Issue 5: Reality?

Fairy Tales and The Necessity of Discomfort

Fairy Tales and The Necessity of Discomfort

By Marianne R. Petit

Illustrated by Marianne R. Petit

Will there be a happy ending? Or are we deluded, lonely ducks who will never become glorious swans? On fairy tales, personal storytelling and the necessity of discomfort.

“You see, the land of Grimm can be a harrowing place. But it is worth exploring. For, in life, it is in the darkest zones one finds the brightest beauty and the most luminous wisdom.”

– Adam Gidwitz, A Tale Dark and Grimm, Book 1

In 2010, I began a series of handmade books (accordion, carousel, pop-up) based on Heinrich Hoffman’s 1845 classic, Der Struwwelpeter. Hoffman, a noted German psychologist, wrote and illustrated his collection of morality tales for his son in response to what he perceived to be a lack of good children’s books. The book quickly became widely popular with both children and adults, in large part because the children in each of his stories encounter, both disturbingly and arguably hilariously, catastrophic consequences for their misbehavior.

For example, in “Shockheaded Peter” we learn that lack of personal grooming leads to tremendous unpopularity. In “The Story of Augustus Who Would Not Eat His Soup,” children are taught that if you do not eat what you are served, you will starve to death and die. In “The Dreadful Story of Pauline and the Matches,” careless children who play with matches burn to death. In “The Story of Little Suck-A-Thumb,” children who suck their thumbs get them chopped off by the evil Scissor Man who jumps through their window (“Snip! Snip!”). And finally, in “The Story of Flying Robert,” we are taught that if you go out in the rain, the wind will carry you away, no one will hear your screams and cries, and you will be lost. Forever. The End.

“There is a widespread refusal to let children know that the sources of much that goes wrong in life is due to our own very natures – the propensity of all men for acting aggressively, asocially, selfishly, out of anger, and anxiety. Instead, we want our children to believe that, inherently, all men are good. But children know that they are not always good; and often, even when they are, they would prefer not to be. This contradicts what they are told by their parents, and therefore makes the child a monster in his own eyes.”

– Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment

I describe my work as “exploring fairy tales, anatomical obsessions, and collective storytelling practices through mechanical books that combine animation and paper craft.” This statement seems to apply not only to my art practice but to my teaching as well, as this semester my course load includes “Fairy Tales for the 21st Century” (IMA) and “Collective Narrative” (ITP), in addition to “Introduction to Assistive Technology” (IMA).

At first glance, both the statement and the course load seem to be investigations into a series of unrelated subjects. However, the connections between them are strong, as storytelling (and the sharing of narratives) provides a powerful space necessary to reveal truths and our relationship to them.

Fairy tales and stories of magic have always served as a way to make sense of the unpredictabilities of the world around us. Fairy tales often have a moral, though sometimes not, and sometimes the moral is questionable at best. The structure of the fairy tale tends to involve a hero or heroine, a villain, and sometimes a friend who provides assistance or a gift. The world of the fairy tale typically lacks detail or rich description. The story almost always moves from event to event or action to action. Characters generally have no interior life, history, or psychology. Their motivations are simple: our hero/heroine is humble, kind, innocent, faithful, clever; our villain is evil.

Characters sometimes come in multiples or sets to make a point (see: three pigs, three bears, three fairies, twelve brothers, twelve dancing princesses, etc.), and often there is a difficult task or challenge. In “The Wild Swans,” Elisa (our heroine, and the youngest of twelve siblings) must break a spell and save the lives of her eleven brothers through silent and painful labor (knitting eleven sweaters from magic nettles without ever uttering a word.) She nearly loses her own life in the process.

And so, fairytales are often the antithesis of the “safe” stories we surround and protect our children and ourselves with. As children, we sense the world is not safe. We experience the unkindness of our peers. We recognize injustice even if we cannot articulate it. Fairy tales may practically warn us of the dangers that lurk in the woods, but more importantly, they often take deeper dilemmas and address them directly. They confront the realities of life and death. They address cruelty, fear, betrayal, isolation, rejection, and abandonment. In the process, they often show us that we can be courageous; face a difficult task alone; and, with steadfast determination, we can prevail.

Of course, in the Struwwelpeter, there are no happy endings for children. They lose their thumbs and float away. But these stories are invaluable too, because even as children we know that promises of happy endings aren’t necessarily true. That is why we laugh out loud when we read:

“The really ugly duckling heard these people, but he didn’t care. He knew that one day he would probably grow up to be a swan and be bigger and look better than anything in the pond. Well, as turns out, he was just a really ugly duckling. And he grew up to be just a really ugly duck. The End.”

