Lashi Conservation Park is a photo book project that reflects on the social media induced tourism and its impact on the landscape of Lashi, Lijiang, China.

Yutong Lin

Description

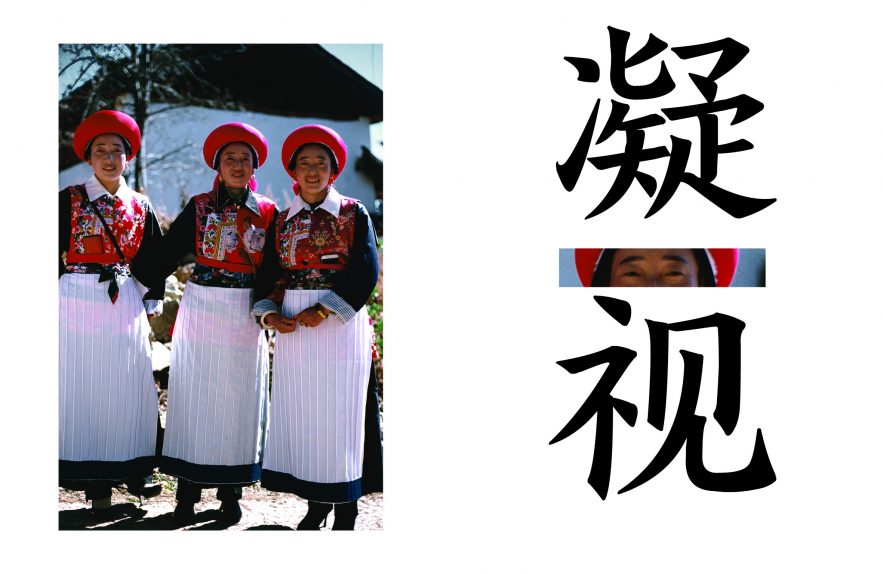

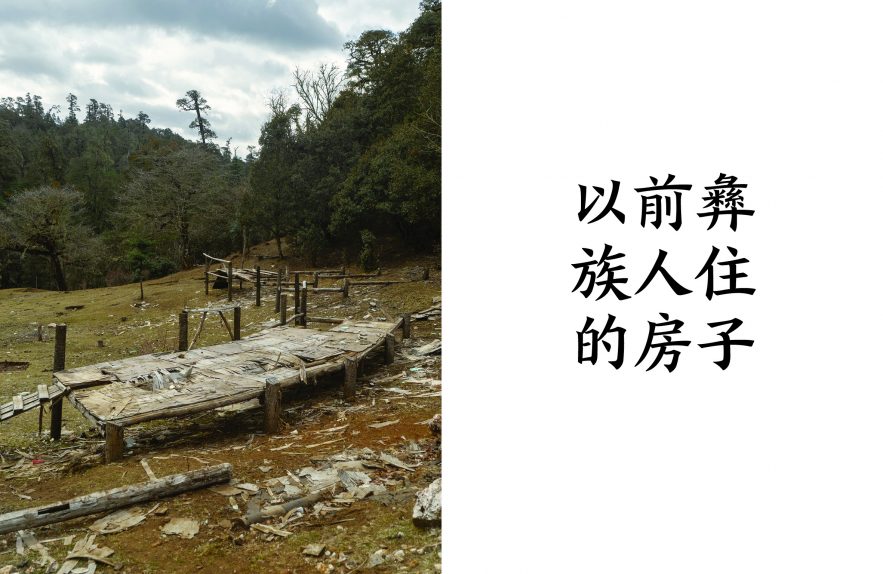

Lashi Conservation Park is a photo book project that walks on the popular horseback riding trips which take tourists up to the source of the Lashi Lake (拉市海) in the mountains. Lashi Lake is located in Lijiang, Yunnan, China. It was a pathway in the ancient Tea Horse Road before the twentieth century, the trading route between Tibet and China. However, the designation of Lijiang as World Culture Heritage in 1997 gradually turned the whole town to a tourist destination, which drastically reformed its landscape and demographics. Lashi Lake now operates more around tourism and its infrastructure than it used to be. Similar to many other famous sites for sightseeing in China, it also has been decorated with “scenic spots” for tourists to take photos for social media posting, which are the sculptures, props, and advertising billboards. To an extent, social media-induced tourism dominates the landscape, rendering the landscape secondary as the backdrop for tourist photography. Therefore, the local and historical context of Lashi is silenced and alienated. The further recontextualization of the tourist imaging on social media forces the landscape to acquire new meanings as embellished souvenirs. Collectively, the online circulation and repopulation of such maintain and reproduce the imagination of a tourist attraction.

The book aims to explore the visual language of the vernacular forms of tourism architecture, investigating the social media tourist’s experience through the photographic delineation of a foreign land. The linguistics of such can be shared and implemented to different places, forming a bizarre visual unity, a sense of “touristy.” Contrasted with more everyday visual encounters in the same region, together, they constitute the hyperreality of Lashi Lake, a sense of deracination from the typology of the land. By taking a camera with me everywhere I go, in a sense, I am also a tourist, eager to take photos when I feel conflicted or don’t know what to respond to what I see. As someone who has family ties to this village, who can’t speak her native Nakhi language, is the action of photo-making and photo documentation of this politicized landscape a form of reconciliation with my identity? Or does the intrusive camera further deepen the gap between me and my people, distancing myself from the water and soil of Lashi.