Issue 6: Old / New / Next

Cyberspace Trailblazers: Women of the Early Internet in NYC

New York City is one of the largest internet development communities in the world…How did this happen? I think it goes back to 1979 when Red Burns opened ITP (the Interactive Telecommunications Program) at NYU. This program has turned out so many important people in the Internet community. And the interesting thing to me is it started in an art school, The Tisch School of the Arts… I think still to this day that defines the distinguishing characteristic of the Internet Community in New York.”

Fred Wilson, Union Square Ventures

Introduction

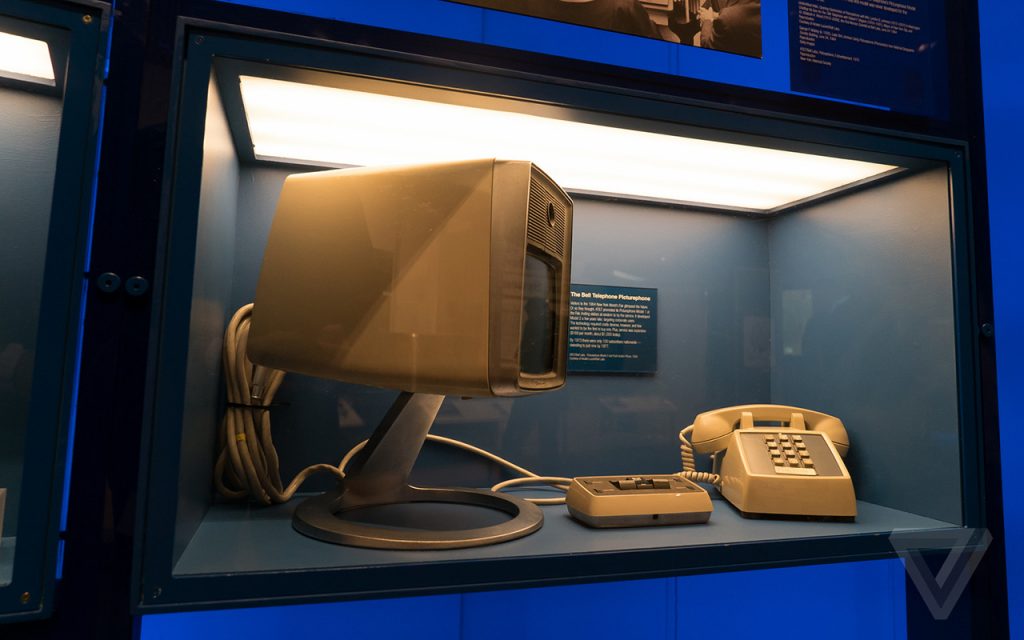

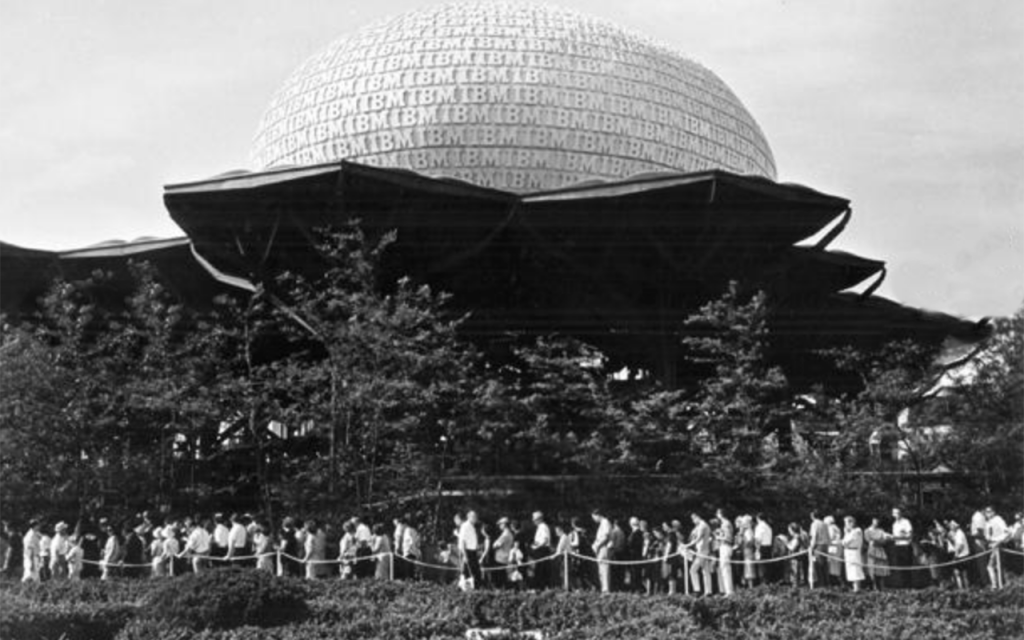

In 1964, an eight-year-old girl named Stacy Horn was one of the 50 million people who took a trip to Queens, New York to attend the World’s Fair. The exposition presented an optimistic and exuberant vision of a future realized through technology. And the visitors were wowed. “Oh yeah, we’ll definitely use that,” was the general consensus of fair-goers when they saw the Bell Labs Picturephone (2). One of the most popular exhibits was “The Egg,” a technology-packed pavilion by IBM that featured cutting-edge devices such as the Selectric (an electric typewriter that compressed the whole keyboard into an interchangeable ball of fonts)(1) and an immersive theater experience complete with hydraulic lifts. Most significant for this story, however, was that the general public had the opportunity to interact with computers for the first time. And were given a punch card to prove it.

