Kelli Anderson

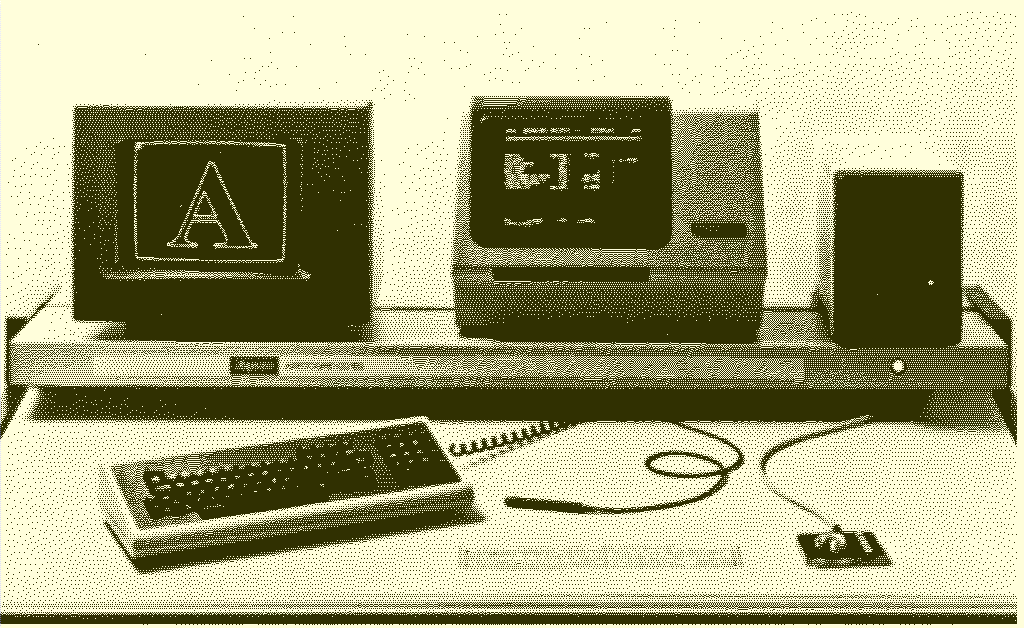

When we see the shape of an uppercase serif letterform, we may subconsciously be reminded of the Roman Empire. What we may not consciously realize is that this association has its roots in the technology used to make these letters, thousands of years ago. Serifs are a wedge-shaped artifact that occurs when a chisel hits stone—the tool used by the Roman Empire to carve their letterforms into monuments called capitals (now a word synonymous with “uppercase” due to this same history.) Though some debate exists among historians, it is widely believed that “capital” letters get their geometric shape from the constraints of the tool of the chisel itself. To understand how the wide stylistic variety of letterforms arrived in our font library (and to understand where our own hazy associations with letterforms originate), one must look to the technology which produced them. From the exigencies of the sign painter’s brush to the psychedelic warping of 1960s Phototype to the 8-bit pixel-based typefaces found in 80s video games, letterforms contain the technological history of the world in microcosm. The subtle choices in each typeface’s form bear the imprint of their moment’s philosophical, technological, and visual conditions, capturing an era’s zeitgeist with a miraculous economy of expression. The letters that we use today are more than 2,000 years old—persisting longer than any other artifacts in common use—but have undergone dramatic fluctuations alongside tech’s major physical transitions from stone to paper to metal to celluloid to digital information. Parallel to this technological history, letters shifted context from cuneiform to letterpress to Linotype to phototype to digital screens in a continual reinterpretation of the the fundamental question “what is a letter?” In the 1970s, technologists and computer scientists found themselves grappling with this same fundamental question as they carried letterforms over into the digital realm: What are letters? Are they fixed visual information? Or are they an idea—a set of executable, gestural instructions? Are letters best understood as reconfigurations of a set of modular parts— building-block components rather than the choreographed gestures of calligraphy? Are they the organic product of the human hand or the output of a system? Early digital technologies wagered “is this what computers are for?” with typefaces in tow—choosing which aspects of the old analog world to reconstruct—in deciding what attributes to port-over. The world we live in today has been impacted by how technologists answered these questions. Questions which, just as easily, could have been answered differently. This course will begin from a place of reflection on our own lived associations with typographic morphology. We will then explore the possible technological origins of those associations while reflecting upon how [what seemed like] tiny digitization decisions delivered us the typographic reality we inhabit today. Students will be asked to look to history for “reasons” for typographic form (which is fun!) But we will also practice looking to history for alternate futures—to examine the “dead ends” that might have otherwise been and daydream about where these paths lead. Typographic technological history offers a manageable jumping-off point for such a thought experiment. This thought experiment scales up to larger problem-solving (and conceptualization) skills related to understanding the implications and effects of tech.