present moment. In this act of embracing the nothingness of the moment, my true thoughts and feelings emerge in the clarity shaped by the absence of a pending to-do list. In this restful refusal of productivity, I feel more connected to myself and the world around me. Making time for daydreams, rest, and boredom, even, is more radical than we may think. Odell (2019) emphasizes that the “point of doing nothing” is not to refresh ourselves so we can be more productive workers, but rather it is “to question what we currently perceive as productive.”17 Furthering this sentiment, Crary (2014) reminds us that sleep is a “radical interruption” in the flow of sleepless 24/7 markets and it is in the state of pause that “the imaginings of a future without capitalism begin as dreams of sleep.”18 Perhaps, in the act of doing nothing, we too, can imagine a kinder and more human future. These movements and thinkers bestow an important message upon us: the endless investment in capital, facilitated by our labour, is merely a path to our own demise. And the search for technology to assist us in this toiling is a mere feedback loop of capitalism’s own making. In the spirit of liberatory refusal, may the next and only task on our to-do lists be “nothing” too.

Footnotes

- Drawing from the work of Ernest Mandel and Fredric Jameson, “late capitalism” can be defined as the epoch from post-WW1 to the present where industrialization and commodification has accelerated both its pace and reach across the world and into more and more aspects of human life, including culture. For more context on “late capitalism”, see Mandel’s Late Capitalism (1975) and Jameson’s Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991). ↩︎

- Crary 2014, p. 9. ↩︎

- In 2023, the American Psychological Association conducted a study on stress in America which revealed that for people between the ages of 18 to 64, money is the top stressor in their life. ↩︎

- A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2021 showed that “family” was the top answer for what people of all ages regarded as a source of meaning in life. I have used the language of “loved ones” because I believe the definition of family ought to include both chosen and given/biological family. However, “family” in this study most likely refers to biological family, since “friends” were regarded as a separate priority category. ↩︎

- Crary 2014, p. 15. ↩︎

- Laboria Cuboniks 2018, p. 17. ↩︎

- Crary 2014, p. 31. ↩︎

- Benjamin 2019, p. 37. ↩︎

- Laboria Cuboniks 2018, p. 13. ↩︎

- See https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/china/china-tang-ping-trend-work-culture-b1862444.html ↩︎

- “Quiet quitting” describes a worker striving to do the bare minimum at one’s job without being terminated. ↩︎

- “The Great Resignation” was a term coined in 2021 to primarily describe the economic trend of American workers resigning from their jobs en masse. ↩︎

- For more context on quiet quitting and The Great Resignation see https://www.businessinsider.com/quiet-quitting-great-resignation-trends-economy-outlook-leaving-jobs-davos-2023-1 ↩︎

- See note 10 above. ↩︎

- Odell 2019, p. 15. ↩︎

- Brookshier et al., 2006. ↩︎

- Odell 2019, p. 16. ↩︎

- Crary 2014, p. 128. ↩︎

Works Cited

American Psychological Association. (2023, November). Stress in America 2023 [Press release]. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2023/collective-trauma-recovery

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology. Polity.

Brookshier, L., King, T., Banks, S (Writer). (2006). The Pink Purloiner. (Season 4, Episode 79a) [TV series episode]. In S. Hillenburg (Executive producer), SpongeBob SquarePants. United Plankton Pictures.

Clancy, L & Gubbala, S. (2021, November 21). What makes life meaningful? Globally, answers sometimes vary by age. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/11/23/what-makes-life-meaningful-globally-answers-sometimes-vary-by-age/

Crary, J. (2014). 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Verso.

[Illustration of a person lying flat accompanied by Chinese text]. (2021). https://www.sohu.com/a/483442371_100140961

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Verso.

Laboria Cuboniks. (2018). The Xenofeminist Manifesto. Verso.

Madison, H. (2023, January 21). ‘Quiet quitting is the natural sequel to the Great Resignation’ as workers still rethink their jobs 3 years into the pandemic. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/quiet-quitting-great-resignation-trends-economy-outlook-leaving-jobs-davos-2023-1

Mandel, E. (1975). Late Capitalism. Verso.

Muzaffar, M. (2021, June 9). An entire generation of Chinese youth is rejecting the pressures of hustle culture by ‘lying flat’. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/china/china-tang-ping-trend-work-culture-b1862444.htmlOdell, J. (2019). How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House.