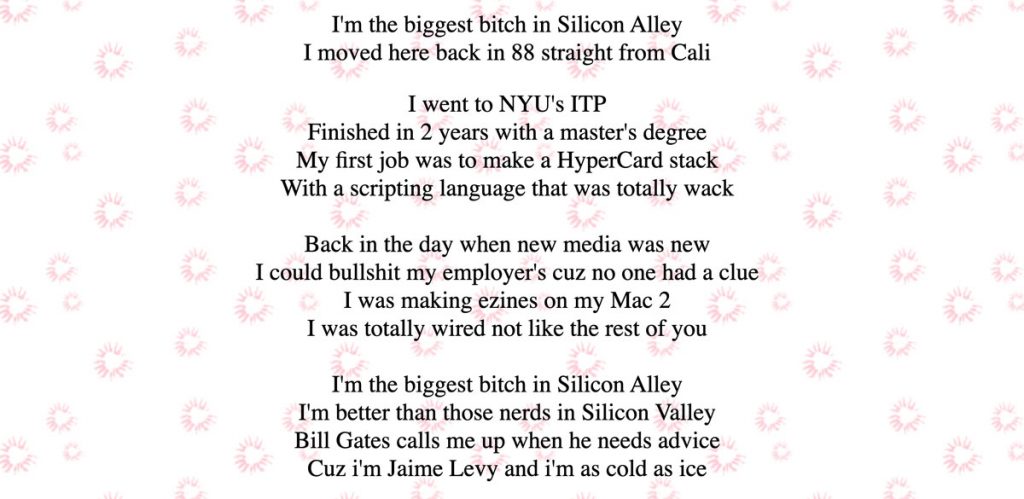

Thirty-four years later, in 1998, Stacy sponsored (and performed in) the Silicon Alley Talent Show, a fundraiser held for a new grant making organization called the Web Development Fund. The line-up of the First Annual Silicon Alley Talent Show read like an all-star roster of early internet pioneers in New York: Marisa Bowe was a judge, Jaime Levy rapped, Aliza Sherman played music––and it was all presided over by the woman known as the Godmother of Silicon Alley, Red Burns (who, at one point in the proceedings, a magician tried – and failed – to levitate). How exactly did we go electric typewriters in egg-shaped buildings, to now, walking around with the internet in our pockets? Part of the answer has to do with Stacy Horn and Red Burns, and other women, whose stories I will tell you. They were all pioneers who were instrumental in shaping the internet industry and culture in New York City.

History rarely follows a linear logic, or a clear path from A to B. Analogous to the internet itself, the Internet history recounted here follows multiple pathways that branch out into other pathways to connect each network of stories. What holds these stories together is the relationship between art and finance in New York, a city where these two worlds come together more potently than they do anywhere else in the country. That combination created an ecosystem distinct from other technology hubs, such as the Bay Area, Seattle and Boston(3). However, in its infancy, it wasn’t clear – or possible, with the available tools – to imagine that the internet could be a place for culture, commerce, or art and design. The Internet was still in the hands of engineers who were content in using black screens with neon green type. New York is the city where the change in all that started.

We’ll learn about this history by visiting four locations in lower Manhattan and hearing the stories of seven women who were cyberspace pioneers. If you’d like, you can take the map outside and use this article as a self-guided tour.

Stop 1 – ITP

“The closest thing to a spiritual advisor the new media scene has.”

Lisa Napoli, The New York Times On the Web, on Red Burns

We begin our tour at 721 Broadway at New York University’s (NYU) Tisch School of the Arts. Until 2019, the fourth floor of this building was home to the Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP). The story of ITP starts with a video camera, specifically the Sony Portapak, in the hands of Red Burns.

Red Burns – 1971

Godmother of Silicon Alley, Chair of ITP

ITP, NYU Tisch, 4th Floor

721 Broadway

If you turned on a TV in the late 1960’s, there were four available stations: ABC, CBS, NBC and one local channel. Then came three important events that, as Red would say, “was the difference that made a difference,” at least for this story. First, cable TV –with hundreds of channels– became widely available. Second, the Sony Portapak came to market. The Portapak was the first portable video camera, and a wonder at only 18 pounds. And third, in 1971, Red Burns picked up the Portapak for the first time:

“It was an epiphanal moment. People were now able to make their own documents and distribute them on cable television.These events introduced new avenues for disparate voices. Was this the beginning of a new kind of communication? What were the implications?”(4)

Red envisioned a world in which anyone could tell their own stories and broadcast them, independent of the TV networks. She imagined a future of widespread creativity and innovation.

Along with documentarian and journalist George Stoney, Red co-founded the Alternate Media Center (AMC) at NYU in 1971, to create large-scale telecommunications projects through research and field trials. The National Science Foundation awarded one of the AMC’s first grants for their project to connect senior citizens through a two-way television system –an idea reminiscent of the Bell Labs Picturephone and, of course, a harbinger of FaceTime.

Red, George and their AMC colleague Pat Enkyo O’Hara, were part of a group that successfully lobbied congress to pass legislation for setting aside part of the cable TV bandwidth for public use. They imagined these public frequencies –which became known as public access TV– as a place where people could have conversations, access community records, and publish personal stories(5). Their vision sounds a lot like what the internet would eventually become.

