Issue 4: Bodies and Borders

Manzini, Social Innovation, and Designing Democracy

A Proposal for Collaboration as a Form of Resistance

Since the 60s, but especially in the wake of the Syrian refugee crisis and the crisis of Western democracies in the 2010s, traditional designers are finding themselves operating outside of their traditional craft and widening the scope of how they serve society. Designers (technologists, artists, service designers, sociologists, and other related professionals) are stepping up to fashion not only artifacts and products, but entire self-sustaining ecosystems where people can collaborate, think, and act together. They are designing for social innovation.

Ezio Manzini, a leading thinker in social innovation design practice, founder of the Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability (DESIS) Network, and the author of Design, When Everybody Designs, observes that social innovation projects that create mutually beneficial systems for immigrants and Europeans can help Europe sustain the influx of immigrants and at the same time create a stronger, more resilient Europe. He proposes that, if these practices are widely adopted, Europe will have the capacity to resist political involutions, fascist movements, and other such contemporary threats to its democratic bodies. Furthermore, he believes that as designers for social innovation we can play a role in reviving the democratic bodies that are currently under threat by populist (Neo-fascist) movements in all western democracies, not just ones in Europe. He invites us to create new sociopolitical bodies and support existing ones in order to help people break the silos that the current failing systems have created.

Ezio Manzini, a leading thinker in social innovation design practice, founder of the Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability (DESIS) Network, and the author of Design, When Everybody Designs, observes that social innovation projects that create mutually beneficial systems for immigrants and Europeans can help Europe sustain the influx of immigrants and at the same time create a stronger, more resilient Europe. He proposes that, if these practices are widely adopted, Europe will have the capacity to resist political involutions, fascist movements, and other such contemporary threats to its democratic bodies. Furthermore, he believes that as designers for social innovation we can play a role in reviving the democratic bodies that are currently under threat by populist (Neo-fascist) movements in all western democracies, not just ones in Europe. He invites us to create new sociopolitical bodies and support existing ones in order to help people break the silos that the current failing systems have created.

I’ll have whatever Manzini is having.

Preface

The first part of this article is about bodies of refugees that have pushed Europe to adopt methods of collaborative inclusion. Manzini presents successful and inspiring collaborations between European citizens and refugees. These collaborations help forge a healthy social fabric and strengthen democratic rituals.

Part II shifts focus to democratic bodies. Manzini observes that these bodies—political parties and other political associations (political clubs, NGOs, PACs)—are being threatened by the hyperconnectivity of internet bubbles that force an overly simplistic understanding of democracy. The result is a lack of the types of conversations that allow democracies to stay resilient and have a diversity of ideas. Manzini, influenced by the ideas of Victor Margolin, suggests that technologists, designers, and many other professionals who might, as Manzini puts it, “make things happen,” can use social innovation design practices to help fashion new sociopolitical bodies as alternatives to the internet bubbles that have resulted in this crisis of democracy. In other words, he invites us to use our skills not only in the ‘politics of everyday life’ but in political life itself. Designers can help citizens and politicians redesign arenas for healthy discourse and a lively civic life.

But first, what is social innovation design practice?

Before I address bodies of immigrants and democratic bodies, I would like to contextualize social innovation and how it can create a resilient, sustainable society.

The term social innovation has been around since the 1960s, but did not become widely used until about two decades ago. The implementation of social innovation practices as we recognize the term today became more prominent in design communities fairly recently as the need for better, more sustainable systems arose. People began to take note of the desertification of the overall natural and sociocultural environment; a marked reduction of biological and sociocultural diversity due to large production plants, standardization, large hierarchical systems, and other stratifications tied to outdated systems of social security, healthcare, welfare, food production, and education.

A redesign was needed.

In response to mainstream (archaic) systems, small islands of disruptive alternatives have begun to emerge. These groups of people have come together to organize food coops, financial coops, fair trade initiatives and so on, thereby replenishing the diversity in choices that people had in designing their lives. Expert designers began to help these groups and called it design for social innovation.

