Issue 8: Disembodiment

Be THERE Now

Telepresence—the promise of a technology that will let us “be THERE now”—is an old dream with a new urgency. But when it feels like we’re really there, it’s easy to ignore the connections facilitating our “natural” experience: the systems that mediate our communication, the workers who build and maintain them, the ecosystems and laborers who supply the raw materials.

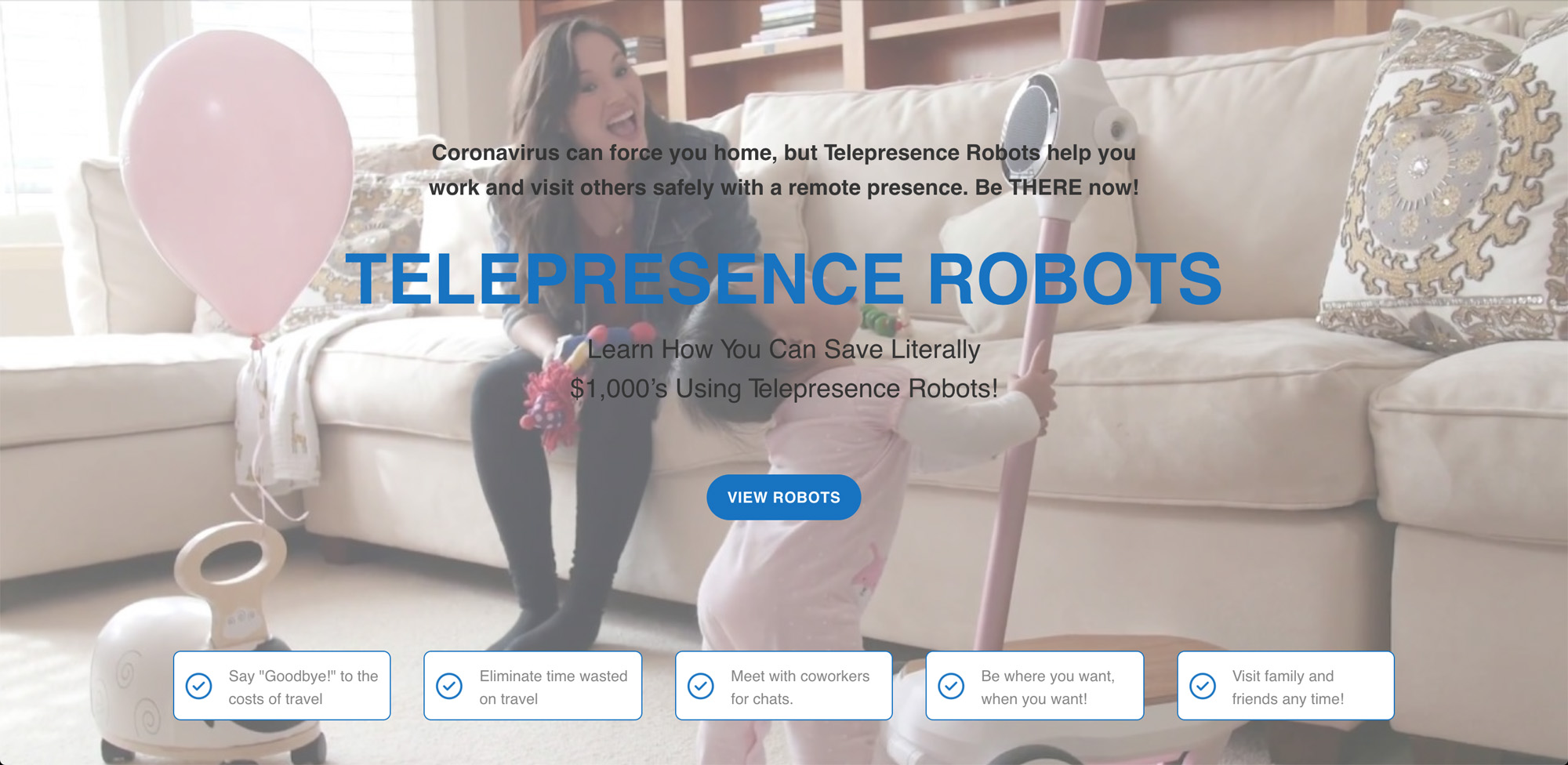

Screenshot of TelepresenceRobots.com’s homepage.

Screenshot of TelepresenceRobots.com’s homepage.

The homepage of TelepresenceRobots.com has big plans for my remote presence, now that COVID-19 has forced me home. One bullet point at a time, it describes the time and money I’ll save, the agency and access I’ll regain when I invest in a remote-controlled home for my consciousness. It will feel natural, too: I can “Be THERE now!” This promise is accompanied by a photograph of a comfortable living room where a wheeled platform sits in this scene of familial bliss. A warm glow radiates from the underside of the platform’s wood-toned base, and a millennial pink pole telescopes upward. A circular unit attached to the pole sits at eye level with the mother; I assume it’s some kind of camera and speaker, but its smooth surface lacks any indication of its function. This plastic-and-metal machine is surrounded by softness: plump upholstery, throw pillows, plush carpeting, a sheep, a balloon; all in shades of sanitary white and domestic pale pink. A toddler grasps the pole with both hands, mouth open and tongue protruding with joy. I can almost see the plume of germ particles leaving the toddler’s mouth. Just above their adorable butt is a friendly, rounded button with the words “VIEW ROBOTS.”