In the late 1970’s, Martin Elton, a professor of telecommunications policy at NYU, joined the AMC. Around this time, Red proposed what would become ITP to David Oppenheim, then the Dean of the School of the Arts (it was renamed Tisch School of the Arts in 1982(6)). The initial directive of the program was to train students in the technologies and methods used in the AMC field work. Elton was the first chair in 1979, followed by Mitchell Moss of NYU’s School for Public Administration in 1981. Red became chair in 1983, a position she held until 2010(7). Pat Enkyo O’Hara joined as full-time faculty and created the “communication lab” core requirements, as well as teaching portable video and editing.

ITP started with a class of 20 students and grew to 220 students a year, all on a single floor of Tisch – a permanent hive of spontaneity, experimentation, collaboration, and imagination with a hands-on people-centered approach that embraced failure. In Red’s words: “The program’s focus on interactivity is asking us to reimagine the new technologies as the verb not the noun. Technology is not value-free. It takes on the values of its designers.”(8)

Red had a knack for bringing people from different backgrounds together, fostering collaboration and innovation. As the former President of NYU, John Sexton said, “Red Burns is a force of nature. Almost a force stronger than nature.”(9) To me, what is more impressive than her accomplishments, awards, and accolades (of which there were many) is the way people remember her. She believed in people, sometimes in a way they had never believed in themselves(10). She understood how to spark collaborative relationships between people from different backgrounds.

Red impacted the burgeoning new media scene in New York through her own social-impact-focused work and her mentorship. She challenged the status quo and asked tough questions about technology. But most notably, she changed this field through the ITP program itself. Since its founding, ITP has graduated more than 3,000 creative technologists. As we’ll see at our later stops, several of these alumni were central figures in the tech ecosystem in New York City in the 1980’s and 1990’s.

Stop 2 – @Cafe

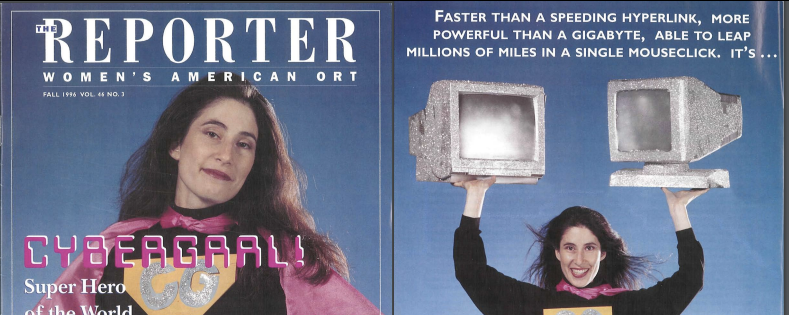

“Faster than a speeding hyperlink, more powerful than a gigabyte, able to leap millions of miles in a single mouse click. It’s… CYBERGRRL!”

The Reporter profiling Aliza Sherman in 1996(11)

Nestled in the East Village, the vegan restaurant that currently occupies 12 St. Marks Place is the former site of @Cafe, one of the first internet cafes in New York City(12). Take a look inside – where there are now tables with couples and friends eating garlicky kale burritos, imagine boxy beige monitors with glowing screens lining the wall.

Aliza Sherman -1995

Cybergrrl, founder of Webgrrls

@Cafe

12 St. Marks Place

One March day in 1995, Aliza Sherman sat in this cafe waiting to meet her first Webgrrl. A year earlier, she had accidentally started a women’s networking group online and was now about to meet one of the members in person for the first time. Leading up to the 1990’s, women were more likely to be familiar with operating computers than men because of the clerical and data processing roles that were available to them in office settings(13). This is how Aliza Sherman became interested in computers. She used her first computer working as a temp at a bank while pursuing a writing career.

Aliza eventually bought her own computer and became more and more involved with a little help from her friends: one showing her how to connect to dial-up, another telling her about Echo and Women’s Wire, two online discussion groups. She joined both, but eventually quit Echo and was surprised when she got a call from the creator of Echo herself, Stacy Horn: “We’re trying to get more women online so I wanted to ask why you quit,” Aliza remembers her saying(14). At this time, only 18% of Americans had internet at home (15)and women were significantly less likely to be online than men(16) –some estimates say that women made up only 10% of internet users(17). Then, as now, it was common for women to be harassed online. Women like Stacy Horn and Aliza Sherman worked passionately and tirelessly to make the internet a safe and welcoming place.

Through forums like these, Aliza became a leader online. When she saw a billboard advertising a $10 HTML class, she enrolled and designed her first website. Because she didn’t feel safe revealing her identity online, she created an avatar she called Cybergrrl, complete with a cape and logo. Aliza started scavenging the Web for other sites made by women like herself and highlighted them on her homepage, giving them the name, Webgrrls. Her site started gaining momentum, so in March of 1995 she posted a message on her page: “If you’re a Webgrrl in NYC, let’s meet up.” That’s how she found herself in @Cafe waiting for the first Webgrrl to show up, wondering what a Webgrrl would be like.

The first Webgrrl turned out to be singer-composer-artist Phoebe Legere. After that initial meetup, Aliza was a woman with a mission. She turned Webgrrls into a global network of women on the internet that supported each other in learning about technology, building skills, mentoring each other and starting businesses through a hybrid approach of online-offline meetups. In 1995, Aliza was named by Newsweek as one of the Top 50 People Who Matter Most on the Internet. She was one of only three women on the list(18). By 2000, Webgrrls had more than 30,000 members(19).

