Brachen, Rewilding, and Mappamundi

I did research in several different veins this week, further exploring gardens and borders. There are a couple of directions that look promising that I want to dig deeper into.

I read a little bit about the gender roles in maintaining cottage gardens, finding that it has gone back and forth between a feminine and a masculine duty over the centuries. I also learned that in the early 1800’s in England, there was an effort to give gardens to people in the working class. It was thought that “the male labourer possessing and possessed by his garden was to be made moral through useful bodily toil” (Sayer 45). Simplistic and paternalistic.

I then turned my attention to the Brachen in Berlin and several rewilding efforts. It is here that I want to spend the bulk of my research time moving forward, as I feel I have just scratched the surface and I am captivated. The Brachen in Berlin were abandoned spaces, caught between the eastern and the western sides of Germany during the Cold War. These spaces, at one time industralized, were allowed to fall into disrepair, and plants reclaimed the space. Then, once the wall fell, developers started re-taking these spaces. I ready about how these Brachen, for so many, represented hope and possibility when they were industrial voids — far more than anything they became.

I want to learn more about the power of plants to take over man-made things. I want to find examples of other places where this has been documented, and I want to research what happened in the first couple months of the pandemic when the US/Europe/Asia was at its most shut-down. I would like to capture the duality of the fragility and resilience of the plant species that inhabit our past and present.

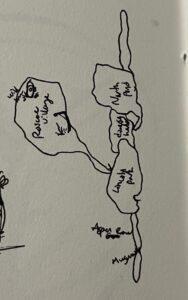

Tactically, I am still interested in the mappamundi, and I think I want to make one from the perspective of the plants (likely local to Chicago) and try to use that as a media to record them/tell their story, or something along those lines. I found the mappamundi intriguing in that they “by exaggerating the spread of time depicted within their borders, the mappamundi also demonstrate that maps in general need not be seen as reflecting only spatial realities… they may also consist of historical aggregations or cumulative inventories of events that occur in space.” (Woodward 519). The mappamundi captured geography, yes, but also history, religious stories, and itineraries. They cant necessarily be used to locate latitude and longitude of towns, but they could probably tell you the order that you would come across those towns as you moved up a given river. There were also precise legends inscribed in them, and they captured illustrations of different animals and humans.

I think this is something I’d like to explore from the perspective of plants in Chicago. Maybe there is a good way to capture some of the history of the landscape and plant species as they have changed over time. Maybe there are ways to also capture the plants that are still here – weeds, cultivated, I’m not sure. I’d like to talk to someone at the Morton Arboretum or someplace similar for my interview to try to get some of that information. Also, just as the people who were trying to protect the Brachen in Berlin did not put them on a map for fear of calling attention to them, I like that a mappamundi would not give you terribly accurate locales of any of the plants included. Not that I’m all that worried, but it ties in with our reading about refusal, as well.