Issue 8: Disembodiment

Every Voice Heard: Imagining Feminist Voice Technologies

As our devices increasingly occupy our personal spaces, smart technology is poised to impact how we socialize, how we relate to one another, and how we view our bodies. How are these technologies shaping our bodies and our relationships to one another? And how can we reimagine our smart technologies to better reflect a feminist articulation of embodiment?

During a pandemic, our technologies take on new meaning. With a disease that forces us to be distant, we’ve become even more reliant on technology to mediate our relationships, how we take care of others and ourselves.

Doctor’s appointments occur over the internet or by telephone and people have to say goodbye via FaceTime to their loved ones languishing near death in hospitals. While we grapple with a daily reality that demands we think about our bodies and the bodies of those around us, we’ve also been coerced into new ways of isolation.

The global pandemic has raised important questions not considered until now: How do our technologies connect us to or detach us from our embodied, lived experience? Do the devices we interact with every day – Alexa, Siri, Garmin, Fitbit – support noticing what is happening in our bodies? Do they help us notice what is happening in our conversations and our relationships? Do they remind us to spend more time in nature? Do they alert us when our communities are in need and connect us with mutual aid networks? And finally, are these various technologies truly assistive or accessible? Or do they merely invent new methods of control?

Many technologies further entrench – rather than question– already existing systems of power. For the past few years, our collective, tendernet, has written about and led workshops on how feminist principles can help guide new, critical conversations about technology and power. How can we reimagine our technologies so that they reflect our own values, rather than a tech company’s values? In our work, we’ve specifically explored how an intersectional feminist lens might help us reimagine the design of voice technologies.

Technology and social power

Historically, technology has created or shaped the conditions for violence and oppression. On the most basic level, voice technologies reinforce gender norms. : The default “voice” of our technologies is typically female. From early telephone operators connecting people through wired cables and switchboards, to secretaries and personal assistants, to voice assistants like Alexa and Siri. Often these disembodied, helpful female voices contribute to gendered fantasies of women occupying subservient caregiver or administrative roles. Moreover, in a 2017 survey of popular voice assistants, journalists found that when confronted with abusive, violent, or sexually explicit language, most voice assistants responded by evading the comment (“Let’s change the topic”) or defusing the situation with humor (“I’d blush if I could”). Such interactions suggest that Siri or Alexa, the two prominent agents of evasion, were not designed to acknowledge and confront our biases, or navigate difficult conversation, or even educate or inspire us.

In many ways, this isn’t a surprising development. Voice technologies have been conceived as tools to connect companies with their customers, so values like education, consent, respect, and equity are not considered as important as convenience, speed, and return on investment (ROI), which, as values, are more culturally ingrained. These priorities are reflected in Amazon’s telling documentation for its Alexa voice assistant: users are referred to as “customers.” A company’s failure to engineer alternative, more equitable values into social technologies is a symptom of bigger structural problems in the industry.