Manzini’s DESIS network defines social innovation as the following:

Social innovation can be seen as a process of change emerging from the creative re-combination of existing assets (social capital, historical heritage, traditional craftsmanship, accessible advanced technology) and aiming at achieving socially recognized goals in new ways. A kind of innovation driven by social demands rather than by the market and/or autonomous techno-scientific research, and generated more by the actors involved than by specialists.

In social innovation projects everyone is a designer, including the main beneficiaries of the service or product. When the expert designers initially brought in to architect a project move on, the remaining social actors are left with a structure upon which they can continue to design and improve. What’s great about this approach is that the people who are being designed for are not seen as passive recipients of services but as capable co-creators and collaborators that can continue to design on their own. This is what makes it sustainable design.

Here is a classic example of successful social innovation:

Collaborative Welfare

In Italy, as well as many other European nations, older populations are starting to outnumber younger ones. Even if eldercare subsidized by a top-down government initiative was a given, there simply aren’t enough young people to hire as caretakers. A proposed solution to this problem is a network comprised of elderly people of different ages with different degrees of ability and energy. Seniors all receive some degree of aid from social workers or volunteers, but those who are more active can help those who are older or more limited, thereby relieving the workload on the limited amount of social workers.

Social innovation projects are continuing to rebuild places that existing dinosaur systems (Amazon, Microsoft, etc.) have stomped out. For example, farmers’ markets and food coops are socially innovative alternatives to giant corporate grocery stores that have replaced the ‘mom and pop’ stores of the past.

Parallels can also be seen in response to the ways corporate supermarkets and internet monarchs like Facebook limit our choices. Islands of open-source—more democratic, alternative platforms—are starting to emerge in the same way that farmers’ markets and locally sourced food coops came about.

Simply put, design for social innovation is design that triggers and supports social change. Manzini believes that these new ways of working and living together are creating stronger, more resilient communities and therefore stronger democracies. Partaking in these collaborative, hyperlocal, distributed systems is an active form of resistance to the old systems that no longer serve us.

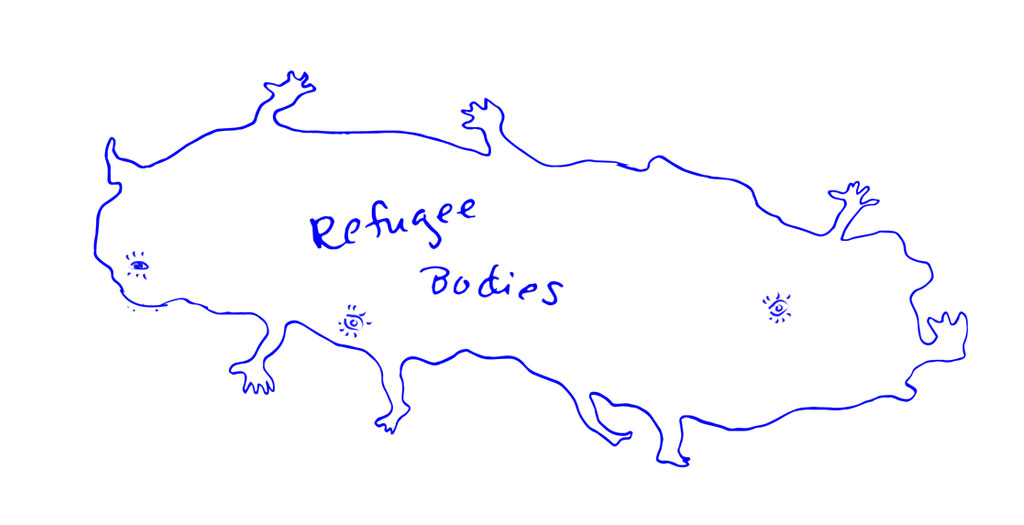

Refugee Bodies

The rise of populist sentiments in Europe are widely thought to be the result of an increasing socioeconomic gap. Sound familiar? But this does not seem to be the only factor. According to a study conducted by the Brookings Institution, “it is now evident that populism draws strength from public opposition to mass immigration, cultural liberalization, and the perceived surrender of national sovereignty to distant and unresponsive international bodies.”

