Issue 4: Bodies and Borders

You are (check one): ☐ Stateless / ☐ A liar

Our categories of identity are increasingly hard-coded in menus and checklists. Must we accept a world of this or that, with no space for in-between or none of the above?

We usually think of national borders as demarcations made in physical space. Indeed, in a fundamental sense, these boundaries are manifested as restrictions on the movement of people and goods, usually imposed and policed by governments.

But such borders, of course, also exist in our minds, where they are constantly subjected to forces that are not physical in nature. When does the color red become orange? When does a bush become a tree? What makes two groups of people the same, or different? The very act of making sense of our surroundings is one of defining borders. Our minds perceive and interpret the borders between categories.

As a designer and technologist who holds dual Taiwan-US citizenship, I find myself constantly facing the ways in which border struggles play out in databases and computer programs. China’s challenge to Taiwan’s very sovereignty is defined and enforced not only by government actors, but also by executives, technologists, and designers at corporations, who design programs that determine if one can pass a checkpoint, get a job or access services. Digital borders, like physical ones, are areas of political contention. For those of us who shape them, the border between geopolitics and user experience is often blurry. And just like conflicts over physical borders, digital borders have implications on the economy and on our identities.

No In-Between

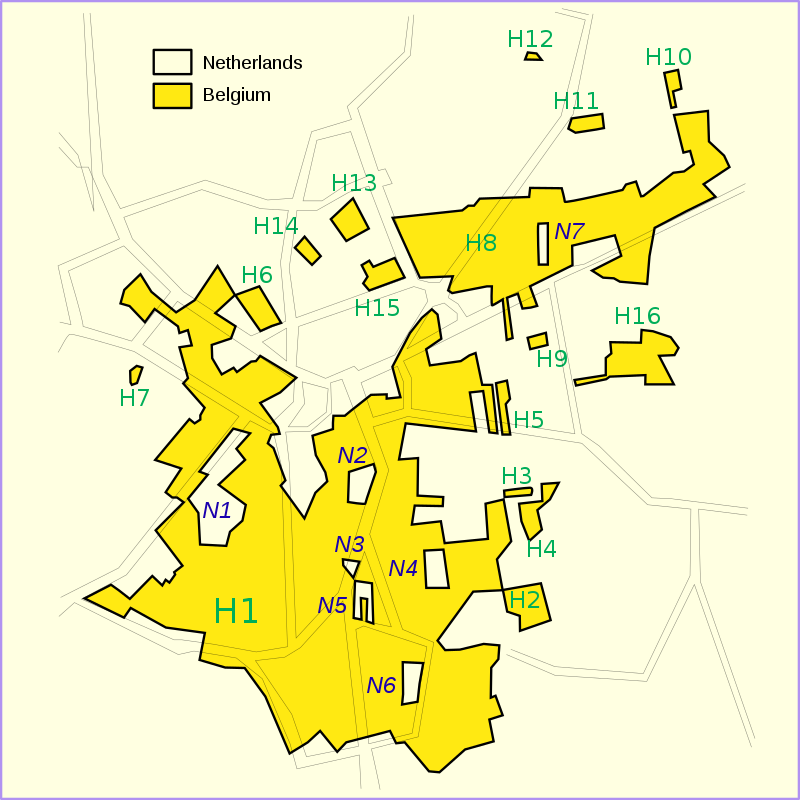

In geopolitics, physical borders can be complicated and porous. Straddling the border between Belgium and the Netherlands, for example, one finds the twin towns of Baarle-Nassau and Baarle-Hertog, both made up of intricate enclaves and exclaves of Belgian territory in the Netherlands and vice-versa, some of which are no larger than a single building1.

In digital domains, the categories of nationality and identity often become hard-coded in drop-down menus and checklists. You are either this or that. The binary allows for no in-between or none of the above.

I fell in the in-between. A human resources form, part of a hiring database program, forced me, in effect, to lie about my own identity when a few years ago I was hired as a consultant at the United Nations. As part of the onboarding process, I had to choose my place of birth from a drop-down menu. I am a dual US and Taiwanese citizen born in Taiwan, but due to geopolitics, Taiwan was not an option in the drop-down. Choosing “United States, “China,” or “Stateless” would have been a blatant untruth, but I had no choice.

In my case, this did not lead to trouble. But similar situations have had consequences for other Taiwanese citizens. Taiwanese journalists, visiting students, and tour groups have been denied access to UN buildings. And, much worse, different countries have deported Taiwanese citizens accused or convicted of crimes to China instead of Taiwan.

Taking Sides

The Chinese government has recently pressured international airlines to label Taiwanese cities as “China” on their websites. The Trump administration made a statement calling China’s actions “Orwellian nonsense.” But for the most part, US airlines have complied with China’s demands, seeking to continue operating in China.

As a designer and technologist, my work is subject to the rules and regulations of the territories in which I operate. I think of public policy as essentially a design constraint. The same goes for businesses, which must follow the laws of the jurisdictions in which they operate. But how do we design and operate international businesses with constraints that are contested like in the case of Taiwan’s sovereignty and de facto independence? There is no neutral position when we are forced to take sides. In the case of Chinese government pressure on US and international airlines, it is not just a matter of the international airlines complying with Chinese law in China. Rather, Chinese government demands have global implications beyond the borders of the People’s Republic.

This political pressure has implications on the user experience. User-centeredness is a core principle of good design: Ideally, design choices should reflect what is good for the user. In practice, of course, we must balance choices with business objectives and the policy constraints of where we operate.

Regardless of your position on the Taiwan issue, it is clear that China’s political agenda forces companies to make design choices that run counter to user-centered design principles. Taiwan has its own immigration rules and currency that are not under the control of the People’s Republic of China. Thus, an airline or travel site that lists Taiwan as “Taiwan, China” is potentially misleading for users unaware of the de facto situation. Such wording could easily, for example, led them to get the wrong visa, or change the wrong currency while preparing for their trip.