– Jon Scieszka, The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales

We laugh, not necessarily because we’re making fun of the duck, but rather because maybe we’re all a little worried that we are that deluded lonely duck who will never be a glorious swan.

Fairy tales allow us a place to process the world’s violence, injustice, and cruelty. But what of the child who learns of the brutality of the world not through fairy tales, but first hand? Left floating in the space of non-childhood, perhaps they learn the power and protection of silence along the way instead. Yet, sharing these stories is invaluable, as Roxane Gay writes in her extraordinary memoir Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body:

“I also share what I do of my story because I believe in the importance of sharing histories of violence. I am reticent to share my own history of violence, but that history informs so much of who I am, what I write, how I write. It informs how I move through the world. It informs how I love and allow myself to be loved. It informs everything.”

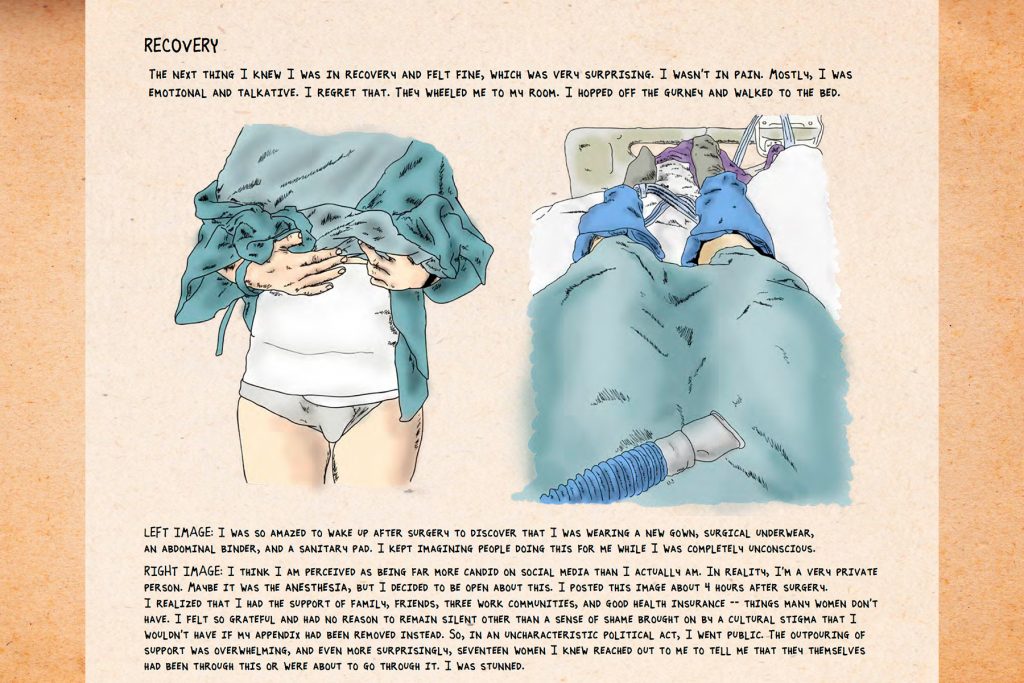

In 2017, I underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy, and upon waking up from surgery I felt surprisingly well. While I am typically rather private, I decided to be open about this. I had access to good health insurance, excellent medical care, and the support of three work communities—privileges many women don’t have. I felt no reason to remain silent other than a sense of shame brought on by a cultural stigma that I wouldn’t have had my appendix been removed instead. And so, in an uncharacteristically public political act, I posted an image of myself from the hospital on social media. The outpouring of support was overwhelming, but even more surprising, 17 women I knew reached out to tell me that they had been through the same thing, some only weeks earlier. I was stunned, and began to reflect on the stories that induce our silence and the fictions we present instead.