With the influx of Syrian refugees to Europe starting in 2015 and continuing throughout the later half of the decade, Europe has continued to face a strain to its resources. In addition to exhausting the welfare system, a large influx of new urban dwellers has began to strain environmental and energy infrastructures. Concurrent with this strain, the European citizenry has increasingly adopted a Neo-fascist stance.

In her essay We Refugees, Hannah Arendt talks about forcibly displaced individuals, and how their placelessness and disposability in society takes a heavy toll on them. To allow people to remain “nobodies” is a way to “kill men without any bloodshed,” writes Arendt. The task of including displaced Syrian refugees in society, especially the European society of today, is as difficult as it is vital for the health of the newly forming European social fabric, infrastructure, and economy. Furthermore, it has become clear that it is no longer sustainable to serve refugees using a traditional, non-inclusive, top-down humanitarian approach.

Designers of all backgrounds (service designers, technologists, sociologists, business strategists, and other actors in the social innovation space) from all over the world have been asked to come up with ways to allow refugees to add to their local economies—and in doing so become integrated with their host societies. MIT Enterprise Forum Pan Arab’s Innovate for Refugees challenge prize, for instance, was a significant catalyst in generating some of the most effective designs integrating refugees not only in Europe but throughout the Middle East.

In his presentation at Parsons Verge Conference in 2017, Manzini was able to recount a number of successful social innovation projects carried out in Europe as well. In Germany, Refugees Welcome is a platform that gives refugees the choice to go into a home instead of a camp, matching German citizens’ spare rooms with refugees in need. In London, The Bike Project repairs abandoned bikes and offers them to asylum seekers, and trains refugees to repair bikes as well. In Italy a heavily depopulated village called Riace has invited migrants to live in existing empty houses and to start different kinds of craft, farming and management activities.

These projects have managed to grant refugees freedom of movement and build skill-sets and self-esteem while also allowing them to gain a sense of citizenship. At the same time, those with EU citizenship co-create value not only for themselves but for the whole community. Other social innovation projects with the aim of integrating refugees in the Middle East, North Africa and Canada have been met with success and can also be used as examples to reinforce Manzini’s point. The challenge for Europe, as Manzini says, is to see this integration not as a threat but as an opportunity.

Manzini argues that the immigration crisis in Europe is forcing Europeans to relearn the art of skilled collaboration that, according to sociologist Richard Sennett in his book Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation, Western society has lost as the result of isolating, overly competitive work cultures and cultural divides. Sennett calls for relearning the difficult kind of cooperation—cooperation with people we don’t know or don’t like yet. Can we think of the immigration crisis as a challenge to change our ways in the Western world? In the US we are not suffering an immigration crisis in the same way that Europe is, but the same populist sentiments are echoed.  All of the West is in some way dealing with similar issues of tribalism. Is this an opportunity to become more accepting of diversity and adopt a better philosophy and practice on how we create together? To “imagine how migration can become a driver of innovation towards a younger, dynamic, cosmopolitan and, at the end of the day, more resilient” society?

All of the West is in some way dealing with similar issues of tribalism. Is this an opportunity to become more accepting of diversity and adopt a better philosophy and practice on how we create together? To “imagine how migration can become a driver of innovation towards a younger, dynamic, cosmopolitan and, at the end of the day, more resilient” society?

Democratic Bodies

Through social innovation we are able to generate more choices with which to design our lives as drivers, hackers, educators, grocers, caretakers, farmers; functions in the ‘politics of everyday life.’ The term ‘politics of everyday life’ has been around since the 1930’s and refers to making a political difference through actions outside the political sphere. For example, one can ‘vote with one’s dollar’ at the grocery store by buying green products, thereby indirectly influencing the environmental policy that could come about as a result of a more ecologically conscious society. One might say that creating these new ways of living and working together is already in and of itself the act of designing for democracy. By virtue of creating more choices for ourselves we live in a more democratic ecosystem. While this is helpful, Manzini comes to the conclusion that in today’s political climate, acting only in the ‘politics of everyday life’ is not creating change fast enough. He urges designers and technologists—those of us who have the privilege to “make things happen”12 —to be design activists.