Theresa Duncan – 1995

Video game designer, creator of Chop Suey

East Village

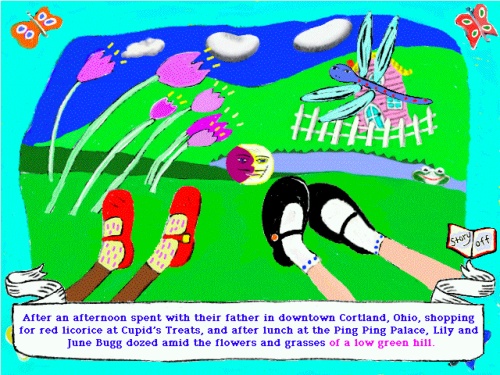

During the 1990s, you would also find Theresa Duncan in the East Village. She was a video game designer, most well known for an interactive, narrative-based game called Chop Suey. In Chop Suey, two young girls explore the streets of a fluorescent city, their adventures narrated by the writer David Sedaris. Players can click on different locations on a winding map and are taken inside locales, including a Chinese restaurant, a backyard picnic and a circus tent to see animations of stories narrated with text and sound.

Chop Suey was one of the first video games targeted towards girls. The Girls’ Game Movement featured games that rejected traditional gender roles in play, and aimed to make fun, high-quality computer games for girls that went beyond simply putting a pink bow on PAC-MAN(20). Chop Suey was chosen by Entertainment Weekly as the 1995 CD-ROM of the year(21). Although the movement died out in the late 90’s, many of the founding mothers –Brenda Laurel, danah boyd, Justine Cassell, and Tracy Fullerton––have continued to make significant contributions to the world of tech.

Tragically, Theresa took her own life in 2007. Even after her death, the press continued to focus on her looks and clothes before her work, referring to her using terms such as the “pretty-girl” of video games and “diva-ish.” Journalist and former Rookie Mag contributor Amy Rose Spiegel wrote: “[Theresa] knew that even while trying to espouse freedom from gendered ideals within girl–media, people outside of it are quick to appoint you an “It” girl – the awful designation that makes twins out of “female” and “object.”(22)

Theresa wanted to create “the most beautiful thing a 7-year-old has ever seen,”(23) but also believed that media and games should be rigorous, educational, and experiential: “I wanted [Chop Suey] to be a rich literary experience, so I tried to use words and ideas that children might not otherwise experience. People aren’t as critical of New Media as they are of cinema or traditional storytelling, but I think more should be expected of it.” (24)

You can wander the streets of Chop Suey yourself in the archived version hosted by Rhizome.

Stop 3 – FEED Magazine Office

225 Lafayette, Soho

Here we are at the front door of the Feed office, one of the first online magazines. Just down the block is the intersection of Houston and Broadway, the epicenter of Silicon Alley. At its height, this district even had its own newspaper, the Silicon Alley Reporter. Built on the backbone of the NYC art and media scene, but always in the shadow of the West Coast, it started as a group of young artists who got into tech to pay their rent. At first, they couldn’t believe they got paid to play with HTML and push the limits of what this new online medium was capable of doing.

But Silicon Alley quickly morphed into a conglomerate of companies with fake employees, auras fueled by wacky names and crazy parties, clocking out at 2am, overnight millionaires, CEO’s that constantly played video games, drinking and drugs in the office, massive turnover and burnout, and talk of IPOs. And, ironically, the work turned formulaic. The culture bred Freaks against the Suits. And finally, the smoke and mirrors were revealed to the world with the Dot Com Crash of 2000.

