Issue 4: Bodies and Borders

Who Shot Gil Naamati? Or, A History of Video Games

Gil: There is a game aspect to protests. I saw it as a sort of game, too…

Interviewer A: Until you got shot.

Gil Naamati is a game designer living and working in Tel Aviv, Israel. This text refers to events surrounding a protest in the West Bank in 2003, one month after Gil completed his mandatory service in the Israeli military. The text is based on transcriptions of conversations held in 2010. This is the first time it is published. (In the image: the soldier who shot Gil preparing to fire. Mas-ha, West Bank, 12.26.03)

Interrogation

GIL: We accept this idea of the military being an absolute necessity, that’s totally beyond debate. And if you refuse to enlist and become a soldier1, you are refusing to take on the most fundamental burden of all. Unlike other types of contribution to society, [serving mandatory time in the Israeli military] is considered an unquestionable necessity. If you don’t accept this burden, you’re seen as a freeloader.

INTERVIEWER A: That’s true, serving one’s time in the Israeli Defense Forces2 is always presented as a precondition for participation in our society. But the concept of burden seems secondary to me—because the burden is not spread equally among soldiers, of course. What I consider central is that to be considered part of Israeli society, you must agree to be a tool at the mercy of the military system. You must agree to the idea that your personal well-being will play no role in how you spend these years. The only well-being that matters is that of the system you’re serving. This is a thing that doesn’t happen in education, or other systems where the state is seen as something meant to serve you, the citizen. The whole point of basic training is to make you understand that you’re nothing but a tool in the hands of the system. That you need to do what you are ordered, even if you fail to understand why. Basic training accustoms you to a state of being terrorized. And the low-ranking soldiers tend to be more unruly than the officers. The guys you hung out with, Gil, they always maintained a high degree of irony, really pushing the idea of ‘have your cake and eat it, too’—you were doing whatever it was you were ordered to, while always maintaining a deep hatred of the IDF, a real loathing of that system.

Gil being visited in hospital by Moshe Yaalon, the IDF’s then-Chief of Staff

GIL: Right. You either align your goals with those of the military, become a commander, get to be in charge of things, become part of the system—which means you also get to make your own decisions and have some say in shaping your surroundings, and even get to express yourself—or, you remain a low-ranking soldier and try to stay as indifferent as possible. Present, while not truly there. This path leads to weird situations, but it also gives you freedom, because you don’t need to make any decisions of your own. You sort of make yourself small. And by the end of your service you become sort of… you just keep your head down and move slow.

INTERVIEWER B: That’s what you were like as a soldier toward the end of your service?

GIL: Yeah, even though honestly it did get fun toward the end. We had a PlayStation. Some of the guys would just sit inside all day, drink big bottles of coke, and play games.

A History of Video Games (1)

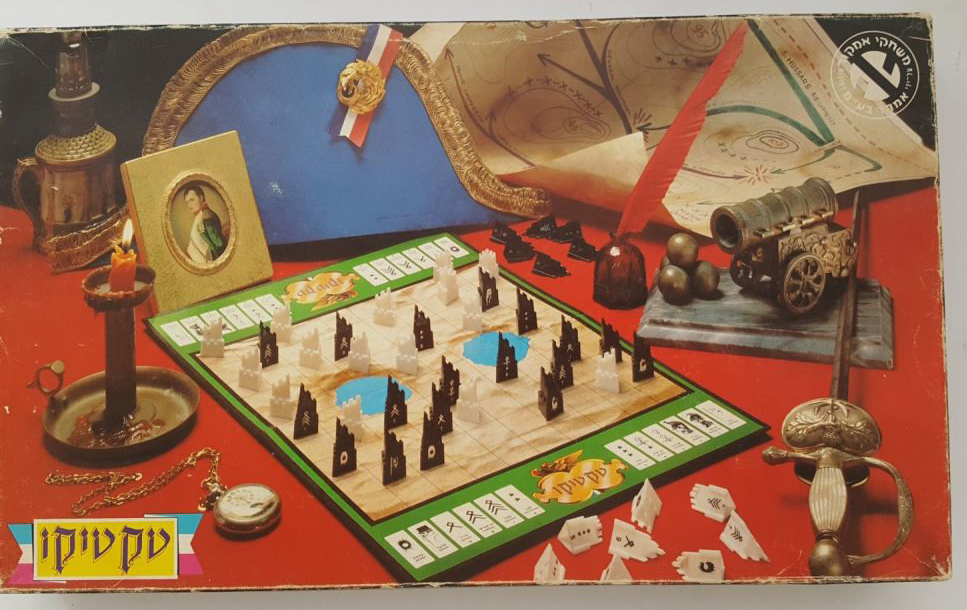

GIL: At first, my friend Idan and I wanted to create a strategy game for two people playing on one computer. Something like chess or Tactico, but with real action. Archon was a game like that. It was a big influence on us. Archon is really one of the most interesting games ever made. It’s a cross between a board game and a shootout. It’s from the early 80’s—the golden age of retro games, before they were retro. It’s sort of like chess, but instead of the pieces taking one another, they have duels—each player fights through his pieces, and the winning piece kills the loser.

Another video game genre—Real-Time Strategy—was born from the game Dune II. The main novelty in RTS was, well, the real-time. Until then, fighting games were played in turns and through symbols—like chess. You would pick which piece to move, tell it where to go, and watch the results. RTS games did away with that symbolism. You no longer needed to move some marker or object that represented a combat unit—now, you chose and moved the unit itself. You didn’t really move it, you gave it an order—but you’d see what was going on in the battlefield the whole time, and you’d see your soldiers get killed.

These RTS games added the element of action to strategy games. The genre was born soon after the mouse was introduced. Video games are of course always deeply influenced by the player’s means of control. The mouse allowed for the simultaneous control of many different combat units, and also for the player to be absent from the game interface: the player was suddenly represented by the cursor, which is invulnerable—it’s like a metaphor, not really there.