In his Design the Future presentation at Carnegie Mellon University in 2017, Manzini refers to the Victor Margolin’s work on designing for democracy and adds his own thoughts on how we as designers (again, ‘designers’ is a loose definition that encompasses many professionals in the social innovation and sustainability space) can speed up the trends in democratic designs and interventions. He invites designers to (1) fashion the right environments where complex sociopolitical systems can emerge and (2) to increase visibility and give voice to the groups of people who are already “practicing something that extremely relevant to democracy.”12 The goal is to design more and more environments where all social actors have the capability to resist through action and to feel empowered to do so when they see that they are not alone.

Manzini hypothesizes that making meaningful things happen as a form of resistance—or design as activism—is essential in designing better, more democratic futures. These are forms of resistance that not only say ‘no’ but propose a solution or at least produce a story that anticipates possible alternative futures.

One example of disruptive and inspiring collaboration that Manzini uses is community gardening here in New York City. He observes that the gardening communities exemplify the type of collaboration that is lacking in our current internet bubble of hyperconnectivity—they demonstrate the ability of people to have trust and conversations, to decide on things together and balance opinions democratically.  This kind of hyperlocal activism is disruptive because it shows we can have the agency to propose new, complex bodies of organization. Mazini observes that designers (and other storytellers) tend to be instrumental in shining a spotlight on successful examples of these innovative associations. As a result, people are encouraged to build their own alternative collectives, start political action groups, run for office, etc.

This kind of hyperlocal activism is disruptive because it shows we can have the agency to propose new, complex bodies of organization. Mazini observes that designers (and other storytellers) tend to be instrumental in shining a spotlight on successful examples of these innovative associations. As a result, people are encouraged to build their own alternative collectives, start political action groups, run for office, etc.

In technology, we can observe open-source movements (Linux, for example) emerging as a form of resistance to existing methodologies (like Microsoft). These movements “constitute a new social and economic force and challenge existing products and conventional production methodologies.”

Recently MIT Media Lab research affiliate Cory Doctorow, a fellow at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, gave a lecture at Columbia Journalism School about subverting the “internet monarchs”16 like Facebook and Twitter to create more democratic, open internet “technical democracies.” In Beyond “I agree”: A democratic technology, without Big Tech he addresses issues of corruption and invites us to tame big tech by taking away its legal right to stop users from using tech how they want to. “Creating a structure and a temptation to behave monopolistically produces monopolies. Corruption doesn’t come from the evil in our souls but from the structures that make it easier to be wicked than to be virtuous.” Doctorow, just like Manzini, calls for a system in which everyone, not just the select few, can design.

A relevant thinker to add to the discussion is Elaine Scarry. In her book Thinking in an Emergency, Scarry warns against “surrender[ing] our power of resistance and our elementary forms of political responsibility” in response to “spurious invocations of emergency in the nuclear age.” She calls for preventative design in emergency planning to increase preparedness in turbulent times and combat unchecked executive power. “We collectively and thoughtfully address many forms of emergency conditions… in advance to make possible democratic, not dictatorial, responses.” The common theme seems to be that we aren’t designing enough and leaving it to the powers that may not always have everyone’s best interest in mind.

Designing for our system of governance

Ezio Manzini, much like Margolin, invites the audience of designers to help citizens find new levels of intervention in our current system of governance and perhaps even help fashion new democratic bodies or help existing ones compete against the dangerous populist movements that have become real competition in the past few years. “How is it that with… [such great examples of social innovation and collaboration in front of us]… we are still having to choose between the neoliberal and the New Traditionalist (Neo-fascist) regimes?” Manzini asks. He proposes that a well designed arena for conversations to flourish would result in a rich and complex system that is able to sustain a diversity of ideas and off resist simplistic, fascist movements. How do we design such an arena? Below are some examples of design for social innovation in civic tech that illustrate how social innovation practice can and is being used for such purposes.