Jaime Levy – 1994

Creative Director, Word.com

Electronic Hollywood, Midtown

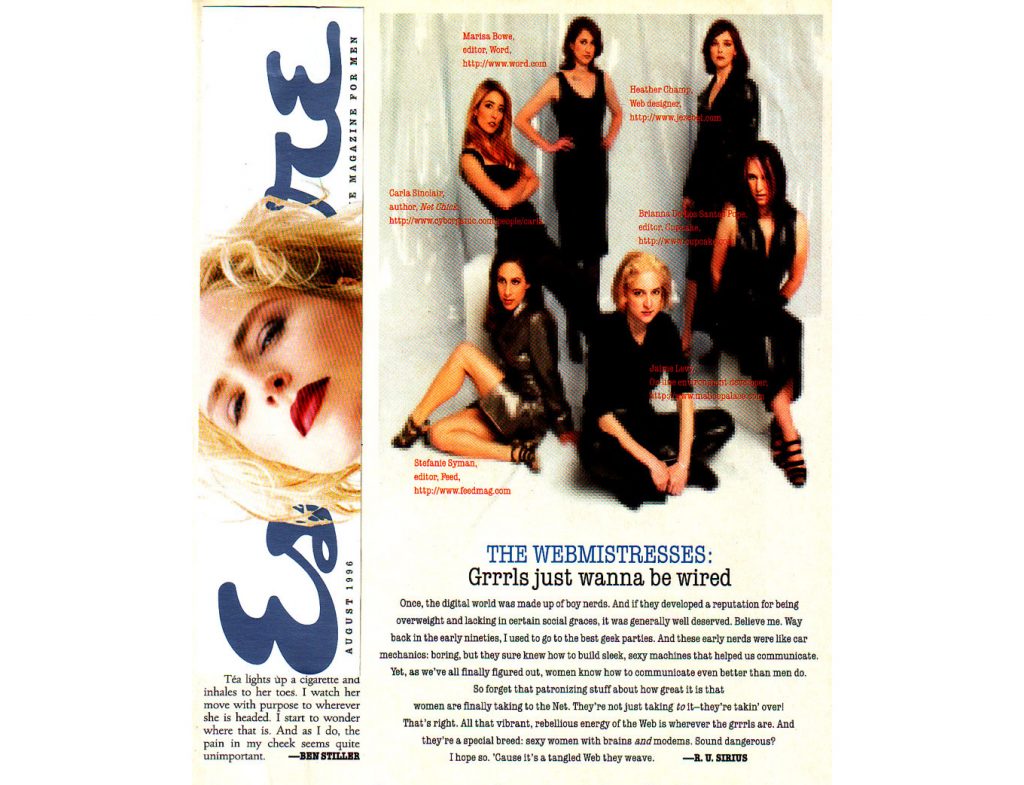

When Netscape launched in 1994, and The New York Times had to explain what an internet browser was to its readership, they used Word.com as the example of what a website is. One of the first internet magazines, and first multimedia e-magazines, Word.com was run by Jaime Levy and Editor-in-Chief, Marisa Bowe. As Creative Director, Jaime Levy, pushed ideas of the kind of platform a magazine could be on the internet. Word’s content was subversive and critical with a cyber girl-rocker aesthetic, obliterating both high and low culture at the same time. When there were only 14 million people who had an internet connection in the world,(25) Word.com had 100,000 readers a week.

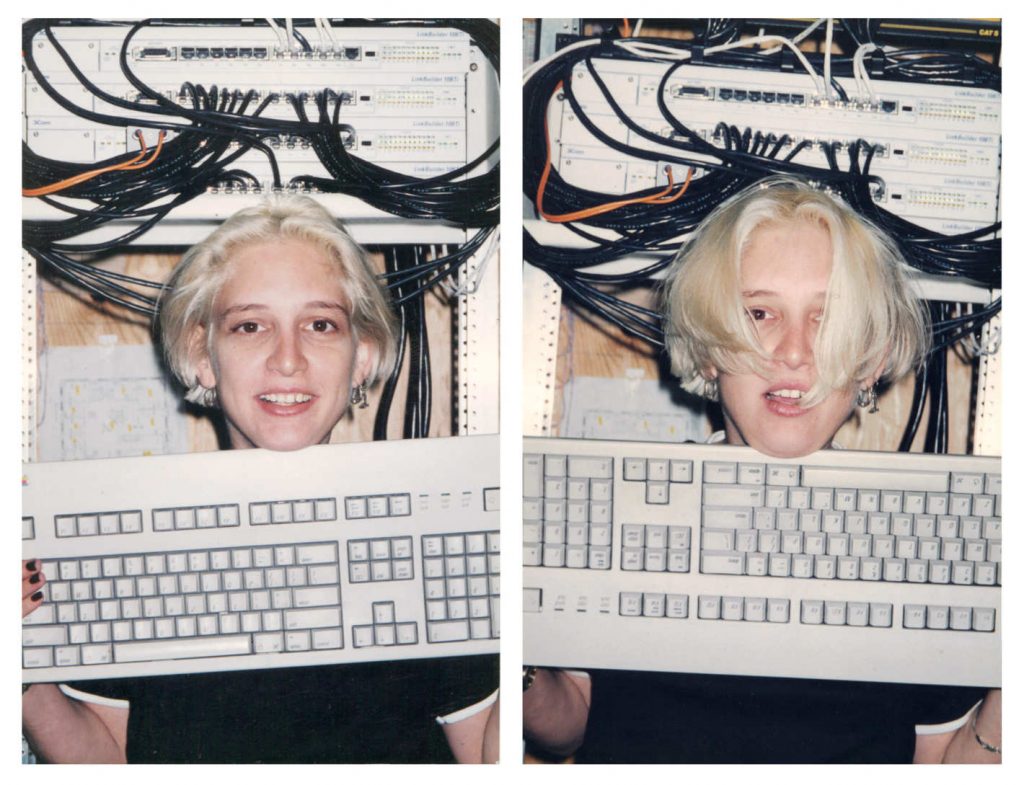

Titles such as “goddess of the electronic kingdom,” “creative genius” and “one of the hottest minds in cyberspace” were attached to Jaime Levy’s name. Levy got her start in e-zines when she began making and distributing a magazine called Cyber Rag on floppy disks as a student at ITP. If you were lucky, you might have been able to find a Cyber Rag floppy disk enclosed in an envelope posted to a telephone pole in the East Village.(26)

In a 1993 interview, Jaime explained her electronic magazines on a TV segment like this: “Basically you just buy this floppy disk – 6 bucks – put it in your computer…boom. If you hate it, take the files off, throw it away, you put your own files on it. It’s recyclable.”(27) Cyber Rag magazines included not only text but interactive graphics, sound and animations. This was a new kind of reading: “Interactive means you have some sort of control over your destination, how you wanna read your information, it’s not linear,” as Jaime explains.(28) She eventually turned her floppy disk magazines into a business called Electronic Hollywood.

Jaime achieved international fame when Billy Idol found copies of Cyber Rag in a Los Angeles bookstore and asked her to make an electronic press kit for his next album. When he released Cyberpunk, a special edition of the CD was accompanied by one of Jaime’s floppies that allowed fans to interactively explore the album concepts, song lyrics and digiart. (29) (30)

Marisa Bowe – 1994

a.k.a. Miss Outer Boro

Editor-In-Chief, Word.com

Midtown

In 1985, Marisa Bowe quit her job at PBS in Minneapolis and moved to New York City. She became involved with Paper Tiger Television, a non-profit video collective. When the group created Deep Dish TV, the first national satellite public access network, no one covered it except The Whole Earth Review. It was in that issue that Marisa Bowe read about TheWELL for the first time. The WELL, or Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link, was a pre-browser chat room that used a Bulletin Board System (BBS) system and had started California in association with the Whole Earth Review. (31)

JaimeLevy.com

Marisa had been in online chat rooms since the mid 70’s. Because her father’s job at Control Data Corporation required he use a computer, her family had one in the basement running PLATO, a pre-internet online network and the first computer-based education system. Marisa discovered that the platform was ideal for two key teenage activities: chatting and flirting.