Interrogation

GIL: My parents were kind of torn. On the one hand, they were angry about me going to the protest (against the erection by Israel of the West Bank wall. For more on this, see notes. Throughout this article, regular brackets denote editorial clarifications, while square brackets are used for paraphrasing of spoken text). At one point my father said: “If you’d have gotten killed, it would have been the worst, because your death would have been over that, over total nonsense.” They didn’t understand why I was involved with those ‘crazy Anarchists (Anarchists Against the Wall, an anti-occupation direct action group)’3. But at the same time, my dad was really angry. Really, really angry. At a certain moment, the idea that the military was lying really sunk in for him. He went to speak at some conference, he was really angry and he got it—he really took my side. Before this episode, his faith in the system was total—and then when this happened, it broke.

B: In what way was the military lying, and what was this faith that your father had in it?

My father was certain that the military would conduct an investigation and acknowledge their mistake, punish those responsible, and admit that a wrong had been done. But they didn’t admit anything.

A: And what was the lie?

That we protesters threw stones [at the IDF soldiers], that we were armed, that we had our faces covered, that we were about to attack the soldiers. A whole string of lies.

B: Who lied? The media? The courts?

This was what the military said in their statement. There was lots of news coverage when it happened. And I was just out—I couldn’t deal with it at all. Only once, after I was wounded, I went to speak on TV with (news anchor) Rafi Reshef4.

A: How did that go?

Pretty good. I think I chose my words well. But I just said the standard stuff: “We went there to show our solidarity with the Palestinians.” That’s the only sentence I remember saying. I said the things I thought I was supposed to say. And I was in this state of high. This was right after I woke up, 24 hours after I woke up. It was crazy, everything was a mess and I didn’t understand a thing. There were lots of people everywhere.

And my mother, too—on one hand she felt that the right thing to do was say how supportive and proud they were of me that I went and expressed my opinions. But on the other hand, what I did really upset them, I think. They were constantly supportive, but on the inside they were… It was a mix. I come from a normative sort of place, so how did I all of a sudden become—somebody that comes from a sort of mainstream place, who is ok with that, and suddenly he’s way out on the sidelines, radicalized.

B: Did your parents know you were going to a protest (in the West Bank against the construction of the wall)?5

No. I didn’t tell them. They got a call from a friend of mine, Yotam. They were in Jerusalem, at a relative’s show opening. And they got a call, “Gil was shot.” It was a horrible experience for them. And I hadn’t been honest with them—I hadn’t told them I was going—and that’s one of the things I’m most embarrassed of.

A History of Video Games (2)

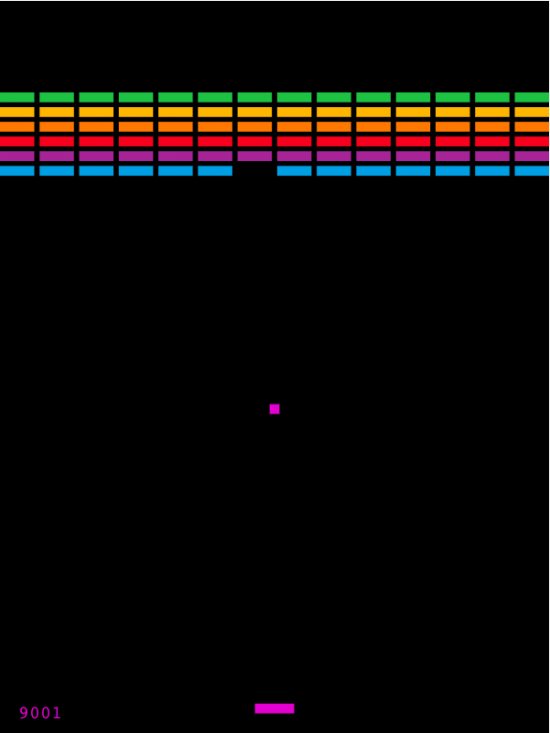

Pong was, if I’m not mistaken, the very first commercial computer game. It’s a two-player game. And after Pong came Breakout, which was an attempt to make a single-player Pong game. And Pong also led to Space Invaders. These games are all considered legendary, and were of course massive successes that had a huge impact on the way video games look today.

Interrogation

A: Do you have any footage you filmed there?

No. My camera was hit by a bullet. I used to have the pants [I wore to the protest], with the holes—all drenched in blood. The only thing I still have from back then is my organ donor card, full of blood. Yeah, I have it somewhere. Anyway, so there was a dirt ramp not far from the fence6, and all the Palestinian protesters were standing on it. And then all at once—all of a sudden—the entire group of (Israeli anti-occupation) protesters started to run forward toward the fence.

B: And at this point did you see soldiers?

The soldiers were on the other side of the fence, and I remember the protesters charging forward, but I can’t remember if the soldiers started firing warning shots in the air7 before this charge or after it. It happened all at once, everyone running forward. And that’s when things really got started. The protesters started shaking the fence and the soldiers shot in the air and it was a big mess.

B: The soldiers were firing into the air while the protesters were shaking the fence, and during this time you were still in the back?

Right, I was in the back.

A: Oh, so you didn’t run forward?

Of course I didn’t run forward! I’d decided ahead of time I would not get actively involved.

B: And the protesters heard the shots but continued anyway?

Right.

A: They didn’t think they would be shot at directly.

Right. The protesters were expecting non-lethal riot control measures, nothing beyond that. Everyone assumed the worst that could happen would be to get hit by a rubber bullet.

Protesters escaping tear gas at a demonstration in the West Bank village Bil’in, 2005

B: The protesters thought the soldiers firing in the air were shooting rubber bullets?

I don’t know what they thought. I don’t know what I thought. Nobody mentioned the possibility of real bullets. It was never even considered. The vibe was just ‘come with something to cover your face, because they are going to fire tear gas at you.’ That was it. And that was when I ran forward and started filming. And it felt like I was in some kind of movie. And it was very exciting to be part of it. It’s a feeling of adrenaline, of doing something real. [Anarchists Against the Wall] had a philosophy of direct action. Doing something, not just protesting.

A: So everyone had run forward, and then at some point you joined them?

Right, I was filming. I ran forward, then back, filming, watching. But there was this one protester girl who was having a hard time cutting through the fence.