1. Civic Tech

Civic tech (Sunlight Foundation, E-Estonia, vTaiwan to name a few) promise to shed light on what’s happening behind the walls of our institutions, encourage participation, and increase trust in the slow but resilient democratic processes.

When we redesign organizing platforms (resist.bot, a platform that helps community organizers reach constituents via text) and create ways for people to understand and track legislation (Councilmatic, a Civic Hall project) we partake in the civic tech movement. These types of projects can create environments in which existing organizers and political action committees can advocate for existing democratic bodies. For example, Democratic clubs of New York City, NGOs like the grassroots Indivisible Nation Brooklyn, or groups like the Democratic Socialists of America can reach more constituents, endorse and support more candidates like Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton who run in existing democratic bodies, namely the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party and its supporting organizations are democratic bodies that are under threat by the populist movements headed by actors like Donald Trump and the like.

In addition to designing innovative ways for old democratic bodies to sustain populist attack, we can also fashion new political bodies, such as labor unions, PACs, and new parties that have better, up-to-date political platforms. We can use our skills as professional software engineers, designers, strategists to assemble various social actors and enable them to do sustained political work.

2. Discussion platforms

Can we create socially innovative arenas for people to have complex dialogic interactions—interactions that require attention and responsiveness to other people—and debates, to agree and act together? It is this kind of collaborative exchange that, according to Manzini, allows complex political bodies to form. This contrasts with the monologic flow of simplistic social media exchanges. With more of this kind of design in tow, perhaps we can have better ways to converse and participate.

The goal is to compromise, establish trust, and work together towards common goals instead of encouraging silos for people who are scared of immigration, worried about their jobs, and happen to be very good at using Facebook to rally others. The social borders we put up when we build real and figurative walls between groups of people impede the ways in which cooperation can be learned and practiced. This type of atomism, exacerbated by social media, is what resulted in the need for social innovation practice in the first place.

For example, how is it that people were able to use a tool like Facebook to encourage the massacre of close to 9,000 Rohingya in Burma? This type of inadequate, crude communication created the walls that prevented diplomatic and dialogic exchanges on the edges of the two cultures. The Burmese and the Rohingya could have talked and collaborated despite their differences but the ease of simplistic monologic communication—hate speech and propaganda—left no space for empathetic listening and skilled diplomacy.

Can we create online discussion platforms as a resistance to Facebook and Twitter that are complex and inclusive, that allow for better quality communication? Can a digital platform really replace the richness and complexity of real face-to-face dialogue? Can such a platform be built with the tools available to us today? Is a digital platform enough? Do we trust designers and engineers to write the algorithms that will dictate what information appear higher up on our feeds? Is a social networking alternative like Mastadon a real solution to richer political discourse—a better democracy—or is it just a decentralized alternative to mainstream social media that allows for more privacy and customization? While more privacy and customization is important for the ‘politics of everyday life’ great social networking tools like Mastadon do not address the need for solidarity—nor do they aim to.

Both Manzini in his Design the Future talks, and Richard Sennett in his book Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation insist that if we are to have a lively democratic society we need real solidarity, which requires hard work and face-to-face conversations. Can we design platforms that enable face-to-face dialogue by funneling participants off the screen and into organized public events where more complexity and diversity of ideas can be generated?

Sennett and his colleagues tested out various collaboration platforms—this was about ten years ago—and found that they often don’t give enough attention to opinions that are not mainstream. The process—driven by algorithms and user-experience design—often marginalized the input and voice of the few. It appears as though even ten years later, digital democracies cannot replace real life assembly. Platforms that encourage such assembly seem the most promising.