Controlling  the Digital Language

the Digital Language

Application of brute force to software design recently lead to a rather absurd result, when Chinese pressure caused Apple to censor the Taiwanese flag emoji for iOS users whose location was set to “China.” Rather symbolically, this resulted in a bug that enabled anyone to crash a vulnerable device by merely sending a text message with the Taiwanese flag. This is another case of geopolitics getting in the way of good software design.

While not usually regarded as an especially consequential form of communication, the emoji character-set provides rich examples on the machinations of hard digital borders, and the impact of software design on our identity and worldview.

Not unlike issues of emoji representation of skin-color or gender identity, those wishing to express affinity to a contested nationality may find themselves face to face with the fact that an inherently political design choice has been hardcoded into their operating system. Is your flag an emoji or not? There are flag emoji for both North and South Korea, as well as for Israel and Palestine. But there are no flag emoji for Catalonia and Tibet.

For many of us who communicate online, emoji are an extension of our language. Riffing on Wittgenstein’s famous quote, “the limits of my language are the limits of my world,”2 one could say that the limits of our emoji are also the limits of our world. I could wave a Tibetan or Catalan flag at a physical protest, but unlike a Scottish independence protester, I cannot make an equivalent political point using emoji.

It is critical to ask who has the power to define the borders of language and the extensions of language like emoji. Some languages like French have official academies that set rules of official usage and coin new terms for innovations and borrowed foreign concepts. But while the French Academy created the term courriel for email, many French people continue to use the English term. The Academy can define, but they cannot enforce. Speakers of French have the power to make their own choices about their language usage. But as users of emoji, we don’t have that choice. The decision about which countries or territories get emoji flags has been made for us. We do not currently have the power as users to extend the character set of emoji. Linguistic borders are fluid. Digital borders are hard.

Border Offence

Traditionally, defending a physical border is essentially a matter of maintaining a defensive position. Hold the line. Protect territorial integrity and sovereignty. These people may pass. Those people may not. Within one set of borders, there is a certain set of rules that apply to business and design. In another set of borders, there is another set of rules.

China’s so-called Great Firewall is also a form of digital border defense. The Great Firewall is a term that refers to a set of policies and technological infrastructure that limits or blocks the ability of internet users in China from accessing foreign websites or applications including the BBC, Facebook, and Twitter. The Chinese government also practices outright censorship and cracks down on political dissidents and citizens who speak their minds. Recently, China has censored images and references to Winnie the Pooh in response to a trend where Chinese internet users made memes comparing the cartoon bear to Chinese premier Xi Jinping. In another case, a man was arrested for asking in an online forum why Taiwan cannot be its own country.

Banning websites within China and cracking down on freedom of expression are examples of authoritarian censorship within China’s borders. But we are also seeing a new kind of censorship that goes beyond physical borders. In the case of China’s pressuring of foreign airlines to remove references to Taiwan, we see a kind of border offense, a projection of Chinese power and worldview beyond China’s borders. The airlines that have removed references to Taiwan on their sites have not just done so on their sites aimed at the Chinese market, but for their sites targeted to non-Chinese markets as well. The Chinese state is not cracking down directly, as it does within China, but instead it has used economic incentive to pressure foreign companies to do its bidding beyond the borders of China.

We also see a kind of voluntary or even willful definition and enforcement of digital borders by content producers and publishers. Sometimes, it is simply a case of managing copyright and distribution licenses. For example, when you upload content to platforms like YouTube, you can choose to include or exclude users in certain jurisdictions from viewing the content. On a recent stopover through Paris, I discovered that one of my favorite shows disappeared from my Netflix account because Netflix does not have distribution rights for that show in Europe.

On that same stopover, I tried to read an article on the Los Angeles Times website, only to discover that the newspaper has chosen to cut off access to users in most European Union countries. This was the publisher’s response to the launch of the GDPR, the European Union’s comprehensive legislation for online privacy protection and data management. The LA Times decided that it could not comply with the legislation and maintain its current business model, so they blocked themselves from much of Europe. The European Union did not set up a Great Firewall like China has, but it seems that the GDPR is starting to have similar effects of creating hard borders in the sea of online content.

Terra Nullius

I came of age online at a time of utopian ambitions. For many, the Internet and the so-called cyberspace were terra nullius, a no-man’s land belonging to everyone and to no one. Netizens would have a kind of digital allmansrätt, the Nordic everyman’s right to roam from hyperlink to hyperlink, crossing borders seamlessly, hindered only by the speed of our ethernet connections. Since that heady, idealistic time, we have seen an enclosure of the digital commons. Nation-states have enforced their borders online in different ways, first with defensive firewalls and traditional censorship. And now, we see a new form of offensive power, the power to project their policies beyond their borders by pressuring companies to do the work of authoritarians. The result is diminished usability and freedom for all.

There are signs that people working in design and technology are engaging on these issues. Earlier this year, the New York Times reported on an open letter signed by hundreds of Google employees that protested the tech giant’s work on a search engine that censors content banned by the Chinese government. Ethical questions like whether or not to work on a censored search engine to expand in a potentially lucrative market do not exist in isolation. It is not just a question about the ethics of censorship. This requires us to look at a range of issues from transparency and democracy in the workplace to strategies and imperatives to maximize shareholder value in corporate governance. We also need to look at and debate politics and policies.

Designing tools and technology for the public is inherently political. And even more so when we are designing at a scale that crosses national borders and legal jurisdictions. As practitioners, we need to continuously educate ourselves on these issues, engage in debate, and take collective action when appropriate.