A: Do you remember what she looked like?

She wore cool clothes. Curly black hair, pulled up. Crazy hair with all sorts of pins in it.

A: She looked ‘like a radical activist.’

Yeah. Everyone there looked very radical. It was all pretty scary. (A and B laugh). I was truly scared of these people, really.

B: So you saw this girl and —

And she wasn’t managing to cut the fence, she was having a hard time.

B: How was it being cut?

With wire cutters, I think.

B: Can those cut through such a fence? It’s a big fence…

If you cut strand by strand. Those wires were really thick.

B: But it wasn’t a barbed wire fence, right?

No, it was a gate.

B: Oh, the protesters were trying to cut the gate?

Right. And I remember thinking it was a bit stupid—it’s a gate, so all one needs to do is cut the chains locking it, and it would be open.

B: Last year at a demonstration in [the Palestinian village] Biddu8 I saw [Palestinian] protesters bring down a gate of the fence. And then the Border Police9 came, and detained one or two and forced them, as a sort of educational act, to put the gate back in place. It was pretty impressive how the protesters hoisted up that gate and put it back in its place—how everything went back to the way it was in a second. It was depressing.

A: You said you were scared of the other protesters. Did you speak with any of them on the way to the protest, on the way to the bus?

No, I kept to my group of friends. That’s how I am, I don’t really mix in.

A: So you came over to help the girl, and then what?

And then I just started cutting like crazy.

A History of Video Games (3)

When I played Starcraft against my roommate in Jerusalem I usually lost. Because Starcraft is a management game at heart, and I’m a shitty manager. Anyway, what’s interesting is that in this game your most crucial resource is your attention. You can only see a small part of the battlefield at any given moment, and you can only do stuff in areas that are visible. In other areas, your units act autonomously: they will obey your orders blindly. You tell them to go to a certain point? They will go there even if they are under fire. You tell them to go attack an enemy? They will attack and chase it, suicidally, even if it’s not worth the effort or the enemy is a lot stronger than they are. When you are near a unit, you can give it specific orders based on the situation—but when you aren’t around your units are just AI, artificial intelligence, with no decision-making capacities. They just blindly carry out the last order given to them.

Interrogation

B: You fell to the floor?

At that point I didn’t fall, I was just looking at my foot and I could see the hole. I saw a hole in my foot that was white and red. In my foot. In my pants. And then I lost consciousness. There’s a blackout I can’t remember. And when I came to I was on the floor with my leg like that and people holding me.

B: ‘Like that’?

My leg was in a position that made no sense.

A: You were shot in both legs?

Yeah, first they shot this one. (points to right leg)

B: Oh! They shot more than—you took a few bullets?

Yeah.

B: Oh wow, I didn’t know that.

A: Two bullets?

Yeah. But one didn’t do much harm, it just left a scar.

A: So the first bullet, the one you felt, didn’t do—

Didn’t do much.

A: That one (points at left leg) did the real damage?

Yeah, that one did the real damage. And I don’t remember that one. I don’t remember it hitting me. don’t remember it at all.

A: Where did it hit?

Here, right above the knee.

A: And the damage was because it hit the knee itself?

No, it hit right above the knee. Luckily it didn’t destroy my knee. It broke the bone and hit a central artery. And that’s it, I only remember being carried away. And Yotam said something really stupid, related to something he had said earlier in the day, “Let’s keep things funny.” And I said, “Yeah, funny till you get shot.”

A and B: While you were being carried off?

(Laughing) Yeah, that’s what I said.

A: While you were being evacuated you said ‘funny till you get shot’ in response to something he’d said earlier?

Yeah, earlier. When we first got to the protest, he said, “Let’s keep things funny.”

B: And when you were being carried he said that again?

Yeah, he said something like that.

B: As encouragement?

I don’t know why he said it.

B: Was he carrying you?

Yeah, he was among the people who were holding me, I remember that.

B: And then you lost consciousness?

And then I just remember being taken to some little old beat-up car, to the back seat, and—the way to the back seat, that’s it. Besides that, I can only remember the darkness before waking up.

B: Where did they evacuate you?

I was taken to some place, some (local Palestinian) clinic that had no medical equipment, no nothing. I was given a lot of intravenous therapy, I must have lost a lot of blood. And then somehow Levinski managed to get an ambulance to take me to some checkpoint10. In the video I watched later, I saw that the—the protesters were yelling at the soldiers that I’d been hurt, telling them to call an ambulance, but the soldiers didn’t call one. And so they cursed at them.

A: Who cursed at who?

The [Israeli] protesters were cursing at the soldiers. And the soldiers were saying something like ‘Go ask help from your beloved Arabs,’ something like that. I don’t know. But I can’t speak about this part, because I was no longer…

Mas-ha

A History of Video Games (4)

Space Invaders led to some very successful imitations, and one of them—probably my favorite—is Galaga. In this image, you can see how similar it is to Space Invaders, and how, for example, it introduced the idea of enemy choreography: your enemies don’t simply materialize—they enter your screen while doing a little dance.

Interrogation

Everything comes crumbling down. Things suddenly seem stupid. The idea of having any sort of role loses relevance. This collapse becomes who you are. It annihilates all your other identities. Suddenly you’re just that. You’re just ‘the wounded guy.’ You’re just your foot. There’s a poem by Auden that says people wounded in war become just a hand, just a head. He says, Truth in their sense is how much they can bear11. You stop asking questions. You become concerned with how to just hold on. You suddenly realize how much you’ve given up and sacrificed just to see things from the other side. And all that become stupid. What becomes important is only your life, your health.

B: Do you suppose soldiers wounded in an actual battle feel the same way? Maybe they do get some solace? Your dad said it was lucky you didn’t get killed over ‘that nonsense.’ Whereas if you’d been wounded in, say, the 2006 Lebanon War, while supposedly ‘fighting for the homeland,’ it would provide those who get hurt—and their families—with something to hold onto. A feeling that this wasn’t all for no reason.