I’ve never seen a telepresence robot IRL, let alone in my living room. But the surreal scene is also familiar: it perfectly captures what it feels like to conduct large portions of my life over Zoom. Sometimes I feel like the toddler, gleefully gripping the cold metal as I talk to my loved ones; sometimes I’m more like the mother, mouth frozen in a stiff smile, eyes unfocused, unable to look past the poorly domesticated military-industrial-corporate technology standing in for the person on the other end. On bad days, I worry I might be most like the robot, struggling to arrange the unresponsive parts of myself into legible emotions, wedged awkwardly against the couch.

“Holographical Reality™ provides the ultimate communications experience by generating the three dimensional embodiment of the transmitted person to appear in the room for natural human communication.”

Credit: TelepresenceTech

Telepresence—the promise of a technology that will let us “be THERE now”—is an old dream with a new urgency. Telepresence isn’t a specific technology; it’s a narrative device, a sales pitch, an ideology, a myth. It promises an image so crisp, a connection so fast, a screen so diaphanous, that the whole assemblage melts away, leaving only, in the words accompanying this image from telepresencetech.com, “natural human communication.”

The last year of maintaining my close relationships through the bland, glitchy interfaces of business software has made me acutely aware of how far our current technologies are from fulfilling the promise of being there. At the same time, I’m all the more aware of the thoroughly embodied networks of resources, infrastructure, and labor—groceries, postal deliveries, power, trash collection—that sustain me. Someone has to be there by actually being there, and suffer the consequences of a now-risky physical proximity. That risk, of course, is not evenly distributed; it falls disproportionately on the Black and brown people whose labor has cared for the country, even as the country’s political and economic systems have utterly failed to care for them.

Mark Zuckerberg “visits” Puerto Rico in the aftermath of 2017’s devastating Hurricane Maria.

Credit: Screenshot of Facebook Live video, via The Verge

And yet, the myth of risk-free telepresence persists. “It feels like we’re really here in Puerto Rico,” says Mark Zuckerberg in a widely criticized 2017 promotional video for Facebook’s virtual reality platform. As his cartoon torso floats above homes flooded by Hurricane Maria, Zuckerberg helpfully makes subtext text: the dream of telepresence is to be there without taking on the risk that being there entails. This dream insists that technology will let (some of) us have it both ways: embodiment without proximity, knowledge without danger, pleasure without risk, and power without exposure. And it has been remarkably resilient, used to redefine everything from the nature of work, to the boundaries of warfare, to the contours of intimacy during a plague.

At its core, telepresence extends the reach of our bodies. The term itself is loosely defined, and can encompass a wide range of technologies with varying degrees of immersion. Used broadly, telepresence could describe something as familiar as a video call: a system for real-time communication that engages and expands the reach of our senses (in this case, seeing and hearing). In more precise application, it might refer to more-or-less sophisticated robots, like TelepresenceRobot.com’s speaker/camera unit on wheels, that allows users to move around and interact from a distant location. At its most robust, telepresence invokes complex systems for remotely manipulating and controlling environments, from the minute (surgical robots) to the far-reaching (military drones). For all their variation though, one constant remains: there is always, somewhere, a person in control.1

The paradox of remote presence at once constructs and blurs boundaries: between near and far, us and them, valued and expendable, human body and machine. Every promise of telepresence is a narrative of rupture and suture, a simultaneous making-more-than and less-than human. These technologies strike a bargain, imperfectly extending some of our senses while flattening the rest, connecting us to distant places and people while fracturing our bodies from their sensations, their labor, and the situated networks that physically sustain them. They ask, “what is the bare minimum we need to feel human?” And generally answer with, “whatever you need to do your job.”

And as they move ever closer to seamless embodiment (“It feels like we’re really here”), they promise, finally, to obscure their own presence. “Do you want to teleport somewhere else?” asks Zuckerberg, and then, in an instant, he leaves the devastated streets of Puerto Rico. When it feels like we’re really there, it’s easy to ignore the connections facilitating our “natural” experience: the systems that mediate our communication, the workers who build and maintain them, the ecosystems and laborers who supply the raw materials. We simply teleport away, as easily as we dropped in.

But whose interests and ideologies are concealed, and whose risk and labor is swept from view? Can a century of shifting dreams of telepresence tell us why this myth so stubbornly persists? Can they help us understand power, responsibility, and the ways that race and gender intersect with labor and technology? And can we learn from the dreams of the past and begin to imagine richer and more equitable forms of connection and care?

Videophone in Metropolis (1927).

Credit: klausnominomi

Almost a century ago, Fritz Lang’s 1927 landmark sci-fi film Metropolis vividly illustrated the conflicts and paradoxes, the ruptures and sutures, the simultaneous construction and blurring of boundaries that telepresence technologies would usher in.

In the first filmed portrayal of a videophone, the at-the-time fictional technology serves as connective tissue for the embodied, all-powerful computer system controlling a hyper-stratified dystopian city. From the comfort of his office on the 1000th floor, the city’s “master planner” consults statistics spewing from his “brain machine.” Concerned with the figures on the ticker tape that warn of an impending labor riot, he places a call to the foreman of the dirty, dangerous “hand machine” miles below. In the rigidly hierarchical world of Metropolis, the videophone terminals themselves manifest rank: above, there is a video display and no camera; below, a camera and no display. Through this asymmetrical technology, the city’s technocratic ruler physically extends both his senses and his will, surveilling and controlling the workers, while his body remains unseen and safely cocooned from the dangers below.

