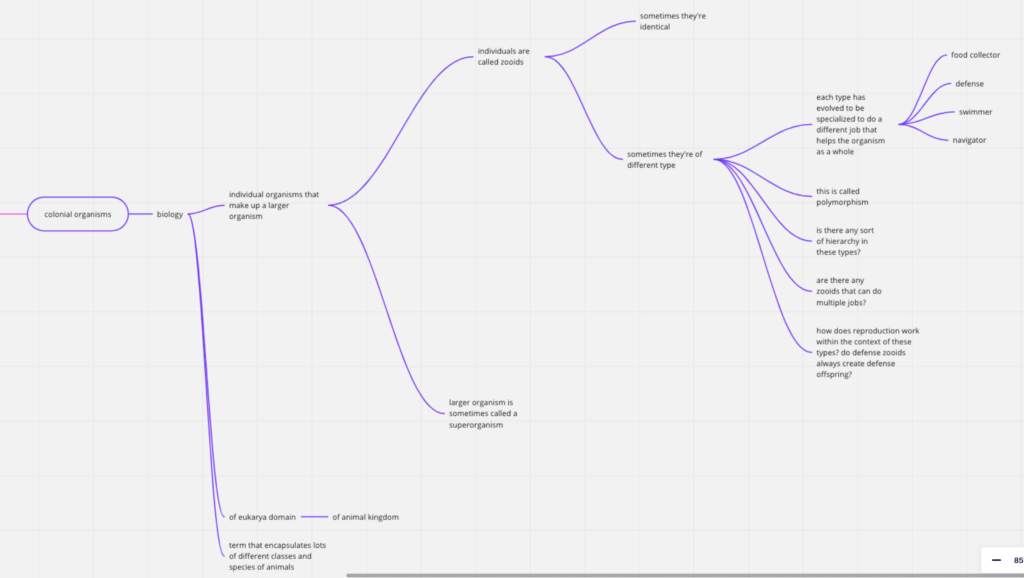

Colonial Organisms: Systems Maps

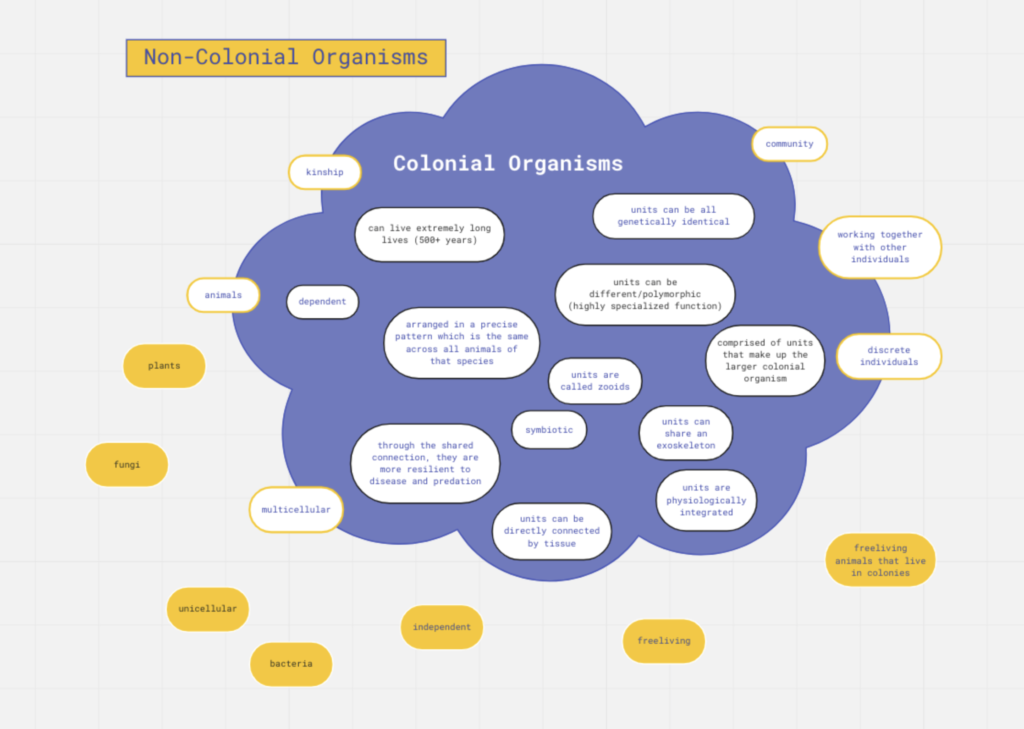

I was finding it difficult to create a concept map of colonial organisms, because I think that my understanding of the definition of a colonial organism is still quite tenuous. I decided to start out with a boundary map to see if I could solidify my understanding a bit more.

