Wyna Liu ’14 (MPS, ITP), Courtesy of the New York Times | Photo by Caleb Bryant Miller

Written by Alex Manges, Assistant Director of Alumni Relations

In the word game world, the New York Times’ Crossword Puzzle has long been considered the gold standard for both avid and amateur puzzlers alike. The Times published its first crossword puzzle in 1942, and by 2014, the game had become so popular that the publication launched an entire Games section, both online and in print, with the addition of the Mini Crossword. The Mini was followed shortly that same year by Spelling Bee, and in 2022, the Times acquired the viral word game Wordle that had so many of us hooked during the COVID-19 pandemic.

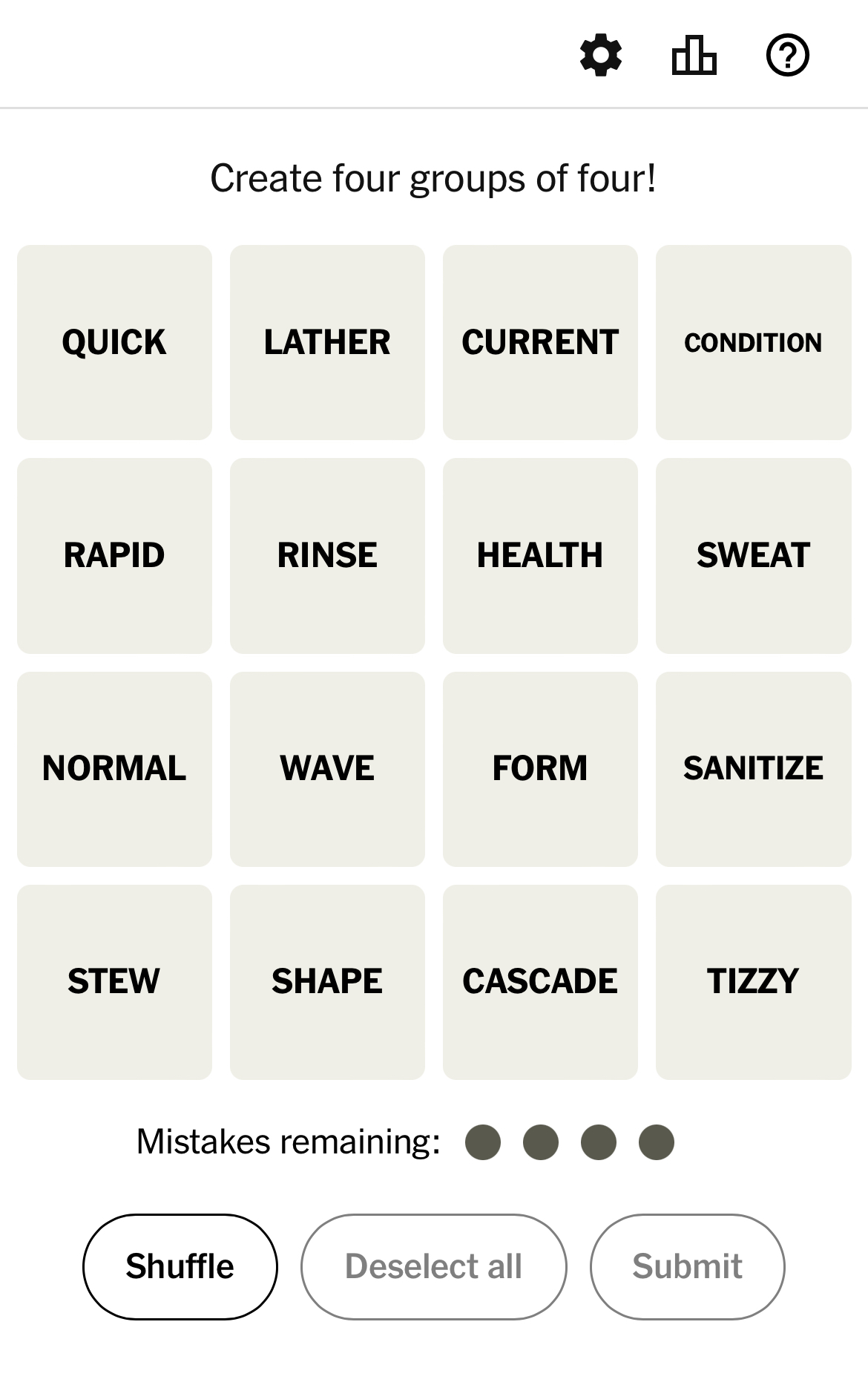

The most recent game added to the collection was Connections in 2023, which sparked a similar craze to its immediate predecessor. Connections is a word game in which the player must take 16 words and find the common thread between 4 groups of 4 words, ranging from the most straightforward to a real head-scratcher (think “Breakfast foods” to “Car companies minus a letter”).

Like Wordle, Connections gathered a near-immediate following and remains on the daily game roster for many English-speaking players a year and a half after its initial release. Players often publicly lament a losing day, taking to TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), or Instagram to gripe about the puzzle or call out the editor herself to explain a category.

“At this current time in my life, the tone and vibe of my day is completely determined by my feelings about that day’s New York Times Connections puzzle,” TikTokker Jake Cornell said in a video in January. In April, Ioana Burtea published An Open Letter to Wyna Liu, the New York Times’ Connections Editor. And in June, when the Times posted a celebratory video on the one-year anniversary of the release of Connections, one user commented, “So my mortal enemy has a name.”

That name is Wyna Liu ’14 (MPS, ITP), a graduate of the NYU Tisch’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP).

So, how does Wyna feel about the public attention on her work? She loves it.