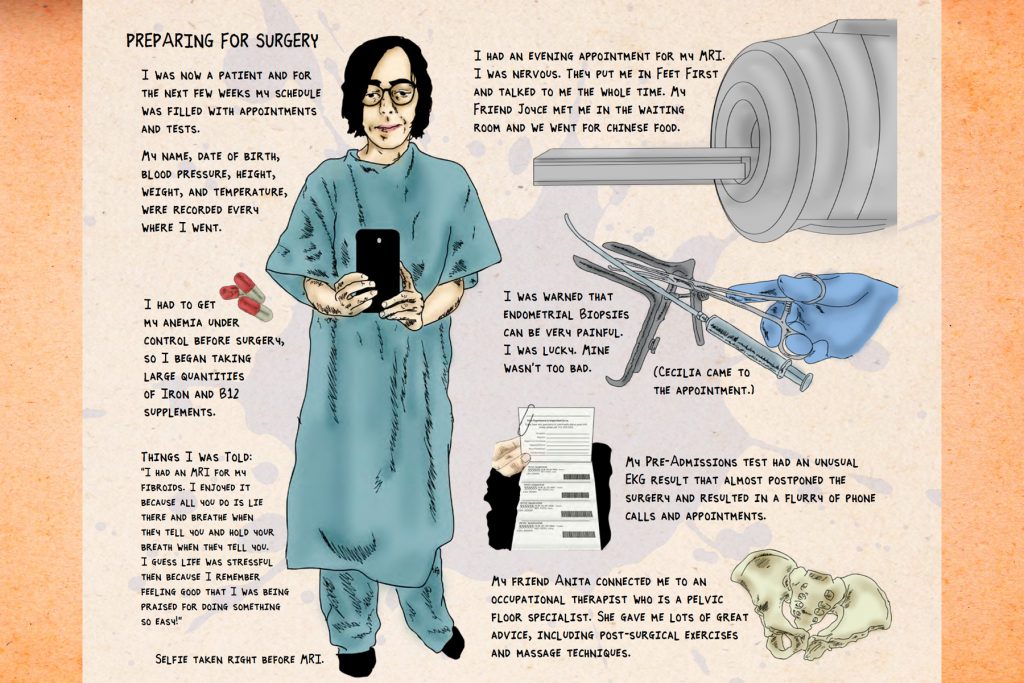

“Our Hysterectomies” (2018): Preparing for Surgery

“Our Hysterectomies” (2018): Surgical Recovery

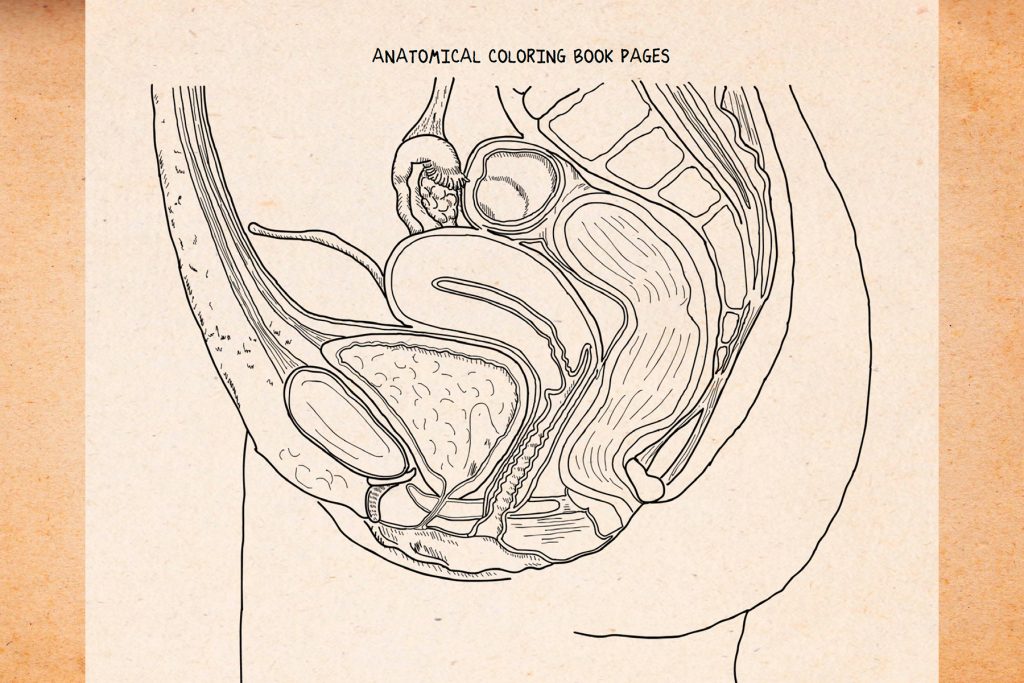

“Our Hysterectomies” (2018): Anatomical Coloring Book Pages

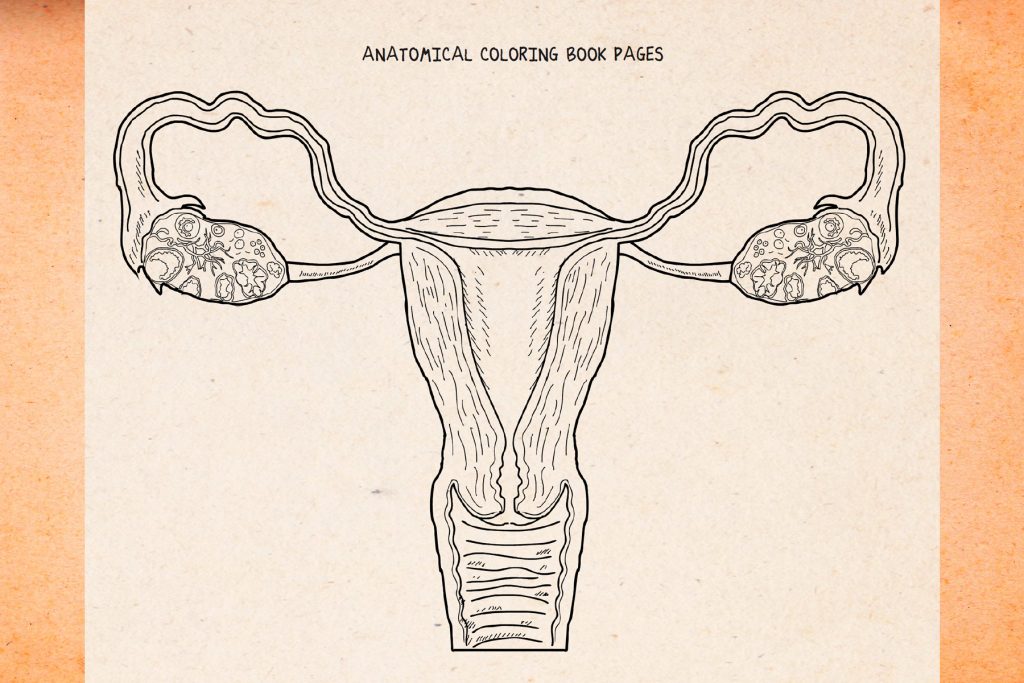

“Our Hysterectomies” (2018): Anatomical Coloring Book Pages

The result became an anthology entitled “Our Hysterectomies” (2018), an eBook containing the illustrated first-person accounts of 16 women who have had hysterectomies, oophorectomies, myomectomies, and more. Developed with an intention to increase awareness and support women’s access to healthcare services, the book was first made available as part of a fundraising campaign wherein all donations went directly to Planned Parenthood and all supporters received a copy of the eBook, regardless of donation amount. The book is now available online through numerous academic and medical humanities libraries.

It may seem a stretch to argue a connection between fairy tales and first-person accounts of loss or trauma. However, just as fairy tales provide a space for us to address and reflect on the difficulties of navigating a complex and often unkind world, the courage of another person’s truth can provide a similar space for allowing us to reflect upon and connect to our own story. These spaces (and these stories) are often uncomfortable, but this discomfort is vital and necessary.

In Sarah Schulman’s Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, she speaks directly to the necessity of this discomfort in speaking truth:

“We live with an idea of happiness that is based in other people’s diminishment. But we do not address this because we hold an idea of happiness that precludes being uncomfortable. Being uncomfortable is required in order to be accountable. But we currently live with a stupefying cultural value that makes being uncomfortable something to be avoided at all costs. Even at the cost of living a false life at the expense of others in an unjust society. We have a concept of happiness that excludes asking uncomfortable questions and saying things that are true but which might make us and others uncomfortable. Being uncomfortable or asking others to be