Twenty years before the Millenials were born in the ’90s, Marisa was a digital native. But as a self-proclaimed “Ramones gal,” Marisa didn’t enjoy chatting with the Deadheads on The WELL over in California. Around this time, she found out about Echo after reading an article in the New York Times Magazine, and as Marisa says, “logged on and four years later looked up.”(32) By then, she was a minor celebrity in this tiny, but growing world.

During the early 1990s, few people were interested in the internet because there was no status associated with it. But Echo users understood even then, that this virtual world was ruled by a new attention economy, driven by the brilliance and humor people brought to a stripped-down medium. Marisa described Echo’s environment as uncanny in the way it afforded personal connection, “Some people you could just feel their psychic energy online.”(33) There were no ads or notifications. All you had was the scrolling text, black empty space behind it and your imagination.

When Jaime Levy was brought on to Word.com, she told editor Jonathan Van Meter that he should interview Marisa for the managing editor position. Marisa Bowe had never worked in magazine publishing, let alone online magazines, but no one else had either. As Marisa Bowe describes, in a similar way to so many others I spoke to about on their roles in Silicon Alley – her time on Echo and in TV had unknowingly perfectly prepared her, “I was in the right place at the right time. The screwing around I’d done online was now a skill. As one of the few people around NYC who had a smattering of both art/lit and internet, I was offered a job as a webzine editor. It turned out that I couldn’t have possibly planned a better résumé, because everything I knew how to do was part of “multimedia.”(34)

The Word team, including designer Yoshi Sodeoka, programmer Ranjit Bhatnagar and game designer Eric Zimmerman (now a professor at NYU’s Game Center, which grew out of ITP), pushed what Java, Quicktime, Flash, RealAudio and Shockwave could do by creating interactive media.(35) SissyFight was one of their most influential projects. The Word team wanted to create a new world for their readers, but with a subversive digital feminist spin. They decided to make a game that looked innocent but wasn’t: girls on a playground turned out to be the perfect subject. SissyFight was groundbreaking in terms of its technical achievements and content, but the team considered its biggest success making an online tool that a community remixed and made their own. For example, there was a player who portrayed himself as a reporter, interviewing the top players in a separate game room, and group of players that drew high-res versions of their avatars and then organized an online prom.

When asked about being a woman working in NYC tech at this time, Marisa shrugs off executives watching porn in their offices (“I just thought they were stupid”) but describes a certain awareness and pressure being in her position as a woman. She realized there was only room for one woman to be the cool cyberwoman, the internet’s version of the female art-rocker: “there are only a limited number of people who get quoted [in newspapers] and even fewer when you are a woman,” she explained.(36)

Marisa describes this time as fun, so much fun that she barely left the office for two years. She believed that the web could be as artistic as any other medium. But knowing the history of television and public access cable, she also realized that the internet would become dominated by advertising and that big corporations would run it.(37) Word was bought three years after its launch by the Zapata Corporation and closed two years after that in 2000.

Stefanie Syman -1996

225 Lafayette, Soho

Co-Founder, Feed Magazine

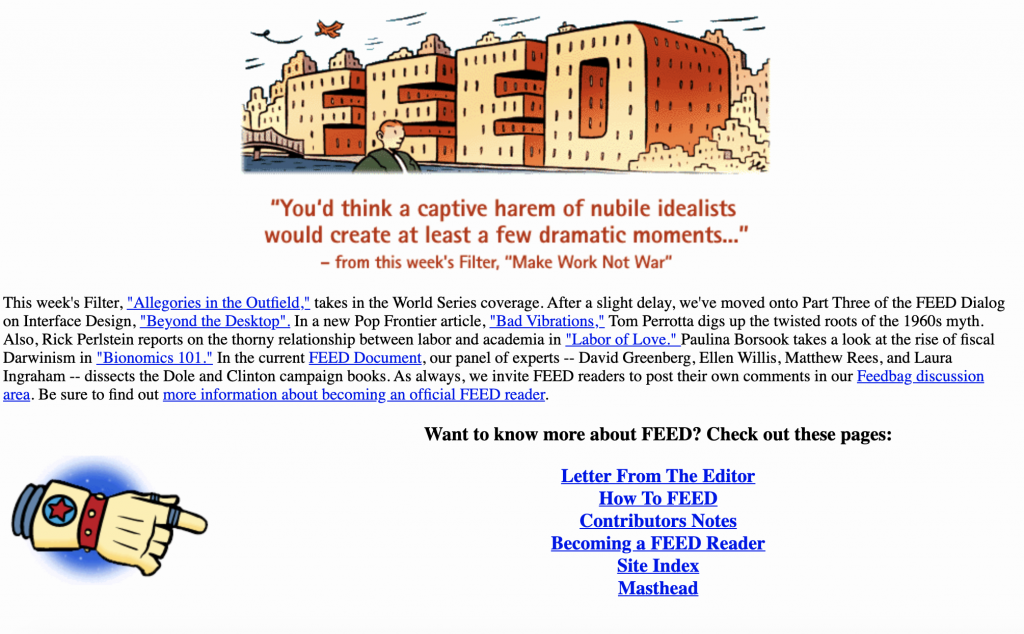

In 1996, Stefanie Syman and Steven Johnson launched Feed Magazine, an e-magazine focused on media criticism and editorials. “Cyberspace for grown-ups,” The Economist called it.(38)

Stefanie, a freelance technology writer with a Philosophy degree from Yale, was introduced to Steven through a mutual friend: “Hey, you both have email, you should be email buddies,” was the reasoning for the introduction. “That is how few people were online in any way,” recalls Stefanie.(39) Steven was also a technology writer, working for The Guardian. Six months later, after asking their aspiring writer friends for articles and hacking together HTML code to create a decent layout, they launched Feed.