When Lang made Metropolis in Weimar-era Germany, the country was still reeling from the devastation of World War I. He and his audiences would have been acutely attuned to the body’s fragility in proximity to industrialized machinery. Against this backdrop, the videophone collapses and reinforces the vast distance between the city’s master and its vulnerable workers. Lang highlights their vulnerability in an indelible dream sequence that brings the trenches of war to the factory floor, where workers’ bodies fuel the ravenous, demon-faced machine powering the orderly city above.

Marvin Minsky in Omni, in a portrait accompanying his 1980 article on telepresence.

Credit: Dan McCoy

Less than a decade later, the videophone would make its nonfictional debut in the post offices of Nazi Germany2, just in time for the propaganda-laden 1936 Berlin Olympic Games.3 But the term ‘telepresence’ itself wasn’t coined until 1980, when computer scientist and AI pioneer Marvin Minsky published an article by that name.4 Minsky describes “new kinds of versatile, remote‑controlled mechanical hands”—a literal implementation of Metropolis’s “hand machine.” But his vision for telepresence quickly moves beyond specific technologies to encompass a total restructuring of labor and space:

You don a comfortable jacket lined with sensors and muscle-like motors. Each motion of your arm, hand, and fingers is reproduced at another place by mobile, mechanical hands. Light, dexterous, and strong, these hands have their own sensors through which you see and feel what is happening. Using this instrument, you can “work” in another room, in another city, in another country, or on another planet… Your dangerous job becomes safe and pleasant.

Minsky concludes that “many young people today consider it demeaning to be bound to any single employer, occupation, or even culture.” In his quintessentially neoliberal vision, “telepresence offers a freer market for human skills, rendering each worker less vulnerable to the moods and fortunes of one employer”—a view still promoted by gig economy employers like Uber, who frame their workers’ “independence” as a feature, not a bug. As in Metropolis, telepresence technologies entangle worker with machine, labor with capital. But where Metropolis depicts stark differences between proletariat and capitalist, Minsky articulates the myth of a classless “digital utopia” where, in media theorists Richard Barbrook and An dy Cameron’s words, “everybody will be both hip and rich.”5

Barbrook and Cameron’s unfortunately still timely 1995 essay locates the deep inequities that the Silicon Valley investor and C-suite class ignore: “Their utopian vision of California depends on a willful blindness toward the other, much less positive features of life on the West Coast—racism, poverty, and environmental degradation,” even as their technologies are “reproducing some of the most atavistic features of American society, especially those derived from the bitter legacy of slavery.” And in the present day, “this utopian fantasy of the West Coast depends on its blindness toward—and dependence on—the social and racial polarization of the society from which it was born.”