If I’d been wounded as a soldier in battle, I think I’d be much less confused. One does not need to justify the choice to enlist in the military—that choice is the only choice that’s legitimate. That’s what most people think, anyway, so it’s easier to live with. But going to that particular protest (Anti-wall attitudes are considered extremist and widely illegitimate in Jewish Israeli society)— there’s no power, no source of authority telling you it’s the right thing to do. The surgeon who saved my life told me “I don’t agree with what you did, but I saved your life anyway.”

B: It sounds like justification here is a real struggle for you. [As an anti-wall protester] you’re in the minority, in your ability to justify your actions. So the struggle is never won. You need to keep coming up with justifications to your family, to yourself, to your surgeon. What I’m hearing is that the need for justification is less urgent when it comes to things deemed normative, ‘pre-justified.’

Even though once it comes down to actually losing someone, or severe injury, that’s when it all comes crumbling down. Everything looks equally stupid.

A History of Video Games (5)

I’ve got a few strong childhood memories that relate to games like Xenon. I’d go over to a friend’s house just to play this game. I was hypnotized by it. There’s something exciting in the juxtaposition of the underwater alien world, the high-tech spaceship, the bizarre ‘boss’ enemies—you’d be fighting this huge lizard—and also the fact that you could buy extra weapons between rounds.

There were a few elements here that really came to define the genre: You’d always be playing a sort of spaceship; shooting at a few different directions at once; the background scrolls down, making it look like you are moving up; your enemies approach you in a sort of dance; and sometimes when you blow up an enemy you can pick up a prize.

Interrogation

B: Gil, our paths crossed twice. The first time was in [IDF military base] Shivta, when we were both in Artillery Division basic training. And the second time relates to the protest in which you were shot. During that time, I was an officer at the battalion, near Qalqilya12. There was a huge length of separation barrier there—which was brand new back then—and it ended in the village of Mas-ha (where the protest took place)13. And I don’t know exactly when, but the battalion in which I was an officer—the instruction officer—arrived there not too long before that protest. I was basically sort of the battalion’s operations officer aide, in the war room. That’s where all the surveillance systems were, and all the lookouts14 watching over the separation barrier. This barrier is a complex system that demands coordination by a lot of different forces—and this was the period when we were figuring out how to operate it. It was new to the military and also to our battalion. And this is when that Friday protest happened. There were lots of protests during that period, but most of them were in Qalqilya, not in Mas-ha or by the barrier itself. This was the period when the wave of protests against the barrier got started. And the protest [where you got shot] was one of the first of its type. And there was an infantry brigade that got there a few days earlier, they were stationed right by Mas-ha, and they were the ones who fired at the protesters. These soldiers weren’t from my battalion, but they were a company related to it, and we were in charge of them. And there were all sorts of logistical failures—they didn’t have non-lethal crowd dispersal weapons. And two or three weeks before that protest, my battalion commander kicked out the battalion’s intel officer and told me that from that point on, I was the acting intelligence officer. This role involved obtaining info about upcoming protests. We’d get alerts from the police. And that week, I actually knew there was going to be this protest at Mas-ha, but I didn’t think too much about it, because there was a lot of other stuff going on. We were much more concerned about a certain protest planned for Qalqilya that same day. That’s why nobody in the battalion was prepared for your protest.

Did you know about everything going on back then, in Mas-ha? Did you hear about the group of [anti-occupation] activists residing there with [local Palestinians]?

B: No, I didn’t hear about that. But there were other protests—I don’t remember exactly, but I think yours wasn’t the first protest.

[The protest I went to] was the second protest in which the fence was cut.

B: In that case [the military] definitely knew about it.

A: Where did the first protest happen?

I don’t remember, I just remember watching a video of it. It was a really powerful video, where you can really see people cutting through the fence, next to some ditch. Cutting it, really cutting through it, while the soldiers were standing right next to them, doing nothing—because the activists doing the cutting were Israelis.

A: I assume you saw this video after the protest where you were shot?

No, before it.

A: You saw it before?!

(Laughing) Yeah, now that I think about it.

A: Do you remember what you thought when you were watching it?

I remember that—it was obvious to me that those soldiers couldn’t do a thing. I was thinking, great. I saw it as a sort of demonstration of power. Like, we have the power to do something against the bad guys.

B: I’m interested in the way you were thinking at the time.

I think I was full of anger. I was really angry at the military. [Being in it] was a total nightmare. I mean, it was ok, but towards the end I really hated that system so much. All the stuff you take for granted, life within that stupid system.

B: You were discharged two months before the protest?

One month.

B: One month?!

Yeah. I saw the video while I was still a soldier, and I thought, I’m not going to start anything while I’m a soldier—but once I’m out, I don’t have to cooperate, I can be more…

B: So you saw the video while you were in the military, and you felt like going, or you identified with what you saw, but you said, “I need to wait till I get discharged before I can do that.”

Right.

B: And this was the first [anti-occupation] protest you ever went to.

Yes, the first I ever went to.

A History of Video Games (6)

One interesting thing about video games is that the side you are on—and what you need to do to win—is predetermined for you. That’s why video games are always political, because who’s good and who’s bad is decided for you. The way that problem is dealt with has always been that the bad guys are unquestionably bad—aliens, zombies, monsters, Nazis. There’s also the sadistic genre, where the point is to kill innocents—like Postal—but besides that, it’s basically aliens, zombies, Nazis.

And terrorists, they were added to the mix only recently—in the 1st person shooters that at first were set in WW2, and eventually were set in the contemporary era—the Call of Duty series. When I was wounded I was actually right in the middle of the first game in the series, it was set in Normandy.

The fourth game in the series is set in the near future—there’s this part there where you play a secret agent embedded in a terrorist group, and you’re tasked with carrying out a bombing at an airport. Basically your mission there is to shoot innocent civilians. Whenever innocents were killed in games before then, it was always dark humor. But this game was different—it was serious and realistic and the fact that you were killing civilians was suddenly acceptable.

Interrogation

That’s how I felt, I think.

A: That’s how you felt?

Yes. ‘I got myself shot.’

A: You weren’t angry?

No.

A: Not at any stage?

Maybe at some point, but I don’t remember being angry.

A: Do you know who shot you?