More importantly, design thinkers like Manzini suggest that the success of conversations lies in creating small enough and connected enough communities where innovative design culture can thrive. Local and hyperconnected communities are easier to manage and present a more sustainable and inclusive way of living. This contrasts with our current condition of being atomized by large unwieldy systems. The danger of hyperconnected, small communities is that we can become quite insular. Manzini warns against this and emphasizes the need for what he calls cosmopolitan localism—the emerging scenario of the small, local, open and connected space.3 This is quite visionary, as nothing like this has been proposed to date.

This radical and promising notion of small, local, open and connected is the part I find most thrilling about Manzini’s work:

The four keywords so central to SLOC—small, local, open and connected—are meaningful because they are, at the same time, visionary, in the sense that they generate a vision of how society could be. By their very nature, they are comprehensible and easily understood by everybody, and they are also viable because they are supported by major drivers of change such as the complex relationships between globalisation and localisation, the power of the internet and the diffusion of new forms of organisation that makes it possible.

These four words are also important not just because they synthesise 20 years of study and case studies, but also because they clearly indicate that there is no hope for designing sustainable solutions without starting from the twin notions of local and of community. Conversely, there is no hope of implementing sustainable solutions without considering the greater framework of a globalized network society.

More radical ideas, questions and hopeful proposals for future design projects.

1. Design of software that taxes social media behemoths and other giant corporations, transferring revenue into a public fund to use for universal supplemental income and ecological improvements.

This isn’t my idea but I’ve taken to it. In the past few years, criticism of the exploitative nature of social media has become mainstream. Activists and advocates for more freedom to affect the technological systems that move us (Cybernetics conference here in New York and other forums) talk of designing ways that allow us to take control of the effects of social media on our lives.

The way I think about it, human resources are natural ones, which are being exploited by social media giants the same way that mining companies profit from taking natural resources out of land that belong to all its inhabitants. In the the same way Amazon harnessed the power of underemployed human populations in Seattle and continues to opportunistically exploit those workers despite some minimal improvements.  On the upside, Kazakh and Alaskan governments have begun to give part of the natural resource proceeds back to the people who live on the land. In the same vein it has been proposed that if social media companies are making money off of people’s time, there should be a way to compensate the people for seeing ads on their screens. What’s a fair percentage to give back?

On the upside, Kazakh and Alaskan governments have begun to give part of the natural resource proceeds back to the people who live on the land. In the same vein it has been proposed that if social media companies are making money off of people’s time, there should be a way to compensate the people for seeing ads on their screens. What’s a fair percentage to give back?

Concurrently, the idea of universal basic income is also gaining momentum. Can technologists work with legislators and ethicists to design some system or piece of software that fairly redistributes these funds? Will this type of social innovation be helpful in relieving some pressure to work-just-to-survive and carving out more time for family, civic engagement, and creative work? Would it be enough to supplement the deployment of renewable energy technologies in more locations? Is someone already working on something like this? (I have yet to find anything—but please let me know if you do.)

2. Civic Cafe or Modern-day Agora

This project was proposed by a team of participants in the NYC Service Design Jam in 2016. I don’t believe they pursued the project, but the idea stuck with me. The group imagined and detailed (rough prototype in the form of a skit with props) a hybrid space that is part civic and part private sector. In their version of the design, people could lounge, eat, hold meetings, take and teach classes, find out about civic hall meetings, and also get information on ways they can access government services like job training programs and tax preparation. What if it was a sort of modern-day agora with markets, concerts, exhibits, debates, daycare, green spaces? Probably these would be hyper local—one per neighborhood, like today’s farmers’ markets. Community board meetings could be hosted in these places to lower the entry-barrier for those who are new to local government participation. People might go to the space to buy produce and walk out having participated in a political debate. Imagine a future in which participation in various accessible degrees, not only voting every few years, is a normal, interesting, and beneficial monthly social activity.

