Topic 2 Interviews

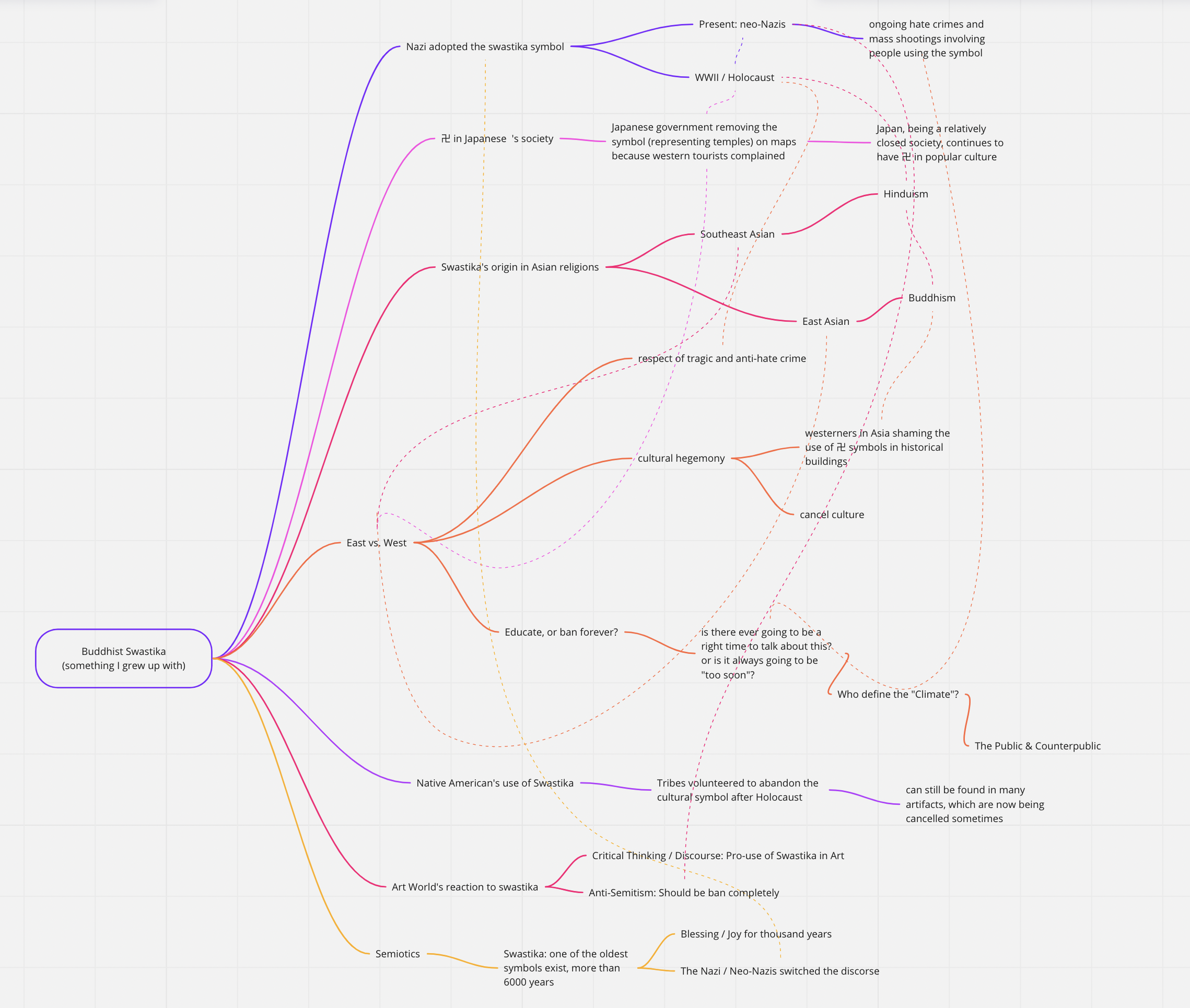

For the interview, I talked to two people in my life. One is my friend, Nic, a 31 years old American scholar. Another is my uncle, Wen-Pin, who’s a 62 years old Taiwanese guy, practice Taoist Buddhism his whole life and have never been to any western countries if not including Hawaii.