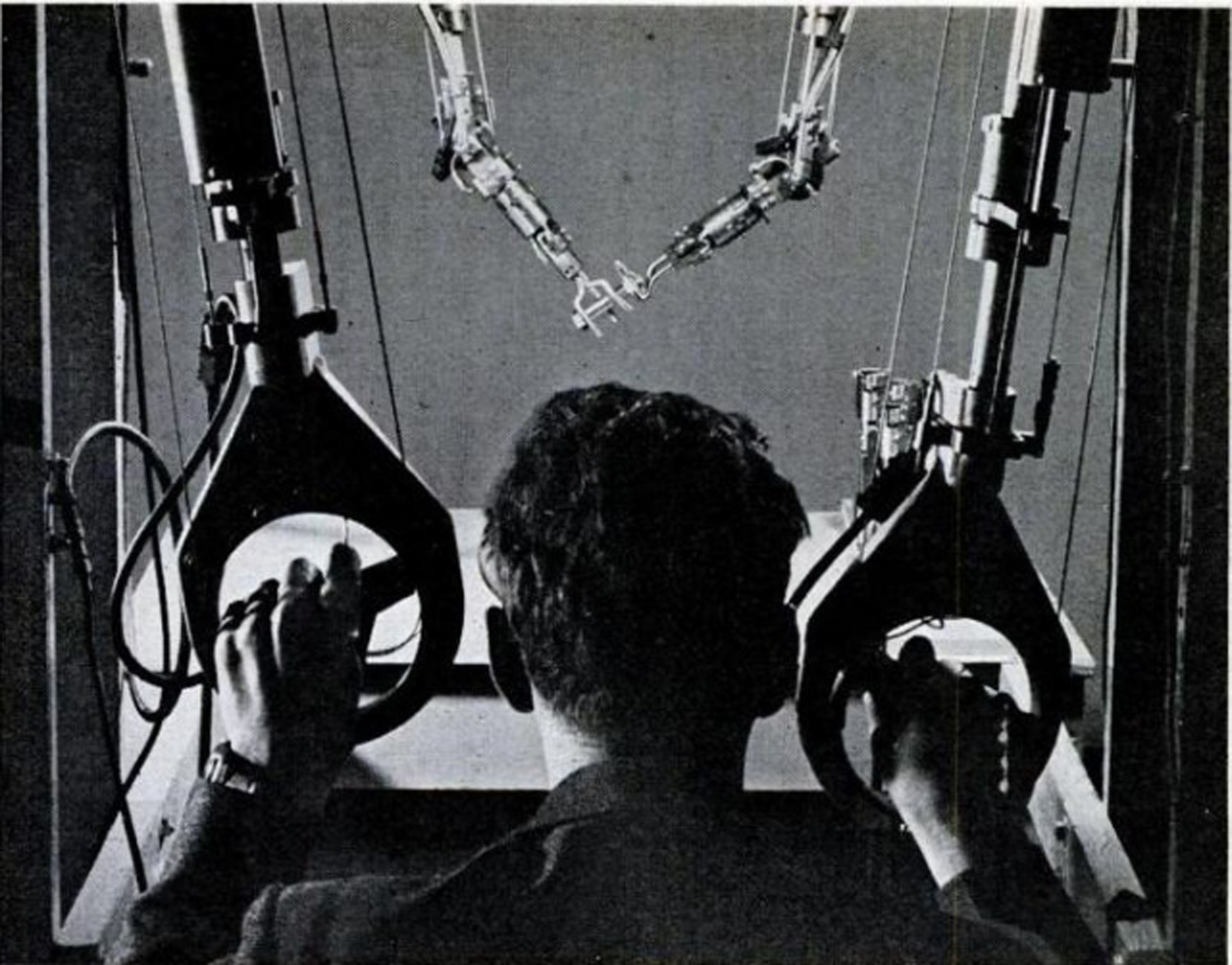

An operator using the GE Master-Slave Manipulator in Popular Science, June 1948.

Credit: Hobert Lushest, via Cybernetic Zoo

Minsky envisions a world where creatively fulfilled workers are free agents selling their professional services to the highest bidder. But this blinkered view fails to account for the “unfree and invisible labor… including indentured and enslaved labor as well as gendered domestic and service labor” that Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora assert has always been “the hidden source of support propping up” Minsky’s empowered contractors. In their book, Surrogate Humanity, Atanasoski and Vora argue that racial capitalism’s 6 desire and need for a “surrogate human” fuels a history extending from “the disappearance of native bodies necessary for the production of the fully human” to “the slave’s body as standing in for the master,” and into the current “disavowal of gendered and racialized labor supporting outsourcing, crowdsourcing, and sharing economy platforms.”7

This desire for surrogacy rests on the belief that anybody’s body can be easily separated from their home, their labor, and even their humanity. Simone Browne sees this belief enacted on an intimate scale, writing that the moment when a person is marked as black is “the moment of fracture of the body from its humanness.”8 Kathryn Yusoff sees a similar violent logic at work on a global and environmental scale, describing the European invasion of the Americas as a “rupture of bodies, flesh, and worlds” that marked the beginning of the Anthropocene: “an epochal redescription of geography as Global-World-Space.” For the native inhabitants of this redescribed world, colonization is “a process of alienation from geography, self, and the possibility of relation.”9

The ruptures of colonialism and enslavement lie just below Minksy’s bland assurance that “teleoperation will do away with hazardous and unpleasant tasks…In a remote‑controlled mining operation, there are no people to be hurt.” And the inequities of postcolonial globalization cast a shadow over his rosy promise that “a laborer in Botswana or India could market his or her abilities in Japan or Antarctica.” Minsky proposes a new, technologically-mediated form of rupture as a way to heal the sins of the past, but his aggressively ahistorical view neglects critical questions: Who currently does those hazardous and unpleasant tasks? Will Botswanan diamond miners enter a global labor market with the same bargaining power as a technology consultant in San Jose? For people whose skin color meant they were only recently deemed human, is the promise that “no people” will be hurt, in fact, reassuring?

From Minsky to Zuckerberg, telepresence is a dream of fracture without alienation, extraction without entanglement, and colonization without the colonized. Subtext is, once again, made text: mechanical arms built for handling radioactive materials (“Your dangerous job becomes safe and pleasant”) were named the Master-Slave Manipulator, a name that became—and, appallingly, remains—a generic term for mechanical arms like the one Minsky poses with.

