Issue 12: Becoming

Being Without Brains: Exploring Slime Mold, AI, and Non-Human Spatial Intelligence

The imminent destruction brought about by the climate catastrophe has brought something of an epistemological void along with it. The axioms that have taken us to this point are clearly flawed and unreliable…seeing as they have taken us to this point. Our intuitive reaction to the problem is to solve it – but our systems of knowledge are entrenched in the very practices and beliefs that are culpable. We find ourselves in a situation where we must think beyond ourselves – despite our ways of thinking being inextricably linked with the very practices that have brought about our current condition. Establishing a new way of relating to the world demands stepping outside of the current one – and that is most easily accomplished when there are others to look to, however briefly.

Though humanity’s ecological understanding will never precisely mirror an AI’s or a slime mold’s (nor should it, living in such a way would not only be unattainable but likely very uncomfortable) considering the breadth of possibility when it comes to different ways of thinking is pivotal to disrupting the assumption that the world (and our place in it) is as we know it.

Relying on physarum polycephalum (a species of slime mold) and Chat GPT (a brand of artificial intelligence presenting its own ecological harm) as case study examples of how non-human forms of intelligence approach spatial problems and understand their environments, I will explore the possibilities that might exist for reconceptualizing humanity’s physical place.

Slime mold and Chat GPT exist at opposite ends of a spectrum—one an organically occurring protist largely unaware of human life, the other a synthetic byproduct of human thought with no physical experience of the world. (barring conditions such as these…I’m about to put it in a maze). That said, neither entity has a brain, senses, or body according to the conventional anthropocentric understandings of those terms – and yet each are able to synthesize and retain information according to the anthropocentric understandings of those terms, applying it in various creative ways in order to solve tangible problems that exist in the world.

The Problem at Hand

The ongoing tension that has characterized the dynamic between human technology and nature (for so long that it has widely become considered natural itself) is rapidly approaching its climax. The anthropocentric ethos that nature and the cosmos themselves are tools to be wielded and mastered is running up against itself – discovering that its demands have grown so large and so destructive that its continued life demands the destruction of its own preconditions. The increased complexity and urgency of issues regarding how humans relate to their spaces is unlikely to respond solely to solutions founded on the very axioms that fostered them. The climate catastrophe is largely caused by a deeply embedded and culturally produced flaw in the way that humans relate to space – thus it is unlikely that continuing to engineer that same space into submission by way of the same repeated tactics will resolve much.

Two Intelligences, Two Approaches

Chat GPT exists as a software program with its “experience” being continually disseminated across the personal devices of various users. It does not occupy a single location and though the user interaction of typing a prompt and receiving a response may qualify as an interaction between Chat GPT and the physical world, it is not a direct or felt reaction to physical stimuli. At this point in time it is impossible to touch Chat GPT…and vice versa.

Similarly, slime mold does not have a conventional body or a centralized “self” with which to identify. Physarum polycephalum begins its life in a single-cell amoeba-like form before repeatedly reproducing via binary fission. When all of the local free-living slime mold cells have consumed all of the food in the area, they spiral together to form a new whole. This becomes the mature plasmodium which solves problems to navigate towards its food through an intuitive chemical attraction known as chemotaxis (Jabr, 2012). If you put a bit of slime mold plasmodium into a petri dish with another slime mold plasmodium, they will become one. There is not a firm boundary of self when it comes to slime molds.

The Experiments

Study 1: ChatGPT’s Approach

ChatGPT’s understanding of space is a purely abstract simulacrum of humanity’s own relationship with it. While it has no way of experiencing what it is to be in a maze navigating it, it is able to draw upon patterns in human conceptions of mazes in order to understand the prompt and draw logical conclusions about an effective approach. It is able to recognize the image of the maze and analyze its shape from a two-dimensional perspective, understanding its form in terms of lines and edges as they exist and are represented across a Cartesian plane.