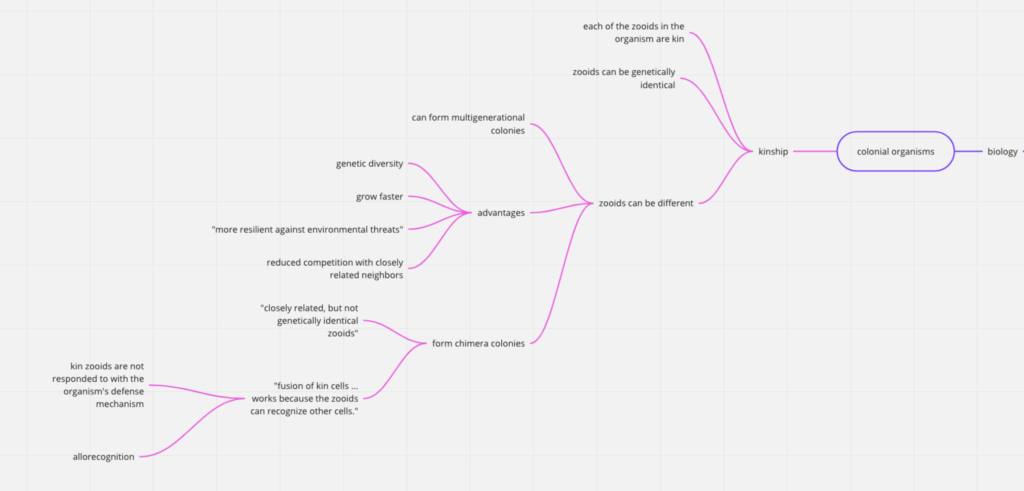

As I continued working, I realized that though coming up with a definition of a colonial organism seems like it should be straight forward, but it wasn’t. Perhaps the complexity I was running into is because human understanding of all organisms exist within the implied context biology taxonomy. I have learned that colonial organisms are animals, but I kept wondering “what is an animal?”. The individual zooids that make up colonial organisms seems like pretty simplistic animals, so how are they different from moss, or bacteria?

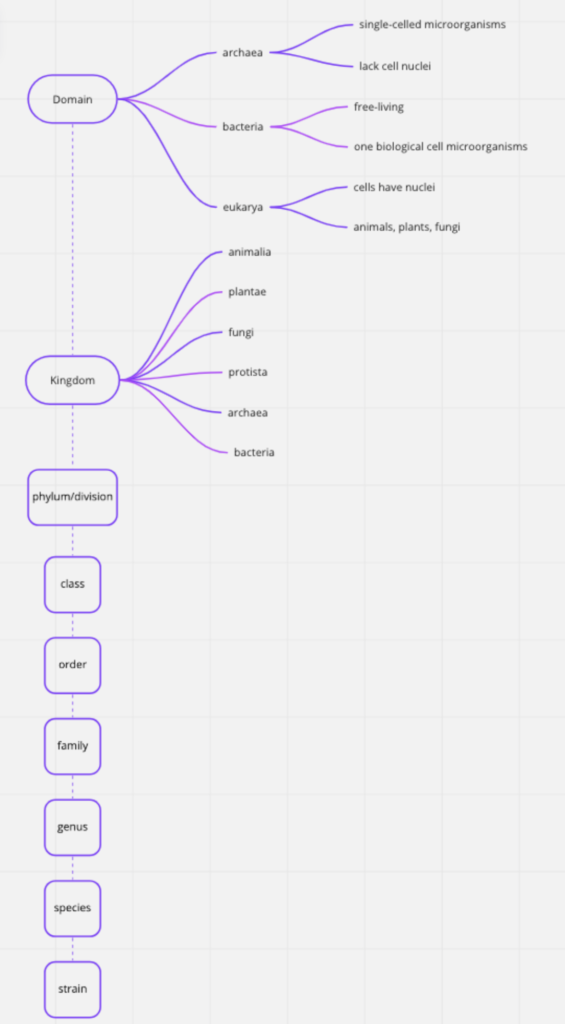

I started to build out a biology taxonomy digram, but quickly learned that once you get to the phylum classifications, the tree expands a lot. I’m not sure that documenting all of the known phylum classifications will help me understand colonial organisms any better, so I stopped at the kingdom level, and discovered that animals are in fact separate from bacteria. This was a helpful discovery because one thing I wondered in my early research was why humans weren’t classified as colonial organisms, since we have bacteria in our body, could they be zooids? Apparently the answer is no, bacteria in our bodies are not classified as zooids, and therefore we are not colonial organisms.

Links to miro boards:

- boundary map: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVPVNaV40=/

- biology taxonomy: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVPVSZHYs=/

- concept map: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVPWOgdo0=/