3. IdeasCity

A year later, I was inspired by similar ideas at IdeasCity, a public event hosted by the New Museum here in New York City (as well as in many other cities). There, on Forum Stage, a series of workshops and debates were held about community building, the future of cities and public spaces, and of course the role of art and design in these projects. It is exciting to see where these collaborations between architects, designers, politicians and community organizers will lead and how public spaces will change over time.

Conclusion

“How should society be made different?” Richard Sennett writes in Together, describing a side-space event dubbed musée social (social museum) that took place in 1900 at the Paris Universal Exposition. The common enemy of this exhibit was the “surging capitalism of that era. They were convinced that raw capitalism could not produce a good quality of life for the masses.” However, the exhibitors on the very edge of this exhibition “did not dwell on the enemy in itself; this was a more adult forum than the modern curator’s transgressive exhibit meant to elicit howls of shock, horror, and rage. The Parisians have aptly named their project ‘The Social Question.’ How should society be made different? Socialist kitsch—happy workers singing as they prepare for a revolution—did not figure among the answers; nor had proposals for reform degraded into simple media labels like ‘fairness’ and ‘the big society’ (as the British Left and Right have recently branded their politicians). Exhibitors did agree on a common theme. ‘Solidarity’ was the buzzword in these rooms. Cooperation made sense of this connection: The German’s united labor union, the French Catholic voluntary organization, and the American workshop exhibited three ways to practice face-to-face collaboration.” (Sennett. Together. p. 36) The need for solidarity and cooperation was deemed paramount, regardless of political regime. This appears to hold true today.

In her interview with Krista Tippett, linguist and anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson also emphasizes the importance of cooperation and collaboration for the health of the social fabric and for human development. “Alas, one of the things we press on [children] is competition, because we have so much bought into the idea that competition is a law of nature and the only source of creativity. And incidentally, that is not a true biological fact. There is competition as part of the evolutionary process, but there is a tremendous amount of cooperation also involved, even at the cellular level.” In the Craftsman, Sennett writes about overly competitive work culture that atomizes workers, hindering cooperation. While neither Bateson or Sennett reject ‘raw capitalism’ in a simplistic way, they do warn us that we may have bought into the ideas too much. While a healthy amount of capitalism benefits social innovation projects, the ‘social’ in social innovation needs to be underscored and relied upon more heavily if it is to uphold and sustain democratic associations.

In Design, When Everybody Designs, Manzini lists “large production plants, standardisation, large hierarchical systems, and other simplifications” as the reasons for the “desertification of sociocultural and biological diversity.” One might conclude that the behaviors that disincentivize the prioritization of long-term human interests like a healthy ecology, educated populous, and healthy middle class—the same behaviors that reinforce short-term gains for the few—might be tossed out of the window or at least scaled back when we gradually redesign our increasingly more democratic ecosystem. But Manzini doesn’t state this so literally. It is not his style, and he seems to suggest the forces we are dealing with are much deeper than that. Maybe it is too simplistic to blame destructive forces of the late capitalist machine, or the proxy wars that lead to mass immigration, or even the poor communication platforms for our crises when the underlying culprit is the shortsightedness and human centrality that we have not learned to shake yet as a species. What Manzini does say, or rather ask, at the end of his book Design, When Everybody Designs is something more open-ended:

The idea that people’s individual interests could be “naturally” reconciled with those of society and of the planet may seem utopian. In effect it is, at least in part. However, many societies in the past, among their conventions, beliefs… did in fact hold behavioral norms that led individuals to choose to behave coherently in the short- and long-term interests of whole groups. Could something like this be proposed today?

Additional Resources

Here are just a few organizations that are trying to turn the tide:

Washington D.C.-based non profit organization that uses “civic technologies, open data, policy analysis and journalism to make our government and politics more accountable and transparent to all.”

An NYU entity that specializes in governance innovation.

Estonia’s online platform for civic engagement. This initiative has increased public participation and government transparency.

vTaiwan prototypes views of face-to-face public engagement encounters.

This Brooklyn-based organization specializes in civic tech. Councilmatic, a way to make city council meeting schedules available to the public, is one of the projects they created.