Topic 1 (Puppets): Form Analysis

Qiu Zhijie, Map of “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World” (2017),

94 1/2 × 283 1/2 in (240 × 720 cm)

- Why this form? What are its features (stylistic, experiential)

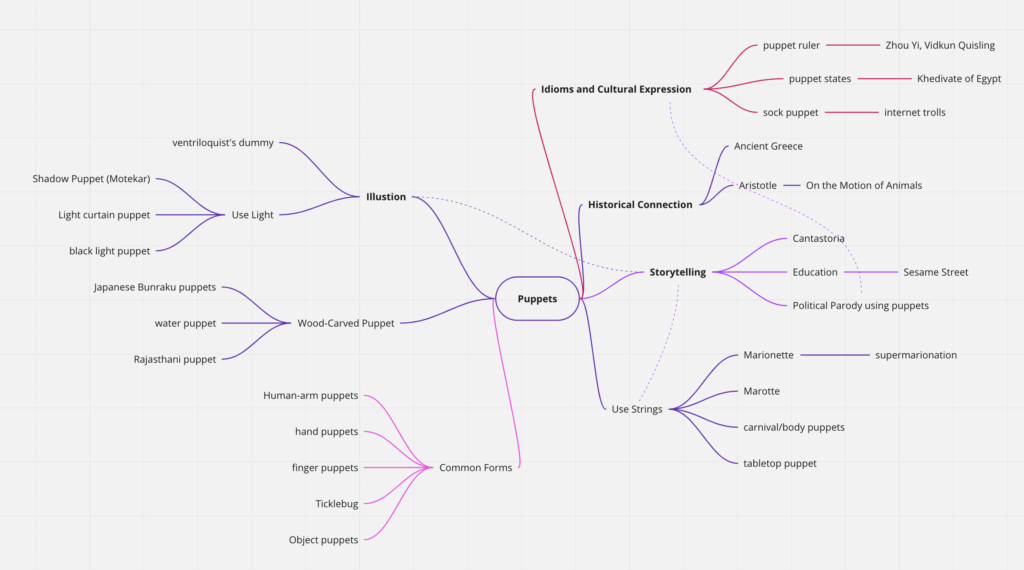

I first saw Qiu Zhijie’s work in the “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World” exhibition at Guggenheim in 2017, it was a gigantic wall-size, ceiling-tall 6 panels Ink on paper. It doesn’t really obey aesthetic rules, and it seems like an overwhelming amount of information trying to be delivered at first glance. Honestly, in a group show of 71 artists, it wasn’t the most eye-catching. In fact, I remember seeing a lot of people skipping this one and going on the other more visually pleasing works. However, if you get closer to the map, and try to read and understand it, you will soon be shocked by the cleverness of it. The artist has a strong understanding of art history, politics, and colonial history, and somehow combines all of that into a readable map of a non-existing world. While serious, it was also mixed with some sense of humor and subtle mockery.

- How is this form typically used, and what do you plan to subvert/imitate/utilize?

A map is typically used to deliver geographic information and ideally be as neutral as possible. For example, disputed territories should be labeled as disputed instead of being labeled as whatever country the map maker is in favor of. However, in Qiu Zhijie’s version of map making, maps become a place where concepts formed into geographic territories, and where the artist is able to share all the information he had digested. I plan to learn from Qiu, and utilize the concept of a map, yet subvert it by utilizing my ugly handwriting and sincere outsider drawing skills to create a map that aims to compile everything that is meaningful to me and related to puppets.

- What would change if you tried a different form? What critical lens does the form you’re applying emphasize?

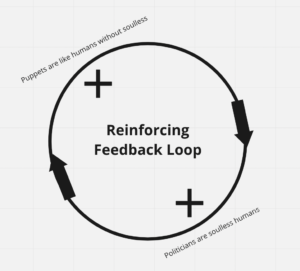

If I adopt a different form, I’ll narrow the topic a little bit more, which I understand can be desirable for a research project. By choosing to make a complicated map, I will be facing the risk of having things too vague, with no focus for the viewer. However, I find it to be an interesting challenge, as I’m often too afraid to go big in a project, so this can be a good exercise for me. A lot of emphases will be on how I construct the information. Instead of being neutral, what I learned from Qiu, as well as standup comedy, is to treat everyone equally bad. This means it’s okay to poke fun, just make sure all the stakeholders in the system are being equally offended.

- Is there a metaphor well-suited to your form (i.e. cooking with code)? Or, are there other metaphors you might employ?

I’m not sure how to answer this question, I guess Qiu Zhijie’s unique mapping technique is what I’m trying to employ and learn from.