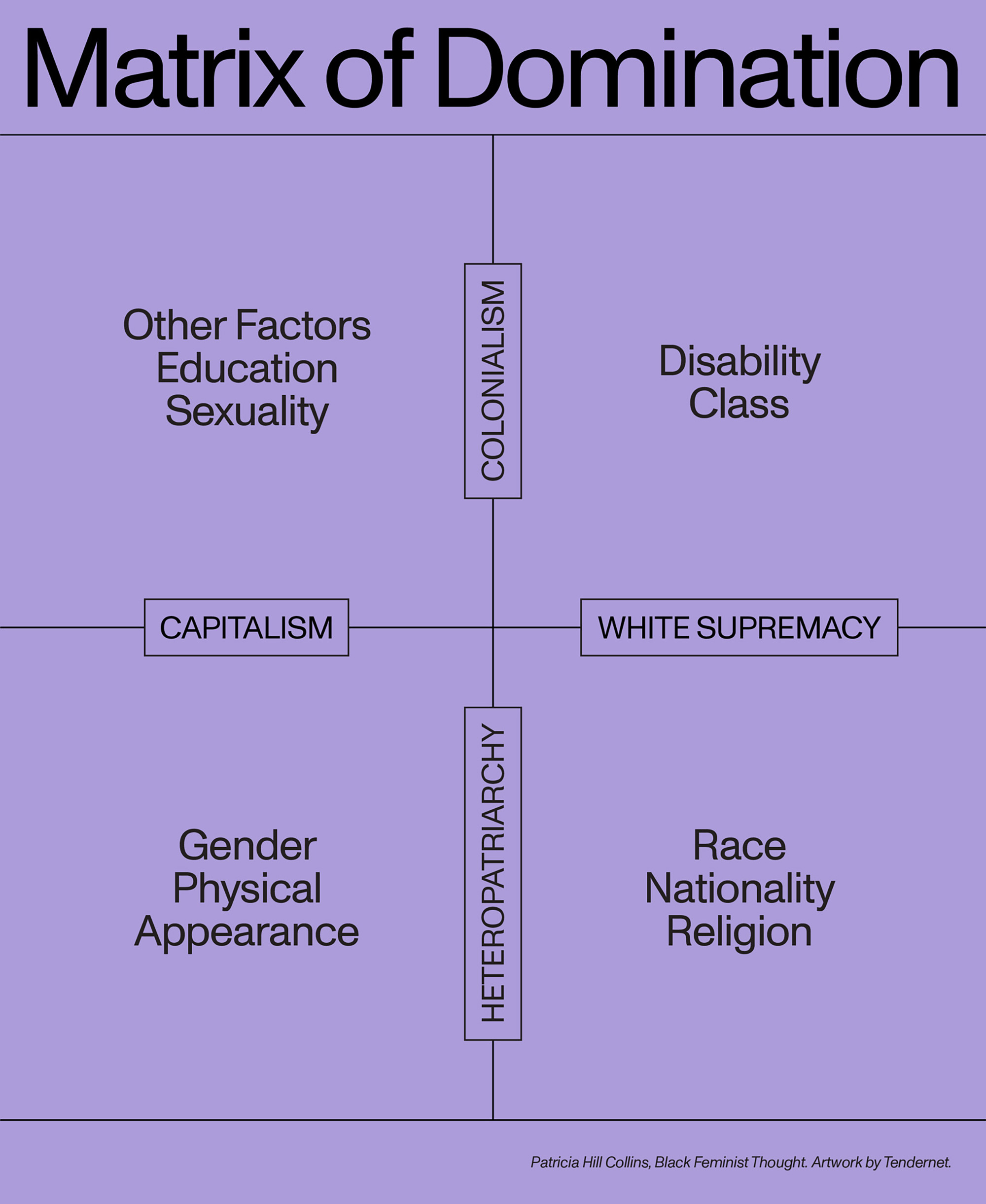

These technologies re-articulate oppression, according to what is described as the matrix of domination,”1 a sociological paradigm developed by Patricia Hill Collins to describe the intersection of power structures and forms of identity. According to the matrix of domination, people experience oppression not only through categories of identity: race, gender, disability, or class, but through the intersection of larger, structural systems, such as white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. For instance, a voice assistant’s inability to parse non-American English accents might mean that, say, a Latinx woman might experience forms of oppression when she uses it, including racism, colonialism, and sexism.

Designs by Katrina Peterson

Designs by Katrina Peterson

An intersectional feminist analysis of technology allows us to think about how multiple oppressions and regimes of power shape the way people access and use technology. It also allows us to think about how we can intervene in, disrupt, or replace these patterns by imagining feminist protocols that take their place.

Prompt: How does the matrix of domination show up in other technologies?

What is a feminist protocol?

Feminism is a set of practices that we enact with one another. Feminist protocols, as defined by Michelle Murphy, are “standardizable and transmissible components of feminist practices”2 that change how things are done. These protocols take on new meaning as they move across different spaces or disciplines. Feminist protocols can take the form of small-scale, site-specific interventions. For instance, changing our speech patterns to replace abelist language is an example of a feminist protocol that can be repeated and habituated in our everyday conversations. Another example of a feminist protocol might be a voice assistant that says “stop!” or initiates a difficult conversation when confronted with harassing language, much like existing forms of feminist anti- harassment interventions.

Prompt: What are examples of feminist protocols you enact every day?

Technology can be a site for feminist intervention. One example of this in practice is the Feminist Principles of the Internet, which offers a gender and sexual rights lens to technology. Drafted in 2014, the principles were developed by a global, intersectional group of feminist and human rights activists that acknowledge the internet itself can be a matrix of domination. The feminist internet movement has led to a number of interventions, including discussions about how the technical infrastructure of the internet itself – policies, standards, architecture – could be revised to reflect feminist principles.3 For instance, the group treats surveillance as a core feminist issue and works to hold governments and companies accountable for the dangers of non-consensual data collection.