uncomfortable is practically considered antisocial because the revelation of truth is tremendously dangerous to supremacy. As a result, we have a society in which the happiness of the privileged is based on never starting the process towards becoming accountable. If we want to transform the way we live, we will have to reposition being uncomfortable as a part of life, as part of the process of being a full human being, and as a personal responsibility.”

“There was an old lady who swallowed a cat”, Prototype Spread

I am currently working on several projects (to be launched 2019-2022), and consequently reflect daily on the power of shared narratives and the relevance of fairy tales to our current times. These projects are preliminary and include adaptations of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Wild Swans”; the Norwegian folk tale “Prince Lindworm”; a fractured version of “There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly”; a collection of 21st-Century Nursery Rhymes; and an illustrated anthology entitled On Murder, Forgiveness, and Perpetual Sorrow, which chronicles first-person accounts of individuals who have been affected by murder and its consequences.

These projects may seem unrelated, yet the threads connecting them gain clarity for me each day. Revealing ourselves through the stories we share and the stories we love can leave us feeling quite vulnerable. Yet, storytelling can give us the strength to hold the stories and feelings of others and the capacity to process our own discomfort and fears. Perhaps through this process we can collectively move to a more just and compassionate place. I hope so.

Marianne R. Petit is an artist and educator who explores fairy tales, anatomical obsessions, and collective storytelling through mechanical books that combine animation and paper craft. Her artwork has appeared internationally in festivals and exhibitions, has been featured in publications such as Hyperallergic, Make, Wired, and broadcast on IFC and PBS. Her movable books can be found in numerous collections including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the British Library, the Boston Library, as well as numerous University and private collections. | mariannerpetit.com