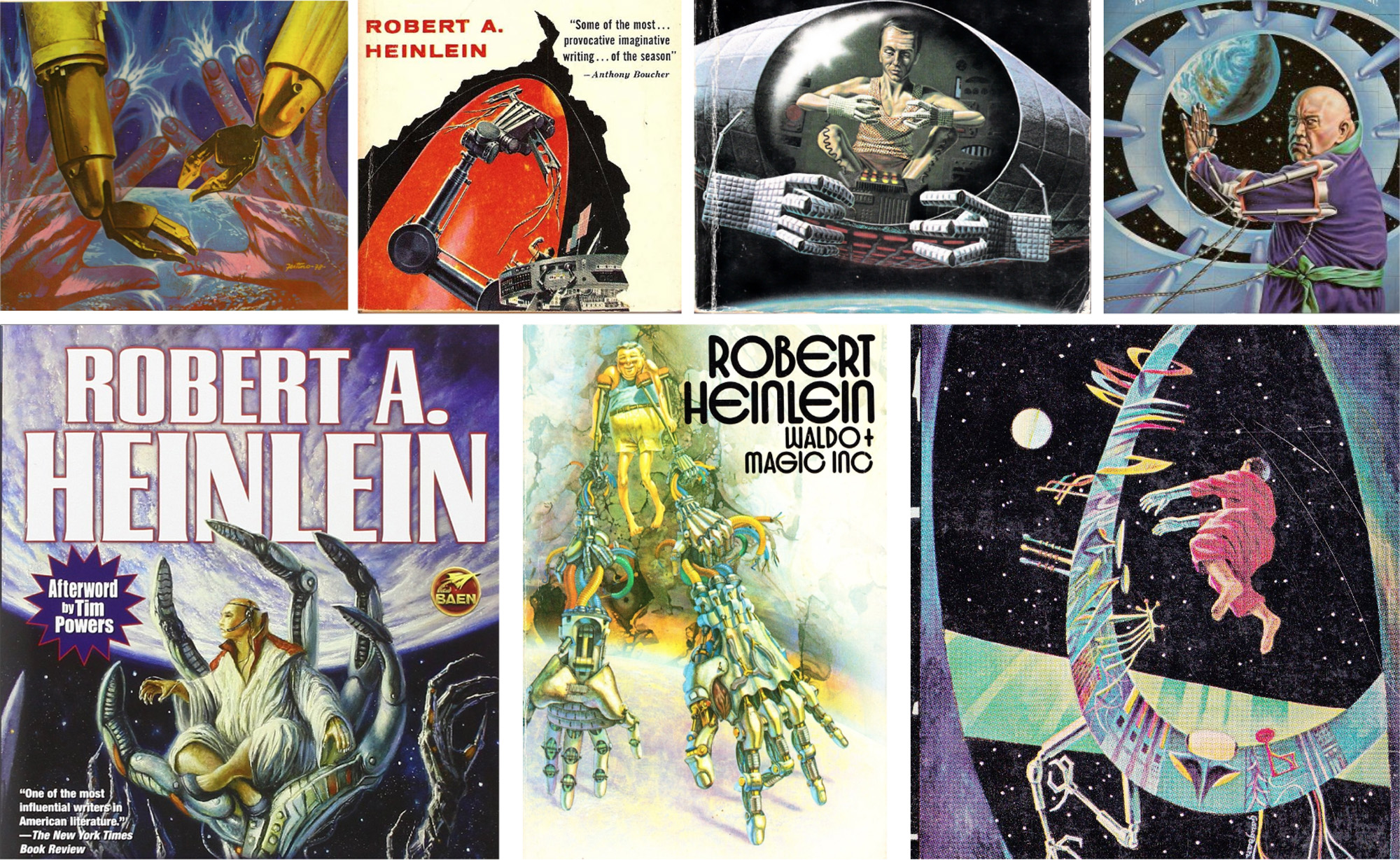

Cover illustration details from different editions of Robert Heinlein’s 1942 short story Waldo.

Cover illustration details from different editions of Robert Heinlein’s 1942 short story Waldo.

Early iterations of these “Master-Slave Manipulators” were nicknamed “waldoes,” 10 in homage to sci-fi writer Robert Heinlein’s 1942 short story Waldo, which was incredibly influential; in Minsky’s 1980 article, “Telepresence”, he explicitly credits Heinlein’s decades-old story as the inspiration for his vision of a technology-enabled “remote‑controlled economy.”

Heinlein and Minsky each describe their speculative technologies in imaginative detail. But where Minsky focuses on potential economic benefits and personal freedoms, Heinlein envisions the intimate power dynamics of such a system. Readers are introduced to the titular “waldoes”—a linked series of remote controlled robotic hands—in an overtly sexualized scene of dominance and submission. In this passage, the system’s space-dwelling inventor takes control of mechanical gloves worn by an earth-bound machine operator millions of miles away:

[Alec] Jenkins [the machine operator] thrust his arms into the Waldoes [the mechanical gloves] and waited. Waldo [the inventor] put his arms into the primary pair before him; all three pairs, including the secondary pair mounted before the machine, came to life. Jenkins bit his lip, as if he found unpleasant the sensation of having his fingers manipulated by the gauntlets he wore…

“Feel it, my dear Alec,” Waldo advised. “Gently, gently—the sensitive touch”…

“Rhythm, Alec, rhythm. No jerkiness, no unnecessary movement. Try to get in time with me.”11

Heinlein describes in detail the sweat dripping from the machine operator’s forehead as his hands are forcibly manipulated from afar. Exhausted, finally, Alec removes his hands from the metal gloves. Waldo is furious: still in control of the gloves, he uses one of them to violently grasp the other man’s wrist, threatens him with termination, and concludes to Alec’s supervisor, “Same time tomorrow, McNye. Progress is satisfactory. In time we’ll turn this madhouse of yours into a modern plant.”

In this extraordinary scene, coercion and desire intertwine with technology, power, and progress. Again, boundaries are at once reinforced and blurred: two men, separated by vast distances in space and socioeconomic status merge into a single flesh-and-metal assemblage to share a brief, fraught, and just-barely consensual “sensitive touch” in the name of industrial efficiency. In Heinlein’s depiction, even when the tech is flawless, the embodiment is anything but seamless. Despite the relentlessly optimistic terms that Minsky and his intellectual offspring use to describe telepresence, its original portrayal is deeply ambivalent.

This ambivalence is highlighted through several decades worth of spectacular cover illustrations; with echoes of Metropolis’ omniscient city planner, artists portray an ominous, all-seeing figure floating high above the earth, cybernetically linked with grasping, mechanical hands. As viewers, are we meant to imagine ourselves as the powerful, misanthropic Waldo? Or are we looking up at him from Alec’s point of view, waiting for his robotic hands to grasp ours?