Some guy called Nadav. I don’t know his surname.

(Pause)

B: I’m interested in what you’re saying about not being angry, and about blaming yourself.

I was angry that I got myself into a situation where I got shot. So many things that were important to me just disappeared.

B: You saw it as your own mistake, and you didn’t tell yourself “It’s the f— military, those soldiers who did this to me, who hurt me.” You are taking responsibility, essentially. You had no anger towards the soldiers who shot you?

I don’t think so. Maybe at some point I was deeply angry. But all the strong emotions just… dimmed. And I think I’m trying to—I sort of pushed them aside. The strongest feeling I had was fury at reality itself. It wasn’t directed at any particular soldier.

A: Fury about the very fact that this happened?

Yeah. I was never angry at that particular soldier. Also now I’m not.

A: When did you feel this fury? Right after it happened?

A few days later.

B: You were unconscious, at first, right? For how long?

Two days. I’ve got two empty days. During the first I was totally unconscious, and in the second I was apparently speaking, sort of semi-consciousness, but I’ve got no memory from that day.

—Break—

I heard there was a big mess at my kibbutz15, after I was wounded. I don’t know what happened. I disconnected. People were arguing over [what happened to me], blaming me. It caused a rift. I remember being told people were ‘talking’.

A: And what happened when you returned to your kibbutz?

Life went on, slowly. There was one day, after I came back from the hospital. A guy suddenly came in, this young guy from the kibbutz, totally drunk. He just walked into my flat—he’d meant to go into the neighbor’s flat, but he came into mine, my door was unlocked. He started talking and talking. About how everyone was looking at the scars, about how they knew. Some guy I sort of knew, but I’d never spoken to him before.

B: What scars?

My scars.

B: They are visible?

Yeah, when I wear shorts.

B: That’s what he told you? That people were looking at your scars?

Yeah. And then he spoke about ‘the Arabs.’ About how they would never forgive ‘us Jews.’ Something deep inside of him came gushing out. He was saying it was something everyone knew but nobody ever spoke about. “They will never forgive us, they will never forgive us.”

A: Who won’t?

‘The Arabs.’

A History of Video Games (7)

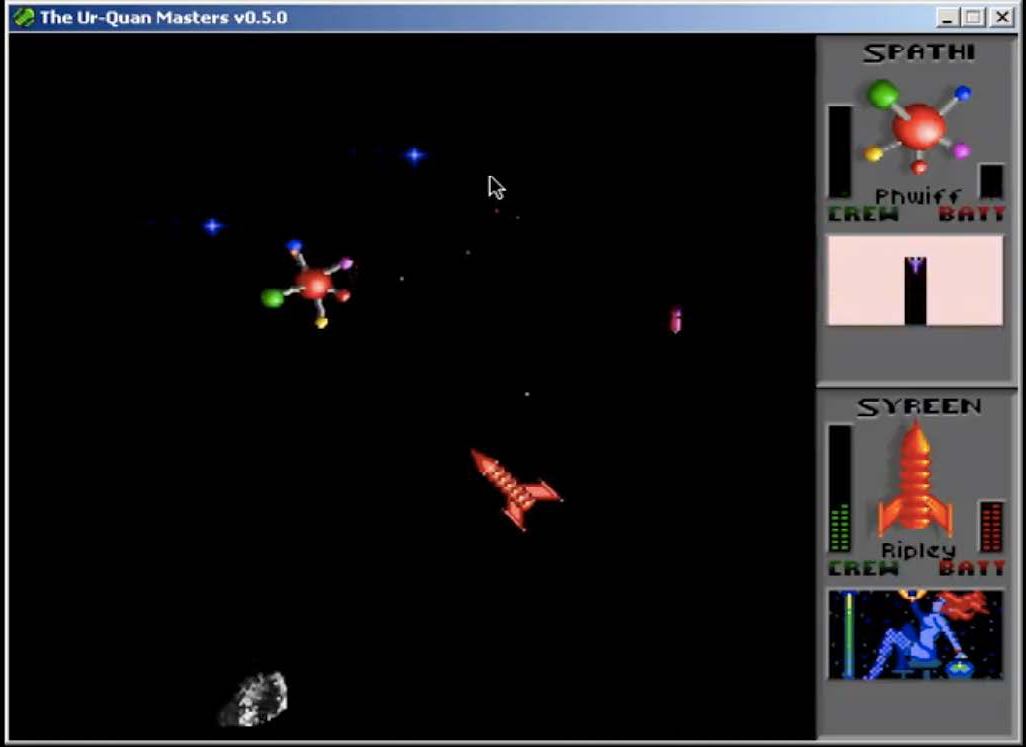

Star Control is another game that’s important in the context of two-player games.

It was a spin-off of Space Wars, one of the very first video games16. Star Control didn’t really do anything new, but it was revolutionary in its humanity and creativity. Suddenly, you had the option of which spaceship you wanted to fly, and each spaceship had its own pilot, a creature you could see through the little windows. These creatures had different personalities, and the spaceships behaved accordingly. Later in the game they develop stories and the possibility to play against the computer and really investigate the histories of the different alien races. It was one of the first games that succeeded in hooking millions of people thanks to a really good, funny and deep dramatic story. Which like any real sci-fi epic includes a war of armageddon, and some horrible genocide.

And I still remember the sentence the bad guys in this game say—these big dark octopus things floating above a huge mass grave full of the bones of intelligent aliens from across the galaxy:

We are the Ur-Quan Kohr-Ah.

The followers of the Path of Now and Forever!

You will soon die. Make whatever rituals are necessary for your species.

Interrogation

A: How did you feel when you saw the video [of your shooting]?

I don’t know. I was thinking, why are the protesters cursing at the soldiers instead of asking them to call an ambulance. That said, I wasn’t there, I was blacked out. I don’t know what was going on. But when I saw the video of me wounded, I was thinking, wasn’t there some different way to… I prefer to approach things in a reconciliatory way.

A: It sounds very difficult, watching a video of these [soldiers] who instead of saving your life, are going ‘let him die.’ It’s incomprehensible to me. But you’re saying that you didn’t see it that way—that your anger was directed at the protesters, not at the soldiers.

