Kinship: Colonial Organisms

Diving into the world of colonial organisms, one is hit with a myriad of scientific jargon straightaway: zooid, bryozoans, siphonophores, polymorphism and the list goes on and on! But what are they?

Colonial organisms (i.e. colonial animals, colonial-forming animals, superorganisms) are animals that are made up of many individual organisms, of the same species, that are attached together to form a colony. The individual organisms are called zooids, and they are not able to live on their own, outside of the colony structure. The rely each other for survival.

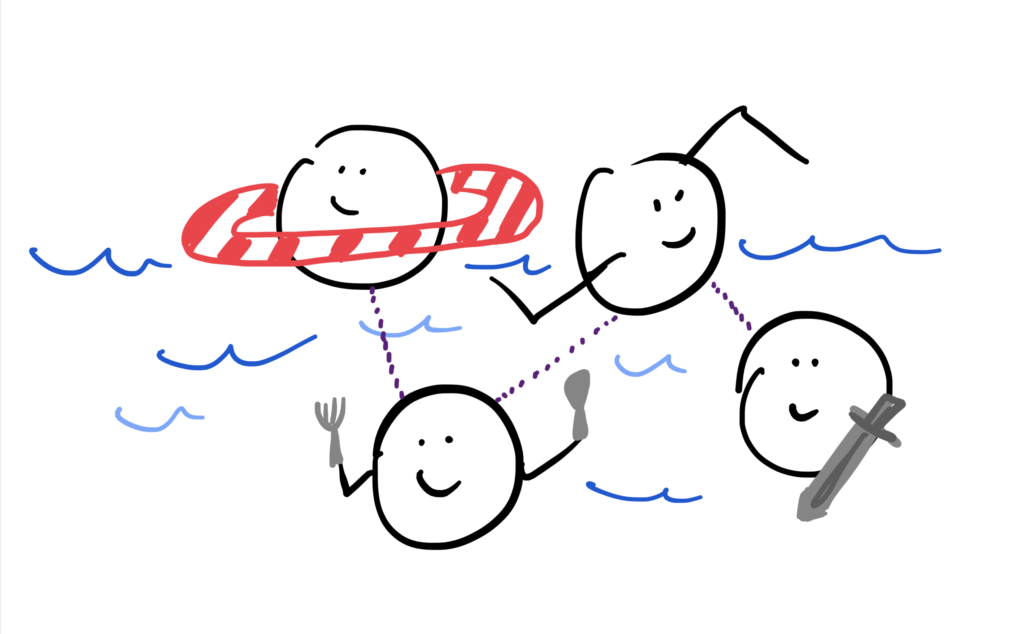

There are some species where all of the zooids within the organism are identical clones of each other. There are other species where each zooids fulfills a different need for the organism as a whole: each category of zooid works together to make sure that the organism is protected, fed, is able to navigate, etc. Siphonophores, one type of colonial organism, have zooids that have evolved to catch food, other zooids work to protect the organism, and others still handle navigation and swimming so that the organism can move around. This idea of a species having different types or forms is referred to as polymorphism.

I found this paradigm particularly linked to the excerpts from adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy. Several times brown brings up biomimicry, which is the “imitation of the models, systems, and elements of nature for the purpose of solving complex human problems.” She even uses the example of ant societies as one of the principles of emergent strategy where individuals act collectively to survive. While ants don’t fit the definition that of colonial organisms, in that they aren’t attached, they are certainly organisms that live in a colony and act for mutual benefit of their society.

As mentioned above, some colonial organism zooids produce identical clones of themselves. Corals, bryozoans and other species however create offspring which are genetically similar but not identical. These offspring are recognized by the parent colony as “kin cells” as Lara Beckmann notes in The Fascinating Lives of Colonial Animals. “Only cells with sufficient genetic similarity are accepted – others are not welcomed and will be rejected.” By evolving to combine with other colonies, instead of just reproducing identical zooids, these colonial organism species increase their genetic diversity. This may be why these colonies “grow faster, are more resilient against environmental threats, and that competition with less closely related neighbours is reduced”.

As I continue to explore colonial organisms within the context of kinship, I wonder if kinship that we see in human relationships is another early form of biomimicry, or is it another example of an evolutionary habit that the human species has adopted.