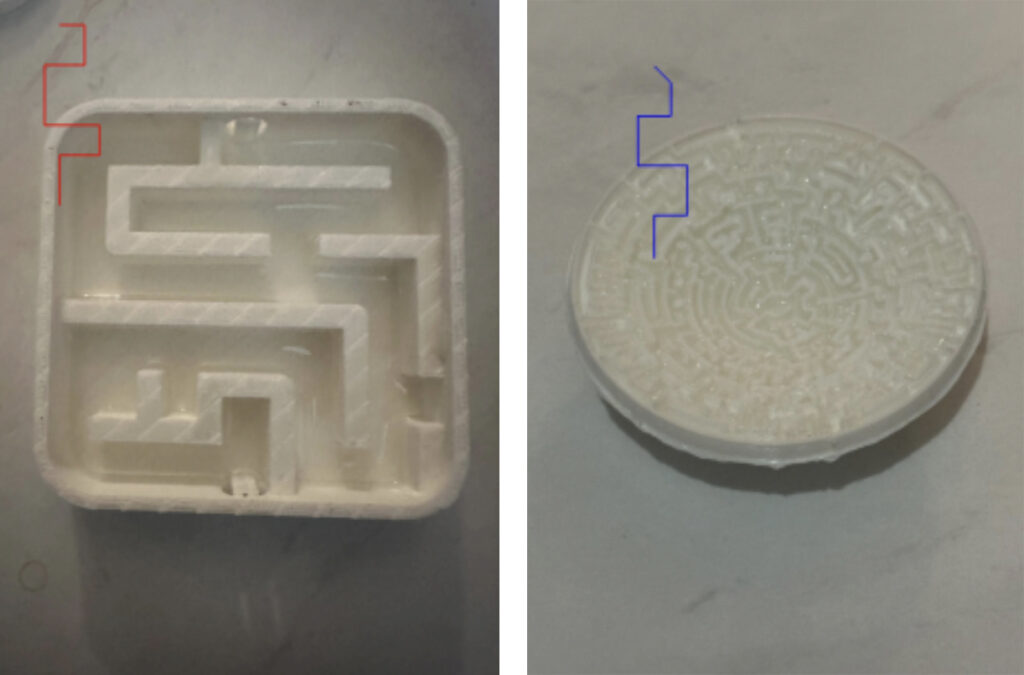

The first study asked ChatGPT 4o to solve two 3D-printed mazes. The program was fed photographs of the empty mazes and ChatGPT responded with high-level descriptions of how mazes in general can be solved before. It then provided a marked-up image with a visual solution to the maze (Fig. 2 and 3), as well as the code for how that new image was produced. Using Python, ChatGPT opened the provided image and estimated and connected a series of coordinates that it predicted to be the correct route.

When asked how it gathered those coordinates, the program explained that since it “couldn’t interact with the maze directly or calculate the path programmatically due to the limitations of the tools used” it instead “estimated the points based on the image layout and typical maze-solving logic” and “approximated the coordinates visually.” It determined the likely starting point for this maze based on the usual template for mazes of this style. It then observed where there appeared to be corners and intersections, and used that to progress logically toward the predicted endpoint.

Study 2: Slime Mold’s Approach

For more detailed footage of slime mold growth and to get a better understanding of how slime molds grow, visit the online archive that was created alongside this experiment.

Swabs of physarum polycephalum were taken from the plasmodium and added to each of the 3D-printed mazes. The mazes were lined with a layer of nutrient-free agar pour and oats were added to the endpoints of each maze. In the case of the larger and simpler maze, the slime mold found the path straightforward enough that it did not need to explore a wide variety of routes. In the case of the labyrinth, the mold found itself largely unbounded by the maze structure. The mold progressed along a direct and linear path toward its food source, climbing over the “walls” of the maze. That said, this slime mold progressed more slowly than the one in the larger and simpler maze as its approach was that of trial and error. Though its intuition in these cases proved too accurate to send it in the wrong direction for very long, its process was nonetheless propelled by active and ongoing experimentation rather than any strategic plan declared at the start.

After the slime molds completed their mazes, the experiment was repeated with the introduction of additional food sources. I predicted that by complicating the situation for the slime molds, interesting things might be revealed about how it “prioritizes” and determines where to move first. However, this decision coincided with the Thanksgiving holiday and that meant temporarily transporting the operation to Colorado where my family lives. The slime molds were wrapped up nice and snug in cellophane wrap and taken to Laguardia Airport.

Despite the utmost precaution, tragedy struck. Much like the PLA mazes posed little challenge to the slime molds, their protective wraps did little to maintain a sterile environment. Life finds a way (Spielberg, 1993) – and it is not always the life that you want….or the life that you have become deeply emotionally attached to and in many ways psychologically dependent on. After only a few days in their new climate, the slime molds appeared to have been overtaken by the emergence of additional molds within their mazes. Though this had occurred to a lesser extent earlier during the experiment, these other organisms had so far always grown in superficial locations that could easily be cut out and removed. In this case, however, too many new molds developed all at once and quickly became embedded deep within the agar. There was nowhere to move them and limited time. The slime molds were declared deceased.