But creating sites for interrogating technology and imagining alternatives also requires new ways of thinking about and executing principles of design. As such, feminist methodologies have emerged as revisions to traditional models for prototyping and building technology. For instance, Sasha Costanza-Chock’s book Design Justice introduces innovative ways of thinking about design through the lens of justice and equity4. And the book, Data Feminism, co-authored by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein, explores how data scientists and technologists might integrate feminist frameworks into their work.5 Scholars in the emerging fields of feminist HCI, post-colonial HCI, and gender HCI, aim to offer new tools for developing more liberatory technologies. These approaches view technology through the lens of justice and social power, calling on designers and data scientists to develop more community-centered, radically inclusive, and participatory methods for building tech.

Hackathons and workshops centered on intersectional feminist values and activism are two examples of these participatory methods being put into practice. Hackathons, specifically, can be powerful sites for education and learning, but they are also radical and alternative models for participatory design. Such spaces should include not only people with lived experience and expertise, but especially those communities and people who are most affected by the technology.

Globally, activists, designers, artists, and technologists are creating more participatory, inclusive sites for intervention: A feminist hackathon to redesign the breast pump as a way to “iterate feminist utopias,”6 a series of workshops exploring feminist data creation for AI development, a toolkit for envisioning transfeminist technologies from Coding Rights in Brazil, workshops to prototype a Feminist Alexa in the UK, and the FemTechNet network, which engages in practice-based scholarship and activism. We consider our own series of workshops, Imagining Feminist Interfaces, both a site for empowering participants to speculate alternatives and an approach to design that takes an explicitly activist stance. These interventions may feel small when considering how deeply the matrix of domination is ingrained in our technologies. However, these interventions themselves act as feminist protocols. They transform how we think about technology as they inhabit new spaces and contexts, fueling social change.

Feminism and interaction design

Our collective, tendernet, is a group of artists, technologists, researchers, designers, educators, and activists examining technology through an intersectional feminist framework. As part of our work, we run speculative design workshops in which we imagine technologies that embody some of the central commitments of feminism. In our first round of workshops held in 2019, Imagining Feminist Interfaces, we imagined and protoyped feminist alternatives in voice technologies.

We decided to focus on interaction design in our socially-engaged practice because intervention is at the heart of both feminism and design. Feminism is a “natural ally to interaction design,” writes Jill P. Dimond, because it is a tradition that “strives to address various forms of oppression in a specifically activist stance.”7 Feminist interventions can give us insights into design and help us better understand how to shift norms and behaviors.