In the beginning, all of Feed Magazine fit on two floppy discs. Constantly experimenting, they added commenting abilities early on and ran features such as dialogues with “thinkers” that took place over longer periods of time. Many of those aspiring writers from the first few issues are now well-known journalists, authors and critics.(40)

The Feed team believed that the internet wasn’t just a place for lists, but also a place for thoughtful writing. They hoped to balance out the West Coast tech idealism –epitomized in their minds by Wired, which had launched three years earlier 1993– with a New York sensibility and critical yet enthusiastic attitude towards technology.(41) In 1999, Newsweek named Feed one of the top websites and the magazine received Webby Award nominations in 1998 and 1999.(42) Five years after it started, Feed merged with Suck.com, and renamed itself Automatic Media. Automatic Media folded in 2001, another casualty of the dot com bust.

Stop 4 – Echo

“Echo has the highest population of women in cyberspace. And none of them will give you the time of day”

ECHO website banner (43)

Stacy Horn – 1990

Founder of Echo

Perry Street, Greenwich Village

Perry Street is a lovely tree-lined street in Greenwich Village, where Stacy Horn lives, that young girl mentioned at the beginning of this article, who went to the World’s Fair in Queens. She is also the woman who started Echo and called Aliza Sherman out of the blue.

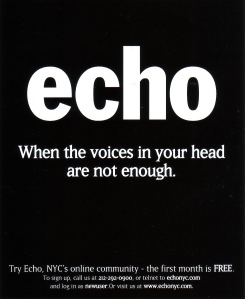

Echo was one of the first social networks online using what was called a Bulletin Board System (BBS). It was a pre-browser chat room that users dialed into and navigated using a text window. Visitors could select different conference topics ranging from “Angst” to “Don’t Panic” to “Zines,” similar to the subreddits of today. Echo was pulling in so much traffic at one point, that the City of New York had to rip up Perry Street to install more phone lines. Stacy’s neighbors were furious. But she promised them they would understand one day.

Stacy started Echo after falling in love with The WELL, when she created an account as part of a homework assignment at ITP. She had never encountered anything like it before. “The world was such that if you liked a book, you couldn’t just walk out your door and easily find people who had read it.,” Stacy puts it.(44) But suddenly, in cyberspace, you could.

Stacy Horn made it a point to create a place where women were welcome. Forty percent of Echo’s users were women, even as the internet became increasingly dominated by men. She made sure that every discussion topic had one male and one female moderator. And she discovered that if members met in person, they were much more likely to stay on Echo. So she arranged meetups at local bars, such as White Horse Inn and Art Bar. She also partnered with local organizations like Paper Magazine, The Village Voice, and The Whitney Museum, trading Echo conference rooms for advertising space in their publications. She wanted Echo to be intensely local.

In hearing Stacy describe this time, it’s clear that she understood what the future would look like before many other people did. But when asked if she was a visionary, she insisted, “No, it was so fun, anyone could see it was the future.”(45) This meant she also saw another side of that future. “The first thing you discover in addition to the fun, is that people fight. There’s sexual harassment…We had a Nazi.”(46) Unlike the internet of today, if people were having a fight online, she would ask that they meet in person with a moderator.

Stacy found the internet exciting because it was independent of time, space and, importantly, corporations. Nothing had ever been invented that could be described in quite that way. It was completely exhilarating. Stacy helped to host a New Year’s Eve Party at Grand Central Station called the First Night in Cyberspace in 1994/1995. The Echo team lined the balcony with dozens of computers, all hooked up to phone lines supplied by a provider for free, where party-goers could chat with another person on the other side of the world through a service called Internet Relay Chat. Grainy videos from that night show a middle-aged man in a tuxedo and top hat using his index fingers to pick out “H-a-p-p-y N-e-w Y-e-a-r.” Below, couples waltzed, and an orchestra played on the main terminal floor. For many people there, this magical setting was the first time they had ever been on the internet.

The end of the tour, for now

“While the current focus is on the Internet and it is exciting, the current version of it is just the beginning. Interacting with people anywhere in the world thousands of miles away is as easy as reaching someone across the street. But the possibilities are limitless.”

Red Burns, 1998, History of ITP

We understand ourselves and the world through the stories we tell. “Stories bump into stories and make new stories, changing even the way the world is,” says Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, co-founder of ITP.(47) There are many women I didn’t have the time or space to cover in this article. Even for the women who were included here, I could only tell a small piece of their story. There are many more stories of the past. And, even more intriguing, there are stories that are being made today and will be told forty years from now.

In talking with internet pioneers about New York in the 90’s, I am most struck by the spirit of invention and optimism for what the Internet would bring. While walking around the streets of New York today, I sometimes reflect on these stories of inter-disciplinary collaboration, DIY communities, radical support networks, interwoven and new identities with no need for conclusions and keep coming back to the same question: What would a feminist internet look like? I hope the current, and next, generation of technologists can answer that question for me, and for those women internet pioneers who made the space for that question to be asked in the first place.