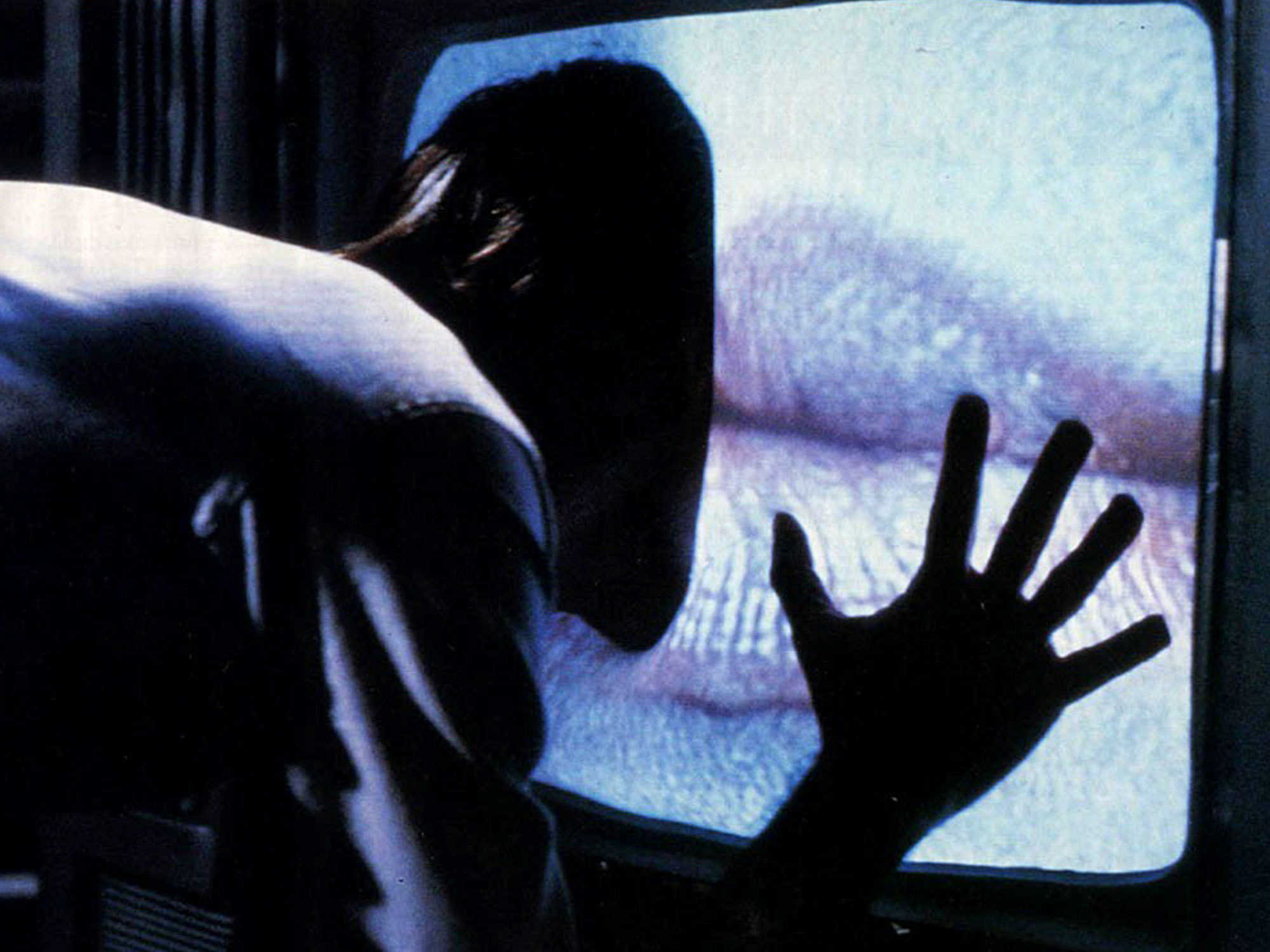

Still from Videodrome (1983) of a fleshy, pleasure-giving and -receiving television.

Still from Videodrome (1983) of a fleshy, pleasure-giving and -receiving television.

“Can telepresence be a true substitute for the real thing?” Minsky wonders. “Will we be able to couple our artificial devices naturally and comfortably to work together with the sensory mechanisms of human organisms?” (emphasis is mine). In his 1983 film, Videodrome, David Cronenberg answers this question with an uncomfortable vision of unnaturally fleshy machines that desire us, control us, and irreversibly transform us into something neither wholly human nor machine—in the film’s parlance, “the new flesh.”

A kind of treatise on the pleasures and perils of Heinlein’s mechanically mediated “sensitive touch,” Videodrome delves deep into the power dynamics and potential consequences of a world where the boundaries between ourselves and our machines—and the opaque corporate powers controlling them—have completely dissolved. Half a century after Metropolis, Lang’s room-size computers and cavernous factory floors have been replaced by small, personal devices inside our homes; protagonist Max’s adult cable station bills itself as “the one you take to bed with you.”

But over the course of the film, we’re introduced to a fictional technology even more intimate than VHS porn. In the world of Videodrome, telepresence manifests as a tumor or a virus, living and replicating itself within our bodies at the cellular level. The effects of this literally embodied technology are drastic and uncertain. In the film, Kelly Pendergrast notes, “bodily integrity is constantly being violated… with results as exhilarating as they are scary.”