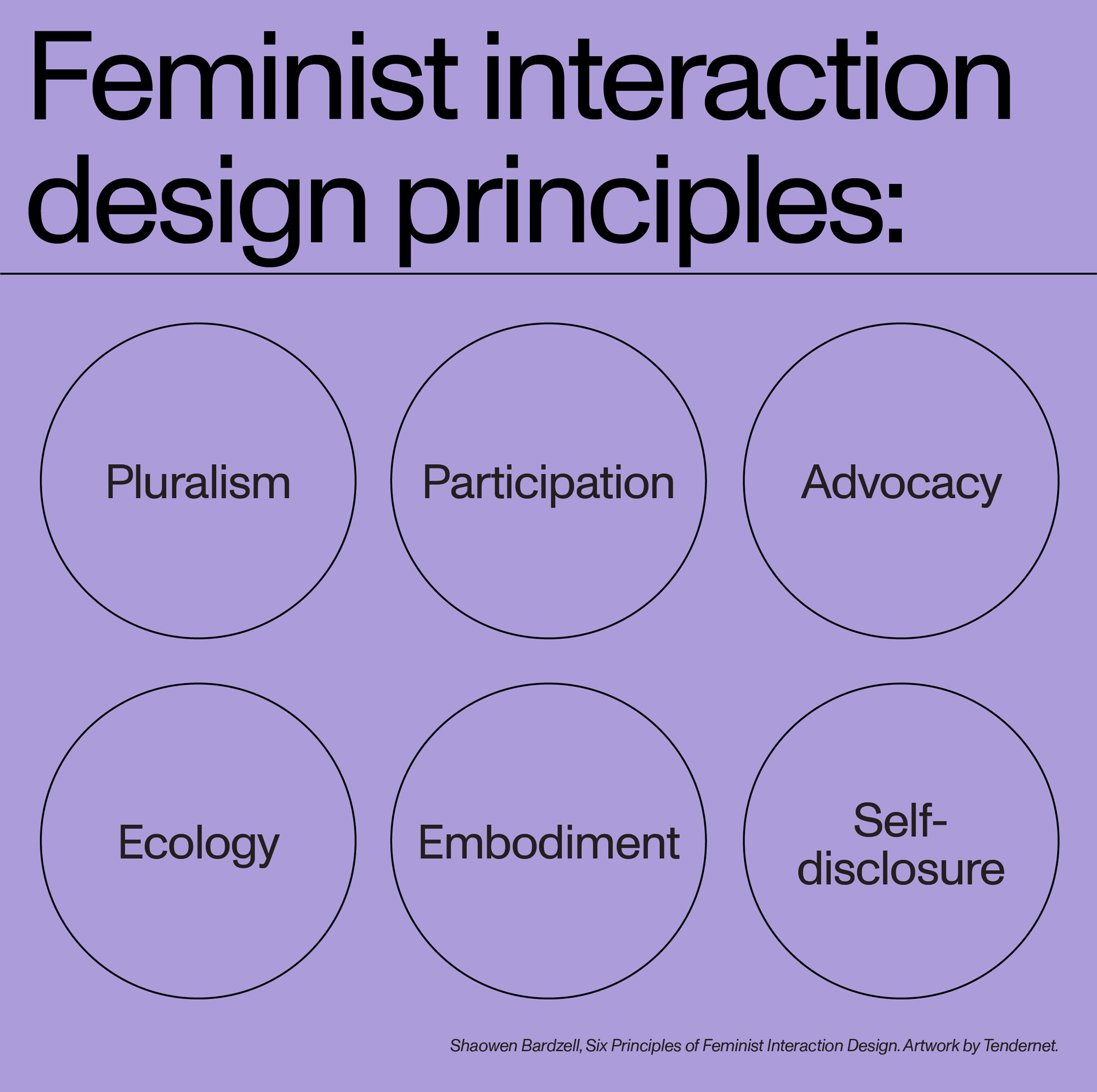

Before we can imagine what feminist technologies might look like, we need to develop a shared language for thinking about how an intersectional feminism can inform design choices and methods. In our workshops, we always begin by asking participants what feminism means to them and discussing what values they care about. As a starting point for further exploration, scholar Shaowen Bardzell’s outlines six key principles of feminist interaction design8:

Designs by Katrina Peterson

Designs by Katrina Peterson

- Pluralism: The interface represents a diverse set of viewpoints (heterogeneity).

- Participation: Users are actively engaged in every stage of the design process (a participatory approach).

- Advocacy: People can question the values built into the design as they work towards developing interfaces that embody justice.

- Ecology: There is an acknowledgement that design exists within and impacts larger social structures / ecosystems.

- Embodiment: Users are recognized and treated as material, embodied people (rather than disembodied users).

- Self-disclosure: The interface makes the assumptions and choices that were made in the design process visible to the end user.

Prompt: Think about one of the last technologies you interacted with. Pick one of these principles and make a list of the ways the technology does or doesn’t fulfill the principle.

Participation and pluralism are key components of feminist interaction design. Participatory design, or co-design, is a design approach that actively includes the people who use the tech in the design process. This means that the communities that are most impacted by the technology should actively shape the values that are embedded into its design.

This idea runs counter to today’s dominant approach to software design, where technologies are designed for a wide range of people and communities without meaningful community input. And even when participatory design methods are used in research settings, they tend to be extractive, drawing insights from participants in design research workshops without creating opportunities for people to actively shape or refuse the end product.

There are many examples of successful co-designed technologies. For example, , a fan fiction archive called “Archive of Our Own” was designed and developed entirely by women in 2007 using the platform, serving over 750,000 users. Their design choices “were informed by existing values and norms around issues such as accessibility, inclusivity, and identity,”9 resulting in an archive that was created by the people who actually used it. And the features – which included language diversity, user-controlled tagging and search, and anonymity – reflected their value system.