——

Are you familiar with the origin history of the Swastika symbol?

Nic: Of course. It was borrowed from ancient religions.

Wen-Pin: Yea. The Buddhist one is the opposite from the Nazi’s one, it’s different! But aside from Nazis, I believe the Crusades and maybe something else also used the symbol in war and invasions.

——

Do you know many of the Native American tribes also used the same Swastika symbol for thousand years, but voluntary dropped it after the Holocaust happened?

Nic: Interesting. I did not know.

Wen-Pin: No, but I’m not surprised.

——

Do you think Buddhist and other religions using similar symbols should also stop using the symbol to avoid confusion?

Nic: I don’t think so.

Wen-Pin: Of course not? Each country should mind their own business. I respect the suffering and the tragic of the Holocaust, but I don’t think the West should have a say on what we’ve been using for centuries.

——

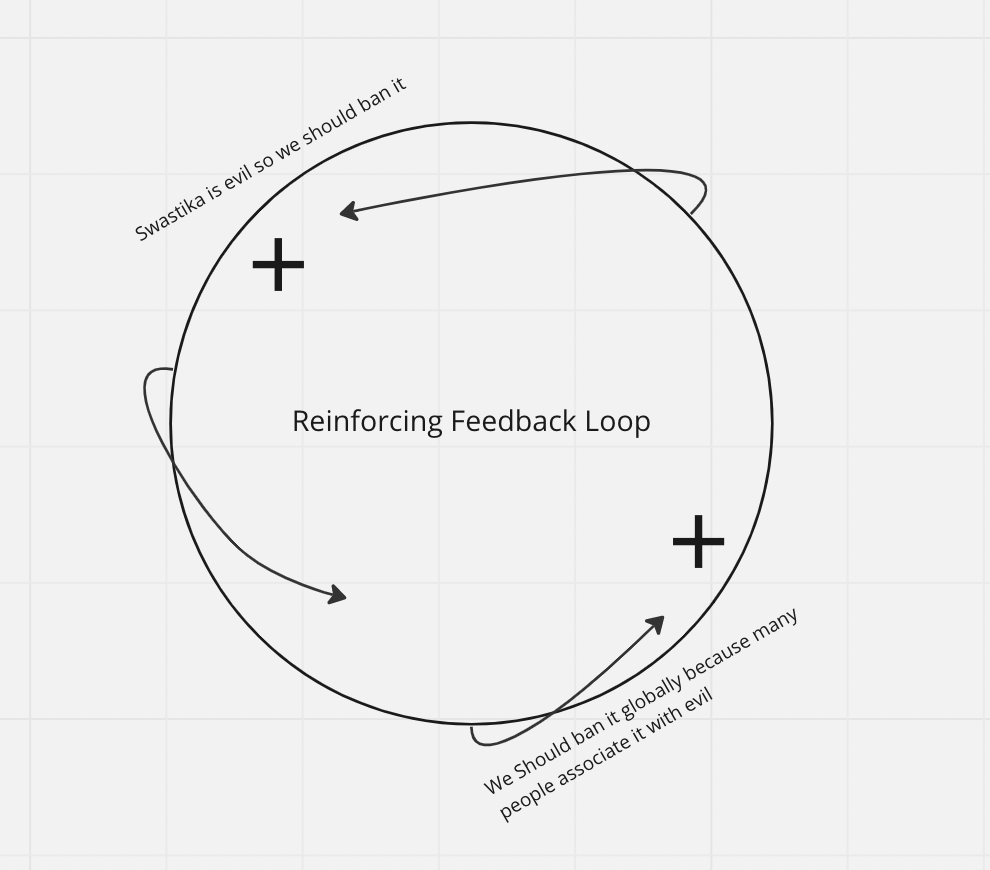

Do you think we should help reclaim the original meaning of the swastika?

Nic:…..okay….this is a tricky question. I don’t think it’s an appropriate topic at the moment. Things have been really sensitive and anti-semitism is still a very real issue in our society.

Wen-Pin: I think it would be nice if the West learn and educate the public about the history of the symbol. It is important to respect where everyone’s coming from. But also, this is not really my business, as long as nobody is coming to my home and banning the Buddhist swastika in my own family shrine.

——