A Personal Crisis

Grief took hold and the future of the project became uncertain. Though enough evidence had been collected to conclude the project, the numerous ideological and ethical paradoxes behind it now seemed more abhorrent than ever.

Feeling that I had not only used but abused and killed my collaborators (and, in doing so, left myself forever deprived of the simple joy of waking up each morning to see how the slime molds had grown) I felt consumed by anger at myself and resentful of my newfound self-imposed loneliness. I was at a loss and did not wish to continue. Unfortunately, it was far too late to pivot. Doing so would have likely required a whole conversation or something. I decided to suck it up.

Saddened and disturbed by this state of things, my parents intervened. They generously rescued the slime molds after the distraught author returned to New York and lovingly nurtured them back to health. They purchased petri dishes and sent photos with updates about their continued growth. I was looking forward to reconvening with them and eventually taking them back to New York. It was a holiday miracle.

The Paradox of This Approach

This experiment is far from a perfect exercise. Slime mold and ChatGPT serve as accessible examples of alternative ways of thinking, revealing the vast variety of possible world understandings—yet their use for this purpose remains paradoxical. The most apparent contradiction lies in using ChatGPT to explore new modes of thought despite its entire knowledge base being derived from the internet, a space shaped exclusively by human thinking. Rather than transcending human cognition, ChatGPT merely reformats it, reflecting and often amplifying cultural biases while occasionally hallucinating new ones. Though it processes vast amounts of data at an unmatched speed, presenting a different mode of interpretation, it remains inherently tied to human-created frameworks.

There is further irony in using ChatGPT to reconsider humanity’s unsustainable relationship with nature, given its substantial energy consumption and the AI boom its release accelerated. Rather than serving as a neutral tool, its environmental impact complicates its role in discussions about sustainability, arguably undermining the experiment’s aims.

Similarly, working with slime mold purchased from Walmart and cultivated in a petri dish underscores another contradiction. While the experiment seeks to challenge human dominance over nature, it ultimately reinforces it by treating the slime mold’s life as a means to a human-centered end. The mold does not navigate a maze out of necessity but under artificially imposed conditions designed to satisfy human curiosity.

These paradoxes are not easily resolved. The experiment relies on the very systems and assumptions that have contributed to the problems it seeks to address. In many ways, it exemplifies how proposed solutions to modern crises often mirror the very structures that caused them. It is nearly impossible to think beyond a given framework when every aspect of one’s knowledge and experience is shaped by it. Yet this realization only deepens the societal relevance of this experiment.

Lessons from Two Nonhuman Minds

These experiments revealed fundamental differences between how an entity with a purely conceptual understanding of space approaches problems and how an entity with a purely experiential knowledge of space approaches problems. While unsurprising and to a fair extent intuitive, these results provide a more thorough, detailed, and tangible perspective on how issues of space can be approached.

Chat GPT’s approach was informed purely by its knowledge of rules – the rules of a maze’s structure, of Cartesian space, of Python code, and what it is able to analyze and draw within an image. The slime mold, being altogether unaware of any existing rules, ended up operating in a more creative way and succeeded in achieving its goal. A poignant limitation of artificial intelligence stems from its status as a product of human rules. Its strength lies in its remarkable ability to respond to, analyze, and output in accordance with these rules – but its existence and understanding of the world ultimately consists exclusively of them. ChatGPT has no conception of a maze beyond the idea of “maze” that humans have provided, and that conception is a constraint.

Artificial intelligence carries extraordinary power in that it can comprehend and apply rules at a never-before-seen speed and scale, but it cannot ever move outside of or think beyond the world of (specifically human) rules. In order to envision truly creative solutions to the problems of the modern world, it is essential that individuals, organizations, and public entities push themselves to think in terms more similar to that of the slime mold – relating to their challenges in a dynamic and open-ended way without obstructing their own path with self-imposed constraints.