“I think it’s amazing,” she says earnestly as we talk over lunch on a hot day in Soho. “I feel incredibly fortunate that something I love doing, that I work hard at and that I’m proud of, is something that people enjoy doing. I’m also happy they enjoy talking about it, and even seem to enjoy being mad at it!” she laughs. “I get it; I love being mad at stuff.”

“Do you like getting frustrated by puzzles?” I ask.

“I do!” she says. “I love that feeling of, like, grrrrrr when you’re working on getting something. If it’s too easy, it’s hard to feel like you’ve accomplished something.”

Some, myself included, may mistakenly believe that Wyna herself created the game. However, Connections was born out of a New York Times annual event called Game Jam, where NYT Games’ staff members explore new ideas for games and features for existing games. Only the best of the best games are greenlit, and when Connections was created and approved in 2023, they needed an editor to bring it to life. This is where Wyna, a Puzzle Editor at the Times since 2020, entered the picture.

“I had never had my own game,” Wyna says. “Joel (Fagliano) had the Mini, Sam (Ezersky) had Spelling Bee, and Tracy (Bennett) had Wordle. I was the only other editor, so they asked me if I wanted to do this game, and I said, ‘Okay! Sounds like fun!’”

Like her clues in Connections, Wyna herself is many things simultaneously. On top of being a puzzle editor and avid puzzler, she is also a jewelry designer and makes sculptural wearable art out of her home in Chinatown, Manhattan. She’s exploring making wax models for casting, taking neon-making classes, and raising her rescue dog, Polo.

A graduate of Oberlin College, she came to NYU Tisch’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP) in 2012. For those unfamiliar with the program, think of it as a playground for today’s most creatively inclined technical minds—or the most technically inclined creative minds! ITP’s mission is to explore the imaginative use of communications technologies, offering a 2-year MPS degree for working professionals who wish to expand their understanding of the relationship between art and technology.

So, what brought Wyna here in the first place?