Prompt: Think about an app or device you love using. Now imagine what it would look like if its most active and knowledgeable users could co-design it.

Imagining a feminist voice technology

In keeping with these principles, we ran our workshops in a range of different spaces and contexts, including a feminist zine fair in Manhattan, a hackerspace in Brooklyn, NY, a contemporary art museum in Toronto, Canada, and a university design conference in Providence, RI. In each case, the goal was to foster an inclusive space in which anyone could participate, regardless of particular expertise or experience.

While the format of the workshops varied, depending on the audience and context, each workshop operated from three key assumptions:

- Design exists within and shapes larger social structures and ecosystems, and these systems determine the way different communities access and use technology.

- A feminist approach to voice design isn’t just about making our voice assistants less sexist – it’s about using interaction design to shift power.

- Communities that are most impacted by technology should be able to actively define and shape the values embedded in its design.

In developing our workshops, we reflected on the gatekeeping that exists in Silicon Valley and tech culture more broadly. There are lines drawn between the non-technical and technical, the non-coders and the coders, the non-designers and the designers, suggesting that only people with a technical background can offer meaningful insights into a technology. We tried as much as possible to erase those artificial boundaries in order to acknowledge and elevate the diverse forms of knowledge and experience that participants brought with them to the workshop.

Many participants had no coding experience, but they had all used voice-based technology before. Many had never thought about designing a voice interaction, but they were all part of communities that used different vernaculars and languages. Most didn’t even own a voice assistant, but they knew the frustration of being misunderstood, neglected, or rendered invisible by a technology. These experiences are all relevant and important kinds of knowledge that are frequently overlooked by software developers.

Prompt: Think of a time a technology didn’t work for you. What broke? Why?

Depending on the makeup of the workshop’s audience, we curated the session to meet the needs of the participants. In a group with no technical coding experience, we facilitated a discussion about our personal relationships to voice technologies and imagined how they could be improved. At a design conference, we ran a speculative design sprint in which participants asked “how might we?” questions to brainstorm what alternative voice assistants could do. In other workshops we led a speculative activity with “found” artifacts: decontextualized transcripts of chatbot conversations that made us think about how our culture and values shape the technologies we build. In a group with more coding experience, we taught participants how to code their first Alexa voice skill and practiced prototyping their ideas.

During the course of these workshops, participants asked meaningful questions and imagined alternative use cases for voice technology. Questions raised included:

- How do we work within user experience design – which aims to build appealing interfaces – while trying to challenge what people feel is most easy and appealing? How can we make interactions feel less comfortable? Challenge people’s assumptions?

- How do we tackle the notion of a “default voice”? What does it mean to “choose” a voice? How might we remove gender (or any identity) from the voice while acknowledging difference?

- How might we build a voice that recognizes non-white, non-American, non-western voices, phrases, and names? Could we use AI to recognize a wider range of accents, or even understand two languages (bilingual) at once?

- What would it look like for a small, intimate speech community to define its own rules for voice interactions?

- How do we advocate for feminist ideas when working with companies who don’t share that vision? How might we design a voice that is not owned or facilitated by a company? How might we develop a crowdsourced, open source voice interface?

- Can a voice assistant be used as a community tool to resist police violence or surveillance? Alert communities? Could it intervene in a crisis or does it become complicit/weaponized in a police state?

- Could we create worker subversive Alexas? How might we create a voice interface that draws attention to the human labor involved in making it? Could a voice interface help connect tech workers or gig workers to organize?

These questions help get us closer to the critical conversations that we will need to have to architect different, more equitable futures. But feminist interventions also require taking what we learn from such conversations and putting them into action. We don’t just critique the technology in our workshops, we actually redesign it. We follow the feminist protocol of participation by facilitating inclusive design exercises that ask participants to reimagine these technologies through everything from paper sketches to software prototypes.

Taking these questions as inspiration, workshop participants work in small groups to design a voice assistant that reflects the values held by themselves and their communities. The outcomes of these exercises are broad, reflecting the diversity of participants in each workshop and the distinct context of each event. Here are a few of the interventions and technologies that participants have designed:

- A voice skill that helps reduce the pay gap by coaching users in negotiation skills and promoting wage transparency;

- A voice assistant that checks in on elders, making sure they’re taking care of themselves and reminding them to address issues before they become larger problems;

- A posthuman voice assistant that enables people to speak to non-human entities and ecological systems, encouraging them to get in touch with their natural surroundings;

- A therapist voice assistant that initiates deep, difficult conversations and notifies family members or friends if something serious happens.