With echoes of Heinlein’s robotic hands, Cronenberg’s haptically sensitive television sets extend their users’ sense of touch. Pendergrast points out that in this AIDS-era film, “bodies are foregrounded as sites of pleasure and vulnerability (and pleasurable vulnerability).”12 In Cronenberg’s telling, opening oneself to intimacy and repressed desires renders us susceptible to manipulation and physical danger. Videodrome’s protagonist ultimately loses his grip on reality, his sense of self, and control over his actions. Cable executive Max begins the film in control of television programming, and ends it as a human VCR, manipulated by shadowy figures with obscure motivations. As one antagonist says, “Open up for me, Max. I’ve got something I want to play for you.”

In this telling, the machine-mediated ruptures of being there without being there have serious consequences: both the terrifying fracture of objective reality and the sensuous potential of cybernetic transcendence. In the words of the film’s media prophet, a Marshall McLuhan stand-in, “you’ll have to learn to live in a very strange new world.”

- Founder and producer of Afrotectopia, Ari Melenciano, enjoying the event.

Stills from a 2020 promotional video for Amazon’s “Ring Always Home Cam” show the flying drone and the Ring app it transmits live video feed to. Credit: Amazon

Over the decade after Videodrome’s release, the strange new world Cronenberg envisioned became an anxious reality. As the military-funded ARPANET metastasized into the World Wide Web, theorists and practitioners alike would grapple with the spatial and sensorial contours of such a dramatically altered landscape. In the 1996 book, City of Bits, architect William J. Mitchell depicts these changes with cyberpunk bombast typical of the era:

Soon we will be able casually to create holes in space wherever and whenever we want them… Once, places were bounded by walls and horizons. Days were defined by sunrises and sunsets. But we video cyborgs see things differently. The Net has become a worldwide, time-zone-spanning optic nerve with electronic eyeballs at its endpoints.13

Today, we may not identify as video cyborgs, but we’re certainly surrounded by electronic eyeballs. In October 2020, eight months into a global pandemic, Amazon announced their internet-connected Ring Always Home Cam with the intensely absurd, laugh-to-keep-from-crying tagline “The future is now… enjoy being always home.” Unintentional irony aside, the company’s domestic surveillance drone continues a decades-long trend towards ubiquitous, distributed computing and the surveilling gaze it enables. From Metropolis on, “electronic eyeballs” have been inextricable from telepresence technologies; and like those technologies, the risks and rewards associated with surveillance are distributed along racialized lines.14 Chris Gilliard calls attention to the distinction between “expensive, voluntary, and sleek” “luxury surveillance”—of which the $249 Always Home Cam is a prime example—and the “involuntary, overt, clunky, imposed surveillance” of, say, a court-mandated ankle monitor. Gilliard traces how these stratified dynamics leak from bodies and homes to “create different spatial experiences for users on opposite ends of the tool—and for different races and classes at the receiving end of the surveilling gaze,” ultimately reshaping “the social life of entire neighborhoods, communities, and cities.” 15

The luxury/imposed surveillance dynamic Gilliard locates extends nationally and internationally, as well. A direct line, ideological as much as technical, connects the “luxury” Always Home Cam to the armed Predator drones inflicted by the US upon Afghanistan, across the Middle East, and, later, along its own borders and on its own citizens.16 An armed drone may be the most undiluted expression of telepresence, and the military, unlike Amazon, is happy to say the quiet part out loud. In A Theory of the Drone, Grégoire Chamayou quotes an Air Force officer who explains that “the real advantage of unmanned aerial systems is that they allow you to project power without projecting vulnerability… Self-preservation by means of drones involves putting vulnerable bodies out of reach.” 17

Metropolis’ prescient vision is evoked once again, as remote operators, tucked safely away in places like Creech, Nevada or Clovis, New Mexico, consult their “brain machine”—dozens of monitors displaying maps and statistics—about the dangerous, faraway places where their “hand machine” does its dirty work. Like Gilliard, Chamayou notes the spatial dimensions of these risk-displacing technologies when “the body that is vulnerable is removed from the hostile environment… space is divided into two: a hostile area and a safe one.”

Right now, we all have a vested interest in removing our vulnerable bodies from hostile environments. And the pandemic—or, more accurately, the inadequate and deeply cruel response to it by both government and corporate entities—has exposed a stark logic linking Zoom calls and food delivery to drone warfare. When physical presence is dangerous, some (richer, whiter) people get to use technology to avoid that risk at the expense of (poorer,browner) people who have been deemed expendable.

I’m thankful for the privilege of working remotely, and grateful for tools that help me stay connected with family and friends—and, despite concerning track records of censorship, harassment, and racialized exclusion, there’s nothing inherently harmful or racist about telepresence technologies. But until much larger and deeper fractures are addressed, the dream of being there without being there will continue to mask an abdication of responsibility. And as our technologies of telepresence move closer to the stated goal of seamlessness—as they become more embodied—the traces of ideology we still can discern keep getting fainter.

Kimoyo bead technology in Black Panther. Via Sci-Fi Interfaces/Christopher Noessel.

Kimoyo bead technology in Black Panther. Via Sci-Fi Interfaces/Christopher Noessel.

Could there ever be a form of telepresence that facilitates connection and communication without reinforcing long-standing ruptures and inequities along lines of class, race, gender, and disability? One possibility lies in a different understanding of embodiment in the technological context.