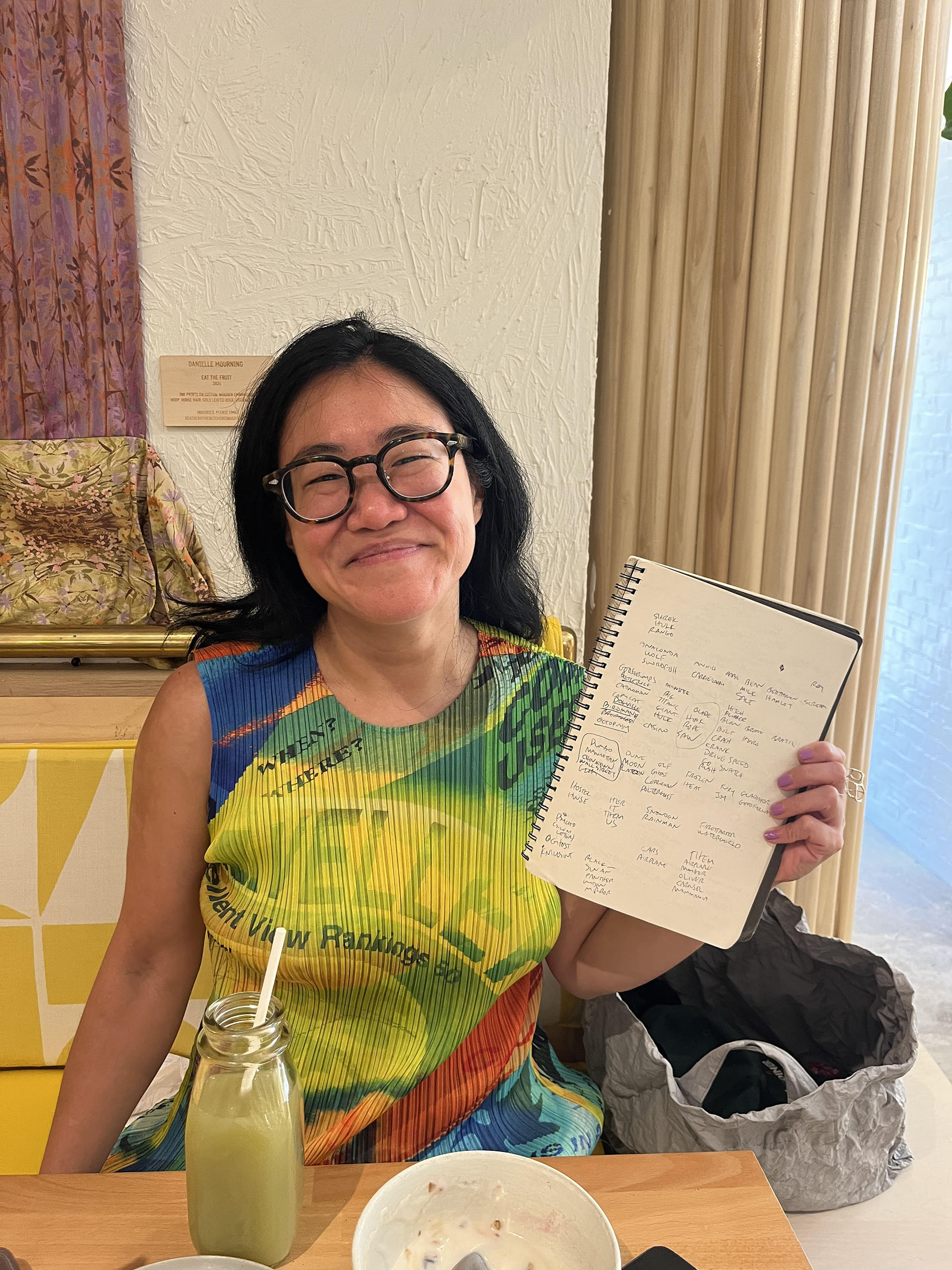

Wyna during her time at ITP

“When I was in college, I always loved making things. I came to ITP because I was really trying to figure out how to do something creative that was also practical at the same time. I’ve always had a confused relationship with art. You know, what IS art? What am I interested in making, and why? I knew I just loved making stuff, so I figured the program was a great way to answer some of those questions for myself.

“The first thing I thought was, ‘I’m going to learn to program! And that’ll be a useful thing that grounds my creative practice.’ I was very excited about it…and then I realized I was not very good at it and also didn’t enjoy it,” she says, laughing. “It was a great lesson!”

“So I pivoted to doing more fabrication, which was already more in line with what I had been doing. I took a Kinetic Sculpture class and a Puppet class—which was wonderful and weirdly rigorous!”