Though these designs only exist as speculative ideas, they’re an opportunity for us to reflect on and change the relationship we have to our existing technologies. By designing these technologies from an activist stance, we’re creating our own set of feminist protocols. We hope that design interventions like ours empower people to speak out when technologies harm or sideline them, advocate for more inclusive design processes, lead discussions in their own communities, and architect a feminist, liberatory future.

What comes next?

We believe that anyone – not just people building tech – are able to actively shape the values embedded into a technology’s design. We imagine a future where our technologies are designed in a way that is more participatory and reflect a multiplicity of experiences. We want a future in which we can hack and control our technologies to have them work on a small scale–for small language groups, small communities, and for small, intimate conversations. We want a future in which we have the power to say NO and have the choice to refuse some technologies when they don’t reflect our values.

As we continue to imagine new feminist protocols for interacting with our most intimate technologies, we can expand the boundaries of possibilities. And, by working with different communities and exploring these questions together, we can imagine and architect better, more pluralistic futures.

Footnotes

- Hill Collins, Patricia. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Rev. 10th anniversary ed. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Murphy, Michelle. Seizing the Means of Reproduction: Entanglements of Feminism, Health, and Technoscience. Experimental Futures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

- Guerra, J. and M. Knodel. “Feminism and Protocols,” July 8, 2019. https://tools.ietf.org/id/draft-guerra-feminism-01.html#rfc.section.4.

- Costanza-Chock, Sasha. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Information Policy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020.

- D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. Data Feminism. Strong Ideas Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2020.

- Hope, Alexis, Catherine D’Ignazio, Josephine Hoy, Rebecca Michelson, Jennifer Roberts, Kate Krontiris, and Ethan Zuckerman. “Hackathons as Participatory Design: Iterating Feminist Utopias.” In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. CHI ’19. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300291.

- Dimond, Jill Patrice. “Feminist HCI for Real: Designing Technology in Support of a Social Movement,” August 20, 2012. https://smartech.gatech.edu/handle/1853/45778.

- Bardzell, Shaowen. “Feminist HCI: Taking Stock and Outlining an Agenda for Design.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1301–1310. CHI ’10. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753521.

- Fiesler, Casey, Shannon Morrison, and Amy S. Bruckman. “An Archive of Their Own: A Case Study of Feminist HCI and Values in Design.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2574–2585. CHI ’16. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858409.

Additional References

- Chivukula, Sai Shruthi. “Feminisms through Design: A Practical Guide to Implement and Extend Feminism: Position.” Interactions 27, no. 6 (November 2, 2020): 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3427338.

- Rentschler, Carrie. “Feminist Protocols: Auditing Urban Infrastructures and Reporting Gender Violence in the City.” Mediapolis (blog), February 27, 2020. https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2020/02/feminist-protocols-auditing-urban-infrastructures-and-reporting-gender-violence-in-the-city/.

- Sezgin, Emre, Yungui Huang, Ujjwal Ramtekkar, and Simon Lin. “Readiness for Voice Assistants to Support Healthcare Delivery during a Health Crisis and Pandemic.” Npj Digital Medicine 3, no. 1 (September 16, 2020): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00332-0.

Zoe Bachman is an artist and educator whose interdisciplinary practice involves research, pedagogy, and the creative uses of emerging technology. She is a graduate of NYU-ITP, member of The Illuminator, and co-founder of the feminist technology collective tendernet. Zoe currently works as the Sr. Curriculum Manager at Codecademy, where she focuses on finding new ways to make technical education more accessible and engaging.

Becca Ricks is a technologist, researcher, and artist interrogating the design of AI and computational systems. She works at Mozilla Foundation as a researcher, exploring how principles like accountability, transparency, and participation are operationalized. Formerly, Becca was a 2017-2018 Ford-Mozilla Open Web Fellow hosted at Human Rights Watch. She is a founding member of tendernet, an intersectional feminist collective exploring critical and speculative design practices around AI. Becca holds a master’s degree from NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (NYU-ITP).