There are many people that have helped with this article, but I would like to acknowledge a few here: Thank you to my partner on this project, Emma Rae Norton, ITP Camp and Kate Hartman for funding the first version of this research and especially to Claire L. Evans who wrote the book BroadBand: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet that inspired this research.

Footnotes

1. You can read more about the Selectric here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_Selectric_typewriter

2. O’Kane, Sean. Silicon City: New York’s Forgotten Role in the History of Computers. https://www.theverge.com/2015/11/13/9728640/silicon-city-ibm-new-york-historical-society-museum Published Nov 13, 2015.

3. Interview with Dr. Laine Nooney. June 10, 2019.

4. Burns, Red. A History of the Interactive Telecommunications Program. 1998.

5. Interview with George Agudow. September 30, 2019.

6. See for more details of the announcement: https://www.nytimes.com/1982/02/11/arts/7.5-million-tisch-gift-to-nyu.html

7. Burns, Red. A History of the Interactive Telecommunications Program. 1998.

8. Burns, Red. A History of the Interactive Telecommunications Program. 1998.

9. Red Burns ITP. 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r5QmNd-FpU4

10. Interview with Kate Swann. July 24, 2019.

10. Interview with Kate Swann. July 24, 2019.

11. Accessed through the Cybergrrl Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/originalcybergrrl/?tn-str=k*F

12. The hippest internet cafe of 1995. Vox. August 24, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iWssRVJgPqc&t=48s

13. Murphy, Michelle. Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2006: 55.

14. Fist Memories: Aliza Sherman. Women’s Internet History Project. http://womensinternethistory.org/first-memories-aliza-sherman/

15. File, Thom. Computer and Internet Use in the United States: Population Characteristics. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p20-569.pdf

16. Ono, HIroshi and Madeline Zavodny. Gender and the Internet. Social Science Quarterly. March 2003. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1540-6237.t01-1-8401007

17. https://qz.com/1309564/the-woman-who-taught-internet-strangers-to-actually-care-for-one-another/

18. The Net 50. Newsweek. December 24, 1995. https://www.newsweek.com/net-50-180208

19. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aliza_Sherman

20. Interview with Dr. Laine Nooney. June 10, 2019.

21. Sales, Nancy Jo. The Golden Suicides. Vanity Fair. January 2008. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/01/suicides200801

22. Spiegel, Amy Rose. I Think About This a Lot: The ‘90’s Computer Game Chop Suey. Feb 26, 2018. https://www.thecut.com/2018/02/i-think-about-this-a-lot-theresa-duncan-90s-computer-game-chop-suey.html

23. I Think About This a Lot: The ‘90’s Computer Game Chop Suey.

24. Munro, Cait. You Can Now Play Theresa Duncan’s Feminist CD-ROM Games at Rhizome. April 20, 2015. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/can-now-play-theresa-duncans-feminist-cd-rom-games-rhizome-289440

25. Rosner, Max, Hannah Ritchie and Esteban Oritz-Ospina. Internet. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/internet

26. Interview with George Agudow. September 30, 2019.

27. Jaime Levy and Electronic Publishing from “Life and Times” KCET in 1993. Jaimie Levy, Youtube. Uploaded June 29, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5aQCQ7-WYU

28. Jaime Levy and Electronic Publishing.

29. Tweet by Jaime Levy. April 25, 2019. https://twitter.com/BillyIdol/status/1152995686360571905

30. MTV Billy Idol. Vimeo. Uploaded by Jaime Levy. https://vimeo.com/237605446/7e2f3873c8

31. What is the Well? Well.com. https://www.well.com/about-2/

32. Interview with Marisa Bowe. October 6, 2019.

33. Interview with Marisa Bowe. October 6, 2019.

34. Bowe, Marisa. When I Grow Up. Vice. November 30, 2004. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vdbw5a/when-i-v11n3

35. See the Word archive at: http://deadword.com/

36. Interview with Marisa Bowe. October 6, 2019.

37. Silberman, Steve. Word Down: The End of an Era. Wired Magazine. March 11, 1998. https://www.wired.com/1998/03/word-down-the-end-of-an-era/

38. Media Kit, Feed Magazine. https://web.archive.org/web/20010202194700/http://feedmag.com/templates/media_kit.php3

39. McCullough, Brian. Co-Founder of Feed Magazine, Stefanie Syman. Internet History Podcast. December 6, 2015. http://www.internethistorypodcast.com/2015/12/co-founder-of-feed-magazine-stefanie-syman/#tabpanel6

40. https://conferences.oreilly.com/web2expo/webexsf2008/public/schedule/speaker/10190

41. Co-Founder of Feed Magazine, Stefanie Syman. Internet History Podcast.

42. Media Kit, Feed Magazine. https://web.archive.org/web/20010202194700/http://feedmag.com/templates/media_kit.php3

43. Evans, Claire L. The woman who taught the internet stranger to actually care for one another. Quartz. June 23, 2018. https://qz.com/1309564/the-woman-who-taught-internet-strangers-to-actually-care-for-one-another/

44. Interview with Stacy Horn. June 17, 2019.

45. Interview with Stacy Horn. June 17, 2019.

46. Interview with Stacy Horn. June 17, 2019.

47. Red Burns Memorial: Closing by Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara. Vimeo. Uploaded by ITP_NYU. https://vimeo.com/79002321