I had no expectation of the soldiers to help me. That seems like a totally unreasonable expectation.

B: It’s a bizarre situation, in which the guys who shot you are supposed to be the guys helping you.

On the protesters’ side, everyone was screaming, nobody stopped to say ‘Hold on, everyone stop, there’s a casualty here, can we have an ambulance sent?” Instead, they were shouting, “There’s a casualty here you mother—s! Get an ambulance! You’re letting him die! You are allowing someone to die!” And then, also, they went ahead and cut through the fence and finished the job.

A: You’re saying you’re angry that they kept playing the role of protesters while you were dying? ‘I’m about to die and you’re using it to scream at the soldiers.’ You’re saying someone should have just said, ‘pause this game.’

There is a game aspect to protests. I saw it as a sort of game too…

A: Until you got shot. You said that at the beginning of the protest, before you were wounded, while you were running you were feeling how ‘real’ the whole thing was. So on the one hand, at that point, while the direct action was taking place, you felt that there was something ‘real’ going on, something important. But then when you describe your feelings of watching the video of the protest, you say that when you got shot, that’s when it really got real—what had until then looked like a game. It’s interesting, this idea of what was real before you were shot, and what was real afterwards.

But regardless of whether or not it’s a game, you still expect—despite going to this event which really is dangerous—you still expect that your life will go on afterwards. You know what I mean?

B: And how do you feel today about what happened? Eight years later?

It’s part of who I am. It’s imprinted in me. It’s something I take for granted.

B: Do you feel like it changed your life, that your life would be totally different if this hadn’t happened?

Definitely.

A: Can you imagine your life’s alternative route, which this event derailed you from? Would you have still studied at Bezalel [Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem]?

Who knows. I’d probably study something creative either way. But I’ll explain what I mean by changing my life. I always had an urgent need to fit in, I always felt a bit abnormal. And right after I was discharged [from the military], I started working at a ‘normal’ place, with a ‘normal’ eight-hour workday. I’d wake up in the morning and go to work and come home in the evening and I was having a blast.

B: You’re talking about the one month before the protest, right?

Right, the month after my service ended—for the first time in my life, I felt sane… I was a chubby kid, and all sorts of nonsense like that, and I never really got through my adolescence. And that month was the first time I held myself together. I remember being discharged and feeling really good. Saying to myself, that’s it—all those problems are over.

A: And you still think it was foolish, going to that protest?

Today I look at it like—like it was something that had to happen.

B: So how did it change your life?

The moment it happened, when I got wounded, I was cast a huge distance off the main, central path I’d finally climbed onto. And since then, my routines never stabilized again—things like going to work, like everyone else. Suddenly I was back to living a bit differently.

A: You’d want things to stabilize? You’d want things to return to how they were back then?

B: Wait, I’m trying to understand what you mean by saying ‘then.’ This was just one single month after being discharged—

Yeah, it was a very short moment in time, a moment that symbolized ‘Gil becomes a regular person.’ That’s what that one month symbolizes for me till today.

B: I suppose this is the story you tell today, about that thing. When did you start thinking about your story like that? The way you tell it, Gil, you just recounted a story framework that’s basically a tragedy. In the sense that right before the protest there was this apex moment—which was then suddenly taken away from you.

A: And on top of that, from within the confidence of that one amazing month, you were driven to go to that protest. The passivity of your military service, which you described earlier on, was over—now you could go and do something, raise your voice loudly, and arrive at that moment, that ‘real’ moment.

It was something I was really scared of, going to that protest. It really made me uncomfortable. Part of the reason I did it was to overcome my fears. I usually opt for not doing rather than doing—and this time I’d decided to overcome my fear.

A: And how are those fears nowadays?

I’m less fearful today.

A: Even though your fears did come true?

(laughs) Yeah… That fear did stay with me for many years. The fear of realizing that your body is vulnerable. Living with such a realization is very difficult. A realization that came from being wounded. A realization that you could die at any moment, and everyone you love could die at any moment. It’s so bad, you don’t understand how people can even leave their homes. You live inside this sort of huge fear. It’s occurred to me that this fear is due to death being too close to reality, which is something one simply can’t live with.

A: One has to play pretend.

Yeah, one has to play pretend, and forget about it. I was scared of guns—for a little period after I was wounded I couldn’t play shooter games. And then I forgot. I came to understand that I just have to forget. (Laughs)

B: Forget what?

The realization that I could get hurt. That I’m vulnerable.

A History of Video Games (8)

Star Control 2 had a really interesting narrative. And a beautiful thing about it was how the strength of each different spaceship was informed by its particular story. For example, there was a race of hippie birds who believe in being nice to everyone, keeping good karma. They’ll still attack you if you mistreat them, and their spaceships are shaped like butterflies! And when you blow them up, sometimes they just get reborn. It was the first time, to my knowledge, that the idea of karma made an appearance in video games.

Interrogation

B: When did the thought ‘this event changed my life’ first occur?

At first, I thought it messed up my path toward stability, the path of leaving the madness behind. I thought [my shooting] was what stopped me from continuing on the normative route. But I think those thoughts were a bit exaggerated. I sort of mythologized that one month before my shooting. I remember it as a month of being in a sort of constant state of bliss. In retrospect, I realize it wasn’t like that. And it’s possible that what I’m telling you now isn’t totally accurate, too.

B: What’s for sure is that this became the way you tell the story. It’s a bit like interviewer A said—one can understand your attending the protest as part of your process of letting go. A period that’s different, followed by the injury, and then life changes course. Any event, as such, is always an act of analysis. In order to be an event, it demands to be recognized by others. And it requires certain acts—to be told as a story, for example. The idea of testimony is a good example. When you describe ‘what happened,’ you endow it with significance—as an event. This is interesting in the context of protests, military arrests, military operations. These things are always constructed as stories: They start with some sort of briefing, an explanation of what’s going to happen: there’s a plan, a rationale, a beginning, and an expectation of what’s supposed to happen. That’s how these things get constructed as events.

A: During the protest, you felt like this ‘movie’ was all about you. That you, Gil, were its hero.