Feminist scholars of science and technology studies might argue that an embodied technology that obscures its broader effects represents a profound misunderstanding of embodiment, or even what it means to have a body. Lisa Blackman describes bodies not as stable things, but as “processes which extend into and are immersed in worlds,” and proposes that, “rather than talk of bodies, we might instead talk of brain–body–world entanglements.”18These entanglements are present in Donna Haraway’s foundational concept of situated knowledges: ways of learning and knowing that are “about communities, not about isolated individuals.” Such knowledge must be learned as a “knowing self”: “partial in all its guises, never finished, whole, simply there and original; it is always constructed and stitched together imperfectly, and therefore able to join with another, to see together without claiming to be another.”19

Black Panther’s kimoyo beads are one potential expression of an entangled, situated telepresence. Artist Brian Stelfreeze—who, with writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, built the comic book world of Wakanda from which the 2018 film was adapted—drew on his experiences and history as a Black American to inform their design:

Where I’m from, the people are known as Gullah people. They’re some of the first freed slaves that lived on their own, without being attached to the rest of the U.S. They kind of developed their own culture, so they do things a little bit different. Growing up in that area and going to the rest of the world, I noticed things were just slightly different… So I thought, “what if that happened over thousands of years? How could technology evolve?”

The beads are rooted in a specific place and culture, and attuned to their physical and social environment. As Stelfreeze explains, the Wakandans’ technology “mimics nature because it comes from nature.” Further, these technologies are site-specific; they draw their power from the vibranium in Wakanda’s ground and “when you leave, it’s like taking out the battery.” Stelfreeze designed the kimoyo beads to be worn as a familiar bracelet (“a lot of black folk wear stuff like that”) in explicit contrast to what he sees as the “industrial way,” which produces inflexible devices that force users to adapt to them, rather than devices adapting to the user. The bracelets are modular—with individual beads for communication, piloting, projection, healing, etc—and grow and change along with their wearers. Finally, they are attuned to varied, and embodied, modes of communication; “because they’re around your wrist, [they] pay attention to your hand” and so recognize spoken as well as signed language.

The rich and nuanced telepresence of kimoyo beads remains, for now, out of reach, in a speculative world with radically different priorities and incentives than our own. Technology, by itself, won’t level the skyscrapers in Lang’s Metropolis, won’t heal the ruptures accumulated over centuries of colonization and enslavement that neoliberal techno-utopian visions elide, won’t reconcile the pains and pleasures of cybernetic entanglements, and certainly won’t satiate the hunger for power and control that surveillance—luxury or otherwise—feeds. But, at its core, a truly embodied telepresence might need only answer one question, articulated by Donna Haraway with characteristic elegance and clarity: “With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”20

Footnotes:

- Critically, these systems are not automated—but they may be a step towards automation, and increasingly include forms of automated surveillance and decision making.

- Special Correspondent, “Public Television in Germany,” Times (March 3, 1936), 15.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “The Nazi Olympics Berlin 1936,” Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- Marvin Minsky, “Telepresence,” Omni (June 1980), 44-52.

- Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “Californian Ideology,” Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias, ed. Peter Ludlow (MIT Press, 2001), 363-387. Originally published in 1995).

- A concept proposed by Cedric Robinson in his 1983 book Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, described succinctly by Nancy Leong as “the process of deriving social and economic value from the racial identity of another person.” Nancy Leong, “Racial capitalism,” Harvard Law Review (June 2013).

- Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora, Surrogate Humanity: Race, Robots, and the Politics of Technological Futures (Duke University Press, 2019), 6-9.

- Simone Browne, Dark Matters: on the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015), 91.

- Kathryn Yusoff, “White Utopia/Black Inferno: Life on a Geologic Spike,” e-flux architecture (2019).

- Reuben Hoggett, “1942 – Waldo, Waldoes and Master Exoskeletons,” Cybernetic Zoo.

- Robert Heinlein (as Anson McDonald), “Waldo,” Astounding Science-Fiction (August 1942).

- Kelly Pendergrast, “Network of Blood,” Real Life (July 29, 2019).

- William J. Mitchell, City of Bits: Space, Place, and the Infobahn (MIT Press, 1995), 34.

- See Simone Browne, Ruha Benjamin, Mimi Onuoha, and Sarah T. Hamid, among many others, for fuller discussions of the links between race, technology, and surveillance, from its roots in enslavement to its current carceral applications.

- Chris Gilliard, “Caught in the Spotlight,” Urban Omnibus (January 9, 2020).

- See Brian Bennett, “Police employ Predator drone spy planes on home front,” Los Angeles Times (December 10, 2011). Declan McCullagh, “DHS built domestic surveillance tech into Predator drones,” CNET (March 2, 2013). Rebecca Heilweil, “Members of Congress want to know more about law enforcement’s surveillance of protesters,” Vox (June 10, 2020).

- Grégoire Chamayou, A Theory of the Drone, trans. Janet Lloyd (The New Press, 2015), 11, 22-23.

- Lisa Blackman, Immaterial Bodies: Affect, Embodiment, Mediation (SAGE Publications, 2012), 1.

- Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies (1988), 575-599.

- Xavier Harding, “‘Black Panther’ Has The Coolest Tech In The Marvel Universe,” Popular Science, May 10, 2016

Livia Foldes (she/her) is a New York-based multimedia artist, designer, and educator working in the latent space between activism, storytelling, and technology.