Systems as Tools, Not Gods

At the risk of sounding melodramatic, we are the gods of the systems that we create. Yet that responsibility and authority is understandably daunting, and it is often far easier to adopt the view that our systems are our gods. In accepting this, we save ourselves the trouble of continually “reinventing the wheel” and enable ourselves the freedom of conscience that comes with deferring to a higher authority. The crux of the slime mold vs. artificial intelligence juxtaposition can be summarized as the contrast between an entity that extrapolates solutions from a knowledge of existing structures and one that invents its solutions as it encounters and experiences a structure.

As human beings we do both. The structures and rules that we invent save us, for example, from needing to prove on a case-by-case basis that the floor will support our weight when we get out of bed in the morning, or that pairing two objects with two other objects there will be four objects, or that random violence is wrong, or that fertilizing crops will help them grow. If we did not invent rules and systems and each individually questioned every assumption down to its axiomatic core each time it was applied, we would live in a considerably more difficult (albeit possibly interesting) world. At the same time, people are fallible and the world is continually changing. Though fertilizing crops has worked and does work, it is not impossible to rule out the possibility that this could someday cease to be the case. We can and we need to create generalizable statements based on our past and current experiences in order to communicate and cooperate, but that means that all of our knowledge and decisions are only as good as the fractional and often incorrect slices of information that we have about our past and present. What has been true and seems to be true is all that we have to go on, but still offers little to no assurances about what we can expect to be true.

As a result, we must take our cues from the slime mold and resist becoming too attached to our own patterns. Though we need our systems and rules, we must remember that they are ultimately tools that we rely on to navigate the world – not ends in and of themselves – and they are not guaranteed to always work or to work forever. We must resist the urge to regard our existing structures and precedents as things that are in any way elevated beyond, less fallible than, or otherwise greater than our own present judgments.

With all of this in mind, we are not literally gods. There are structures that we cannot simply circumvent by sheer force of open-minded will. Slime molds can decide to climb outside of the boundaries of the maze, but they cannot decide to simply evaporate and teleport to their destination on the other side of the maze. Slime molds work a certain way, mazes have certain properties, and matter (as we observe it) adheres to certain laws. Though at some quantum level the states of and boundaries between all things may be a bit more changeable – at this point in time, for the sake of practically navigating reality, it serves us to accept some rules.

As such, trying to think like a slime mold is not a suggestion that we abandon all faith in our epistemological systems. Rather, it is a suggestion that we resist the temptation to rely on precedent as the cornerstone of our decision-making patterns. It is a reminder that we should see our tools (structures, systems, rules, and ideologies) as tools, and attach only to our understanding of these tools as things that aid us rather than things that we must adhere to at any cost. It is a reminder to keep our systems in perspective and to remember that the goal is to get from point A to point B, not to follow the maze as it was meant to be followed.

Facing the increasing complexity of the world demands an increased capacity for complexity, and artificial intelligence seems designed to suit this. Yet there is substantial risk in rendering our own systems indecipherable to ourselves. Rules that exist for long enough tend to enforce themselves, and habit has always been a particularly strong form of executive branch. AI may be the keystone in humanity’s tomb as we set about burying ourselves in bureaucracy. It is now more important than ever that humanity turn its gaze outward and keep its own systems and self-imposed structures locked squarely in perspective alongside the broader context of the world and the cosmos. Understanding the mazes that we invent from a top-down perspective so that we can move through them as strategically as possible has its place, but we cannot allow ourselves to do so while forgetting that it is ultimately just a plastic barrier, and you can still climb over or crawl around.

References

“23.2b: Protist Life Cycles and Habitats.” Biology LibreTexts, Libretexts, 23 Nov. 2024, bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_(Bou ndless)/23%3A_Protists/23.02%3A_Characteristics_of_Protists/23.2B%3A_Protist_Life_ Cycles_and_Habitats.

“AI Policy, Now and in the Future (Annotated).” One Hundred Year Study on Artificial Intelligence (AI100), ai100.stanford.edu/2016-report/overview/ai-policy-now-and-future/with-2021-annotations. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024.

Bitton, Mathis, et al. “How U.S. Cities Are Using AI to Solve Common Problems.” Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business Review, 3 Dec. 2024,

hbr.org/2024/12/how-u-s-cities-are-using-ai-to-solve-common-problems.

Jabr, Ferris. “How Brainless Slime Molds Redefine Intelligence.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 13 Nov. 2012, www.nature.com/articles/nature.2012.11811.

“School of Life Sciences.” Slime Mould Facts, warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/lifesci/outreach/slimemold/facts/. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024.