B: Right, like what you said about filming as you were running, and feeling like you are part of something.

A: You wanted to be on the unsafe side of the movie screen—on the side that gets looked at, not on the side of the observer.

Right. There’s a wish to really live, to feel alive. You want to be close to things. You want to really see them. To know what it’s like to really be there.

A History of Video Games(9)

Doom, from the late 90s. Not only did it invent the first person shooter—the most popular and messed-up genre of all—it also introduced to the gaming world the concept of a death match: a multiplayer game played through the web. Everyone plays together in the same world, and sees things from the perspective of a character with a gun. The point is to kill all the other players. But when you kill another player, they don’t really die—they get reborn a few seconds later, and you gain a point. It takes a few seconds for the body to disappear. That’s because bodies are a computing load on the graphics engine, so there’s a need for them to disappear—but it’s also very important that you, as a player, get to see the corpse of the other player you just killed. So the corpses don’t disappear right away—they stay there for a few seconds, and then float upwards and disappear. Or at least that’s what it was like in one of the games that evolved from Doom, a game called Unreal. A new word was invented for this type of death: Fragging. ‘I’ve been fragged.’ Frag means death in video games.

Oh, and what’s especially great is that sometimes you can still see your own body before it disappears, when you are reborn after being killed. And in World of Warcraft, if you’re dead you appear as a ghost in a graveyard, and in order to be reborn you have to run back to your body and get into it.

Interrogation

A: What’s crazy to me, Gil, is how forgiving you are. On the one hand, you want to tell us about how the very meaning of reality crumbles apart the moment you’re wounded like that. You want to do a sort of tikkun17, you want to tell people something they may not know. But at the same time, you express understanding of people who say you made a bad mistake, people who dismiss the meaning of your action, and you yourself say you made a mistake. But you were shot!! And you hadn’t done any harm to anyone! It’s insane! You were shot!

If you’d have asked me back then, my answers would have been different. But now that it’s in the past, and we’re ok…

A: But how are ‘we ok’?

If you’d have asked me four years ago, while I was still taking meds, methadone, constantly falling asleep in classes, not managing to keep things together—

B: You took methadone for years afterwards?

I had pain in my leg, where I was hit. I took methadone until about four years ago.

B: You kept taking it for four years after you were wounded? Your leg still hurt?

Yeah. And back then, I was angrier. Now you’re talking to me at a point when the anger is more abstract. I’m not living it.

A: But here you are, still trying to figure it all out.

Yeah, it’s important for me to deal with it. And now I can do that now due to the fact that my anger is abstract. You’re asking if I’m angry, but anger is an emotion. Until just a few years ago, it was very hard for me to face all this. When I’d watch the video of my shooting I’d watch it like this—(puts fist in mouth). I remember watching it and hoping that somehow, somehow—this time it wouldn’t happen. You know?

A: And beyond anger, did you lose faith in anything you used to have faith in? You spoke about your dad, who lost his faith in the system. Maybe, as opposed to him, you weren’t surprised that the military lied about what happened?

I was surprised. And what surprised me even more, is that I didn’t lose even more faith than I did. That even an event such as this merely kickstarted what would be a long process. It took many years until my opinions became more radical than they were then.

B: Do you think that at the time, telling yourself ‘I made a mistake’ made things easier for you? Maybe it’s harder to say ‘Everything is arbitrary,’ or ‘The government and the soldiers can’t be trusted’?

Yeah. In my head, things were divided between the ‘crazies’ and the extremists on one hand, and some notion of ‘most people’ who are pretty sane on the other. And that I’m part of the ‘most people.’ This idea that it is actually the majority that poses the threat to me is something that only developed over the past few years. Before then, I didn’t consider the majority to be the extremists. I didn’t join Anarchists Against the Wall as some kind of rebellious thing.

A: And even with that group, you didn’t feel like you were ‘with extremists’—you didn’t befriend the people there who you perceived as radicals—who sort of scared you.

Right. Once upon a time, if I’d see someone with, say, a lot of tattoos, I’d get a bit stressed out. Today, the ‘unconventional’ scares me a lot less. Today it’s actually the normative-looking people—the crew cut types—who make me think ‘Uh-oh, these guys are probably [off-duty] soldiers.’ Today it’s those people who stress me out. Just like the military does. These people who… it just stresses me out.

A History of Video Games (10)

There’s this one game which does a very interesting thing to your head. Usually, you see the world from either the point of view of the person who’s shooting—as in a 1st person shooter—or from above, controlling one character and firing at others—in a 3rd person shooter. But in this game, you saw the world through your enemy’s point of view. You controlled the character with the gun, but you had to shoot the characters through whose eyes you’d be seeing. A 2nd person shooter, basically.

Interrogation

I do think about that soldier. If he had known what he was about to cause… He was just sitting there, aiming, and that’s it. And maybe I’ll never walk again. On the way to the car, when I blacked out, I might have not woken up, and that’s how my life would have ended. In that ‘frame’ with the Palestinian car. A crappy little car. I still remember the upholstery. It could have ended right there. That’s what death looks like. That’s what the end of your life looks like. And why? For no reason at all. And by the way, that soldier could have just shot [a warning shot] in the air. He did think it out. He didn’t shoot out of fear. He was very calm. He lay down on the ground, by that car, found a comfortable position, took his time aiming. Later, I heard that one of the journalists who was there—there were a few Israeli journalists over by the soldiers—said that the soldier asked for permission to shoot over his comm. There was a commander there—named Shay, from a nearby town—and he gave the permission. And I can just imagine this soldier going, ‘Ok, you know what? I’m just going to shoot someone in the leg. I’m only 19 years old, I don’t even know what I’m thinking. I’m hungry, I need to piss, and I want this whole protest thing to be over with. So hey—let’s just shoot someone in the leg. Let’s see, who should we shoot in the leg? That guy over there—he’s the tallest.’

A protest in Tel Aviv in response to the shooting of Gil Naamati. 12.27.03. Photo by Oren Ziv, courtesy of Activestills

A History of Video Games (11)

In video games, the body is something that’s not constant. You can change it and switch it freely. But despite that, it’s got to bleed and fall to the floor and stop working. And then another one is born.