“Ultimately, it was an incredible experience that taught me that the thing I love the most isn’t necessarily the final product of the ‘art’; it’s the process of creating. The figuring out of how to get from here to there, the discovery, the journey of it all. That’s what resonates with me the most.”

Then, Wyna excitedly launches into telling me about her thesis project at ITP: studying the infinite possibilities of polyhedra.

“Through my classes, I started to become really interested in the idea of structure and form, specifically the Platonic solids (three-dimensional shapes whose faces are identical regular polygons). They’re fascinating! Even though there are an infinite number of regular polygons, there are only five Platonic solids, and they’re made up of just three regular polygons: the equilateral triangle, the square, and the pentagon. Plato used those five solid shapes to describe the geometry of the universe. I loved thinking about the relationship between the infinite complexity of shapes and these elemental units!"

My takeaway was this: Wyna is fascinated with the multi-faceted. She sees how something can be multiple things simultaneously. It’s easy to see how the structures that informed her senior thesis have transformed into the 16-word, 4-group panel that Wyna puts together every day for us to solve. Each word has multiple meanings, forming complex possibilities and structures—and no two structures look the same in anyone’s head!

So how does it all come together for her?

“I experience making puzzles in a similar way to solving them,” she says. “When you’re solving a puzzle, you’re trying to get into the puzzle-maker’s head and understand what they’re thinking. Creating a puzzle, though, you’re almost trying to live inside the solver’s head and imagine it from their perspective. They’re two sides of the same process; it’s a very process-driven thing, which is probably why I’m so drawn to it.”

She starts to show me the way she keeps track of each week’s puzzles—a Google Sheet—and mentions her notebook of ideas that she carries around with her. At this, she pulls out a giant sketchpad full of blocks of words. Should the New York Times ever create a museum of historical NYT ephemera, this must surely be featured prominently.

“Google Sheets is great because it lets me move words around and mix and match, but there’s still a lot of satisfaction in just writing things down,” she says, holding the book up for me to see.

Like many artistic careers, Wyna’s work seems to be incredibly passion-driven. She genuinely has fun with it, and there’s a childlike excitement as she describes the process of building a puzzle. I ask Wyna about her history with puzzling, and if it was a big part of her childhood.

She nods emphatically. “Oh yeah, it’s something that’s super obvious to me in retrospect. When I was a little kid, my mom bought me all these anthologies of Games Magazine. A lot of things were illustrated, or some of them were image puzzles, and most of them were way too hard for me at that age (I think I was eight or younger). I would read the puzzles and then look at the answers and just fell in love with the visual vocabulary of it all.

“After that, I forgot about the books for a long time. I started doing crossword puzzles in my 20s and got really into them. I remember going back to my parents’ house one day and seeing these old books that I had as a kid, and I opened them up again and saw the bylines and I recognized the names! It made me tear up a little bit—I was like, I know this person! And this person!

“It was nice to see and realize, ‘Oh, of course, this was always there inside me.’”

As we wrapped up our conversation and after I had turned off the recording app, Wyna said something to me that I’ll never forget.

I had asked her earlier in our conversation what she might say to someone interested in applying to ITP. She spoke enthusiastically about how formative the program had been for her and what a wonderful experience it was for her to get to explore and learn in that environment. As we got up to leave, though, she paused and said:

“You know what I would actually say to students at ITP and Tisch in general?

“Take what you love seriously. We all have interests and pursuits, and it can be easy to push something aside and tell yourself it’s not that important. But if it’s something you love, or even something that interests you, it’s worth pursuing. Take what you love seriously, and others will too.”

For those pursuing a career in the arts, there is no one “normal” path. Everyone takes a different route to build their career, taking a million different steps in different directions—but no way is wrong if you’re pointing yourself in the direction you want to go.

Wyna’s journey illustrates the importance of connecting with one’s passions. By pursuing what she loves, she not only contributes to the vibrant world of word games but also inspires others to take their own interests seriously, reminding us all that every path—no matter how winding—can lead to unexpected and fulfilling connections. ♦