I’ve always had a significant amount of social anxiety which puzzled my mother, who seemingly has none at all. Everything that makes me want to run away—meeting new people, big parties, small talk—appears to be effortless for her. So it was with great glee and relief that I learned about The Entertaining Survival Guide: A Handbook for the Hesitant Host. This book was a gift from my dad to my mom when they were newly married. She was too nervous to have guests over and he bought her the book as a step-by-step guide to help her get through their first small dinner party. I poured over the book, published in 1985, trying to imagine my mom nervously rehearsing the proper way to word an invitation or offer a drink.

Parties terrify me. Especially ones with many guests I don’t know. The thought of being trapped as the host in a party makes me feel absolutely queasy. As the host, you are most responsible if people don’t have a good time. In a sense, artificial intelligence has felt like the party of the moment. To join a party is to agree, in part, to the explicit and implicit rules and social contract. A similar sense of unease and anxiety exists for me at this AI party. Who is the host here, who is responsible? My art practice consists of making my worst fear scenarios into reality. Out of this particular nightmare, the project 24 hour HOST was born.

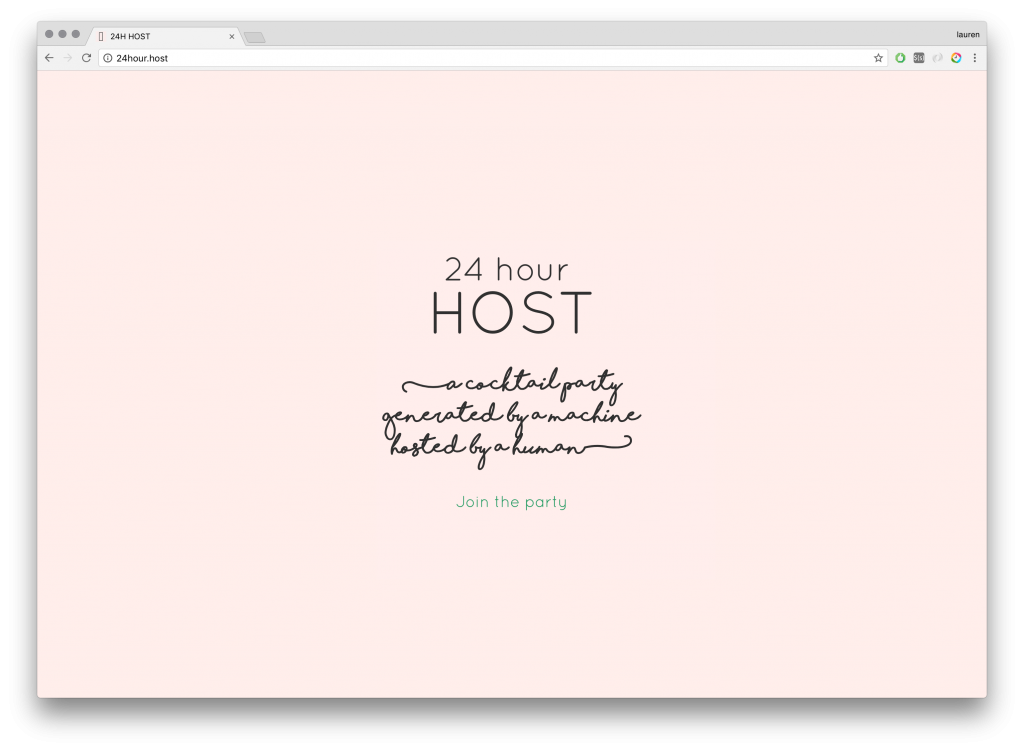

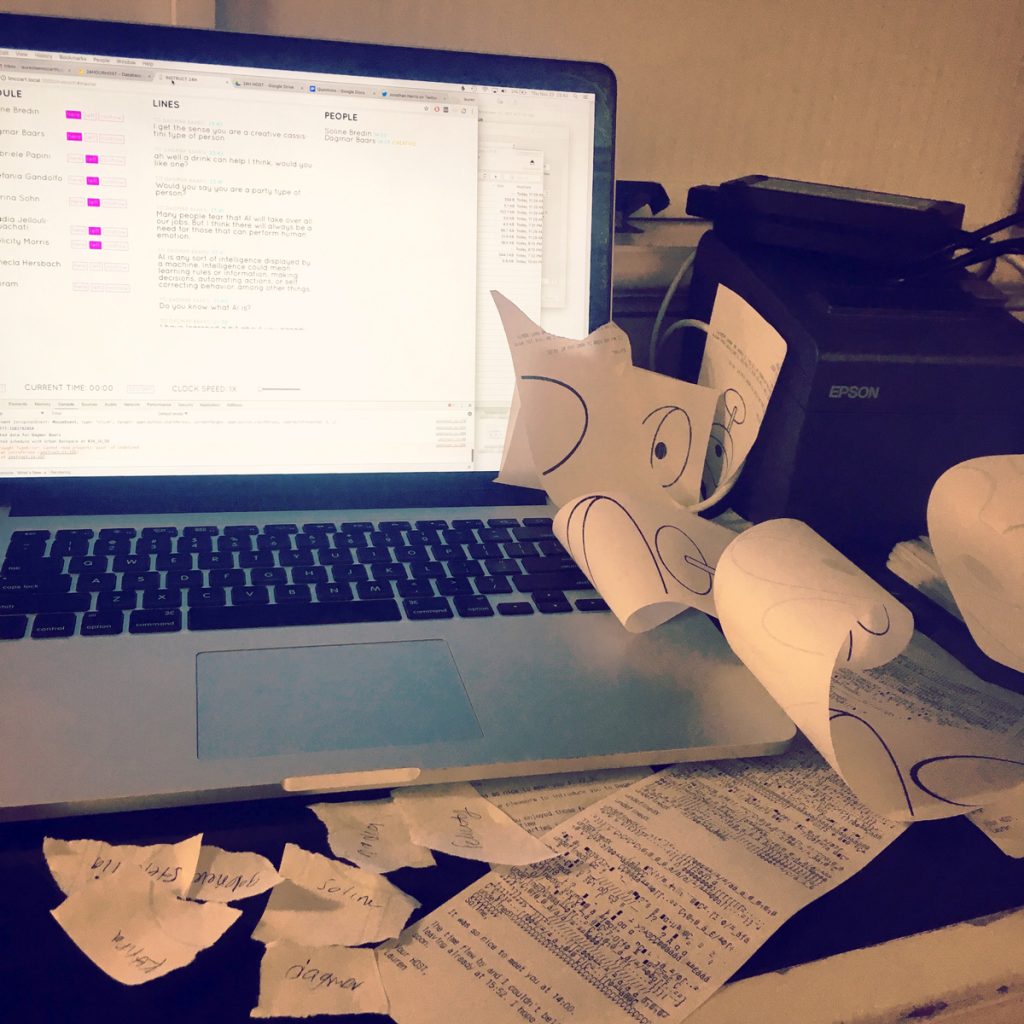

Image of website designed by 24h HOST collaborator, Casper Schipper

24h HOST is a small party that lasts for 24 hours, driven by artificial intelligence that automates the event and is embodied in a human HOST. Prior to the performance, guests register to attend via a website. Their online social identity is scraped and analyzed, and they are assigned an optimal time at which to arrive. Every five minutes throughout the party’s duration, one guest departs and a new guest arrives. I am the host.

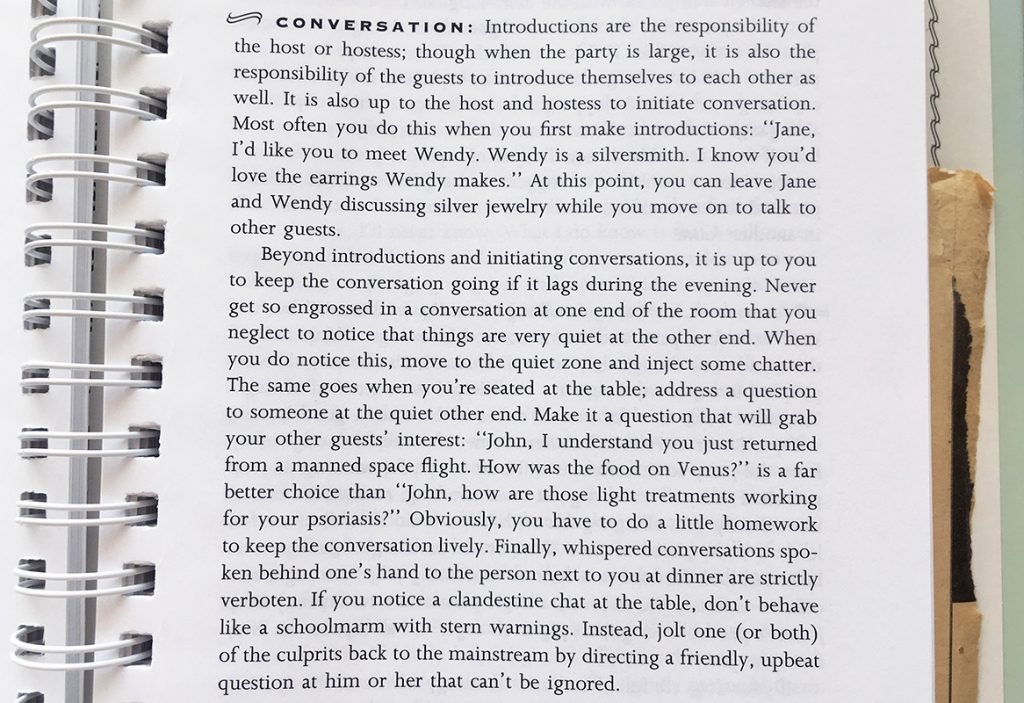

One of my favorite lessons from The Entertaining Survival Guide is how to give the appropriate response when a guests offers help at your party. I am instructed to respond, “How kind of you, but I think I have everything under control.” A good host is one that is in control—of her home, of her guests, of the conversation, of herself.