Interrogation

A: So really, Gil, you’ve told us two stories. The first is about disillusionment with the establishment, a story of transformation. Nowadays, you identify with types you once feared. In this story, your shooting revealed an important truth. But there’s another story here, too: the story of Gil’s struggle to become a normative person. In this story, you were almost victorious, having completed your military service. You went to the military when the military symbolized a precondition for becoming a normal person. You succeeded, you completed your time there, and came out in one piece. Not just physically. You didn’t lose yourself, you didn’t become a fanatic, you didn’t become an officer, you did what needed to be done without giving up who you were. People respected you—and I say this as someone who served in the same unit as you—they respected you for who you were. For how you read poetry in the tent, the way you treated people. A lot of people try to change and adapt their character to the military—but you didn’t try to change. You won a sort of big victory in the military. And then, that month after you were discharged—according to this story—was a month of victory celebrations. Here you are, coming back from the military, a winner, and you are going to become a normal human being. But then the ‘dark side’ of Gil suddenly surfaced and pushed you, through this bliss of victory, to that protest, and ‘saw to it’ that you would suffer a total and absolute defeat, that the idea of ‘normality’ would be lost forever.

So you’ve got these two stories. One describes a difficult truth that was exposed in this event. It’s a truth that’s ingrained in you, now. It’s a truth about the state, and about the military. It’s a hard truth, but it’s better to see it than to be blind to it. There’s a link in this story between your victory celebrations and this discovery, which came to you maybe ironically, but not totally tragically. As for the second story, which I think you accept, to a certain extent, this story is about the quest for normalcy, and it also relates to what you were recounting about the kibbutz and about the social difficulties there, and your parents’ feelings. The question is, which of these is a story that you can take with you? Because there’s a sense in which they are not compatible. One is a story of a tragedy, in which you were doomed to fail despite your efforts. The second is a story of the dialectics of discovery, and in it you keep this tension, within the military system, till it reaches a breaking point in the moment of the shooting. But the process keeps going on afterwards, when you go and make your peace with what the shooting did to you. These are two different stories.

Well, that’s interesting. And it’s true—you want the safety of normativity, but at the same time you don’t want to live inside some fantasy.

A History of Video Games (12)

In Galaga, about a minute after the game starts, there’s this moment when your spaceship is captured. This enemy ship comes over, sends out pulses, and captures your ship: And then your ship joins the Space Invaders dance. Now that I think about it, the whole dancing thing actually comes from aerial displays.

And then if you destroy the enemy ship that captured it, your ship becomes yours again, and connects itself to you, and you shoot with double firepower.

This element of losing and regaining your spaceship disappeared from the genre, but what did stick around is the element of extra ships joining themselves to you and shooting in tandem.

Last week I was playing Galaga and an annoying thing happened. I let this bat creature take my spaceship, and then I shot it, but I fired too much! My first shot killed the bat, and the second shot destroyed my ship, which was right behind it. I shot myself.

In these games it was important to gain as many points as possible because there was no way to save, so every time you ran out of lives you’d need to start all the way at the beginning. The only way to get more lives was with good scores. And of course, back then the high-scores were important—you would put your name into a console listing all the players’ achievements. So in order to get the most points from the bonus level, you needed to intentionally lose a ship and then get it back.

Interrogation

B: Gil, do you still want to be friends with ‘the guys with the crewcuts?’ They suck! I make such an effort to not look like one of them. I don’t want anyone to even think that I used to be an officer in the military.

It comes and goes. I don’t want to be so ‘different.’ I would have wanted a normal life. Yeah, I still do have such a wish.

A: What’s ‘normal’?

A job, that’s normal. To complete the military, then go study something for four years, work eight hours a day, and just accept that. I don’t know… No, what I’m saying isn’t totally true. It’s hard to define what safety is. Maybe it means knowing that what you’re doing is ok. A huge part of my life I had this feeling that I was always making all the wrong choices. Again and again, I was doing the opposite of what I should have been doing. And being shot was one more of these things—one more stupid thing that I caused to myself. I told my dad: “I just did something stupid.” But you know what? I’ll probably do more stupid things in my life…. I can’t rely on myself, I do stupid stuff. What does normal mean? Knowing that the choice you made was the right one.

It’s Not About You

For Paul, of the New Testament, the moment of godly revelation was falling off his donkey. Revelation for me was really, well—God destroys everything, too. The crumbling down of everything was my revelation, in a way. There was a course I enjoyed at [Bezalel Art School], a seminar on the idea of holiness. There’s a discourse that doesn’t consider god as a protector god—but rather, as a terrible god. I remember being very moved reading what Pinchas Sadeh18 wrote about god attacking Moses. God’s whole monstrous side is something that really speaks to me, this animalism…

B: Which is the prophet who looks at god and sees a monster? Ezekiel, maybe? You look at god and suddenly realize god’s a monster…

There was Daniel, who saw a monster made of different parts. It had a head made of steel.

A: And there’s the story of Job, who was complaining about what God did to him despite his being a good and decent man. And Job’s friends, describing the power of god, tell him it’s impossible that god would punish him for no reason: “You probably did something to deserve it!” And eventually God speaks and describes his power and says that most of the rainfall he brings down lands in deserted places, in the sea and in other places where it makes no difference to anyone. Rain is not a prize, and drought is not punishment—both are coincidental in relation to humans. Maybe what God is telling Job is: “It’s not about you.” In no way is God punishing Job, because the question of what Job does or doesn’t deserve is in no way part of God’s calculations—which do define the life of Job.

B: But in the case of Job that’s not true—God was lying, it later turns out he made a bet with the devil.

A: Right, when you take the time to tell someone that you don’t care about them at all, it only shows that you do care… But God was telling Job that there was no good reason for his suffering—that he just got a raw deal…

Job as a radical lefty activist… With God telling the devil: Look at that guy Job, doing everything that he’s supposed to, serving in the military, the works… (The three laugh)

A: And Job, he wasn’t even up to anything—he was just some well-behaved guy.

—