In the case of computer networks, the term host refers to a device on the network that offers services, resources, and data to users that connect to it. A reliable host is easy to connect to, has little downtime, and keeps the network flowing. I imagined channeling this version of host, offering myself as the always on, connected provider.

Upon entering the 24h HOST party, an AI system analyzes each guest, and determines the proper drink, series of introductions, and conversation points to keep them them engaged. Directions and talking points are communicated to me via an earpiece, and I deliver them with a human touch.

Along with verbal introductions and conversation, the software occasionally directs me to offer the guests physical objects. The proper object is determined based on the computed personalities of the guests in an interaction. The blank gray objects suggest possible usages through their form but function as open-ended prompts. Often the guests wear the objects, perform with them, or improvise small rituals around them. Like any other technology, the objects offer an excuse for deviation in behavior, a symbol of breaking from normal expectations and patterns. While I act as human interface for the AI, the objects provide a technological interface for people to tap into their human intuition for playful behavior.

The performance’s conceit is based on the hypothesis that as algorithms begin to optimize nearly every interaction and aspect of our lives, a last remaining role for people may be performing the emotional labor to act as human interface to AI systems. We may seek the efficiency and optimization of algorithms, but we will still desire the emotional experience of interacting with humans. While we may worry about AI taking over jobs, human caregiving is actually the fastest growing job sector in the country, increasing at a rate of five times that of any other job sector. We will still want to be greeted with a smile, held in an embrace, led by the hand of another person. In this performance, my role is to serve as the human vehicle for the AI’s directions, to deliver them with real emotion and awareness of the person in front of me.

In biology, a host is an organism that harbours another guest, often providing shelter or other resources. The host is usually larger, stronger, or more dominant than its guest. I wonder whether the AI voice in my ear represents a parasitic guest, that is, one that benefits at the host’s expense, weakening it, and perhaps eventually destroying it completely. Or is it possible that we might develop a mutualistic relationship, me and the software adapting to each other and growing together?

The performance begins with my nightmare, and I wonder if the addition of AI makes it easier or more terrifying? I want to believe that having a software system analyzing and aiding my interactions will make things smoother. But now I have two anxieties—the possibility of my personal failure as host, as well as the possibility of software failure due to a bug I may accidentally program. Having software drive me means the host and party can transcend the normal human limitations and durations. Over the course of 24 hours, I wonder which will fail first. As their host becomes more depleted, do the guests begin to see the AI laid bare without human interface, or through the struggling exhaustion is the most human part actually revealed?

At the end of the performance, each guest is printed a receipt documenting the various social and material transactions that took place during their time at the party. Of the hundreds of rotating guests, only one belligerent guest refuses to leave when I let him know his time is up. Unfortunately, I failed to build this scenario into the software and I was left on my own to deal with this glitch.

Everyone else follows the instructions of the host perfectly, no matter how absurd they become. Is it the social rules or the software that keeps them in order? These dual systems of control represent one of the biggest threats of artificial intelligence. We’re building programs to determine the future, based on data that reflects the bias of our current world. There is an opportunity here to reckon with how this data is used and redesign our systems. But this will require that people start questioning, resist their conditioned response to controlling systems, and attempt to rewrite the rules. AI and automation does not relieve us of responsibility, it demands we take more of it than ever.

As guests pass through the entrance, crossing a threshold into the performance, I welcome them at the door. “My software has been learning a lot about you, but I am wondering if you can tell me one thing you think I should know about you.” Some guests have an immediate answer:

“I am one of a set of triplets.”

“I have a lot of luggage.” (“Luggage? Ah, baggage. I see.”)

“I’m not afraid of you.”

In others, a look of confusion and worry arises as they struggle to engage the question and find a suitable answer.

In 24h HOST, I draw a distinction between artificial and human intelligence, but really this is more of a provocation than a fact. As our understanding of AI develops, it will become less meaningful to talk of it as one versus the other, and instead look at the ways the two combine to expand our idea of what either may be. A host, whether biological or technological, is a vessel awaiting connection. A guest arrives, takes what it needs, and imbues the host with purpose. Where the whole system ends up depends on what direction the party focuses its wild energy toward. In lieu of a handbook for the hesitant host, we might need to actively guide one another.

24h HOST was commissioned by and had its debut presentation at MU artspace. Its development was supported in part by Sundance Institute’s New Frontier Lab Programs, with a grant from Turner Broadcasting.

- 1 Anne-Marie Slaughter, “The Work That Makes Work Possible,” The Atlantic (March 23, 2016). https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/03/unpaid-caregivers/474894/