Introduction

This is an introduction to basic analog output on a microcontroller. In order to get the most out of it, you should know something about the following concepts. You can check how to do so in the links below:

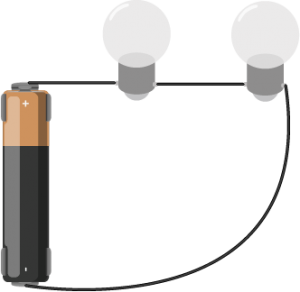

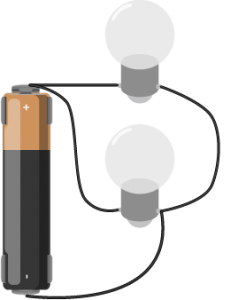

- Electrical circuits

- What a microcontroller is and what it can do

- Digital input and output on a microcontroller

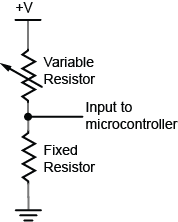

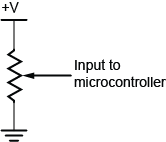

- Analog input on a microcontroller

The following video links will help in understanding analog output:

Analog Output

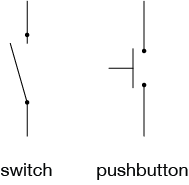

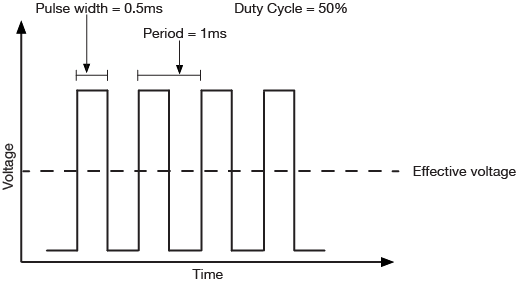

Just as with input, there are times when you want greater control over a microcontroller’s output than a digital output affords. You might want to control the brightness of a lamp, for example, or the turn of a pointer on a dial, or the speed of a motor. In these cases, you need an analog output. The most likely things that you might want to vary directly from a microcontroller are lights, sound devices, or things controlled by motors. For many of these, there will be some other controller in between your microcontroller and the final output device. There are lighting dimmers, motor controllers, and so forth, most of which can be controlled using some form of serial digital communication. What’s covered here are simple electrical devices that can be controlled by a changing voltage. The Arduino and other digital microcontrollers generally can’t produce a varying voltage, they can only produce a high voltage or low voltage. Instead, you “fake” an analog voltage by producing a series of voltage pulses at regular intervals, and varying the width of the pulses. This is called pulse width modulation (PWM). The resulting average voltage is sometimes called a pseudo-analog voltage. The graph in Figure 1 shows how PWM works. You pulse the pin high for the same length of time that you pulse it low. The time the pin is high (called the pulsewidth) is about half the total time it takes to go from low to high to low again. This ratio is called the duty cycle and the total time from off through on to off again is the period. The duty cycle in this case 50%, and the effective voltage is half the total voltage.

Related video: Pseudo-Analog Explained

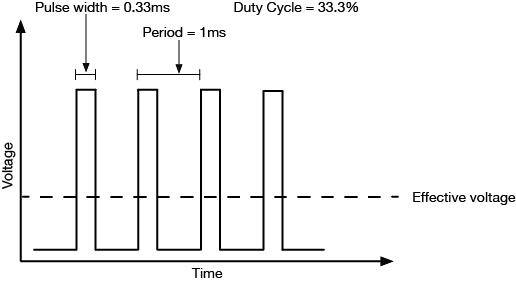

If you make the duty cycle less than 50% by pulsing for a shorter amount of time than you pause, you get a lower effective voltage as shown in Figure 2:

Related video: PWM graphed and see it on the scope

The period is usually a very small time, on the order of a few microseconds or milliseconds at most. The Arduino boards have a few pins which can generate a continuous PWM signal. On the Arduino Nano 33 IoT. they’re pins 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, A2, A3, and A5. On the Arduino Uno, they’re pins 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, and 11. To control them, you use the analogWrite() command like so:

analogWrite(pin, duty);

- pin refers to the pin you’re going to pulse

- duty is a value from 0 – 255. 0 corresponds to 0 volts, and 255 corresponds to 5 volts. Every change of one point changes the pseudo-analog output voltage by 5/255, or 0.0196 volts.

Applications of Pulse Width Modulation

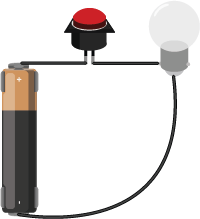

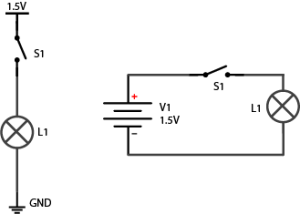

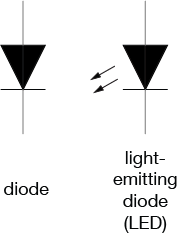

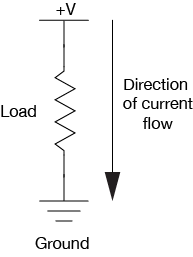

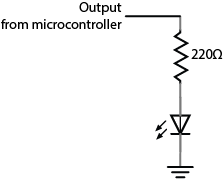

LED dimming

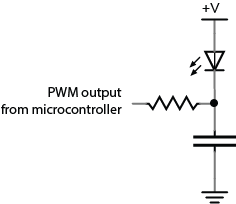

The simplest application of analogWrite() is to change the brightness of an LED. Connect the LED as you did for a digital output, as shown in Figure 3, then use analogWrite() to change its brightness. You’ll notice that it doesn’t change on a linear scale, however.

Related video: See the effect of PWM on the LED

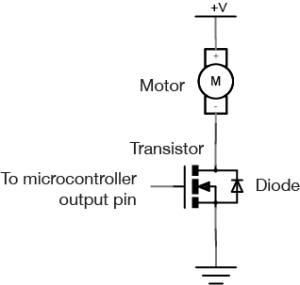

DC Motor Speed Control

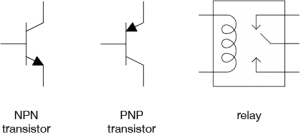

You can vary the speed of a DC motor using the analogWrite() command as well. The schematic is in Figure 4. You use the same transistor circuit as you would to turn on and off the motor, shown in Figure 4, but instead of setting the output pin of the microcontroller high or low, you use the analogWrite() on it. The transistor turns on and off at a rate faster than the motor can stop and start, so the result is that the motor appears to smoothly speed up and slow down.

For more on DC motor control, see the following links:

- DC motor control notes

- Related video: Why use PWM on DC Motors?

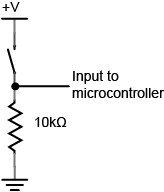

Note: Filter circuits

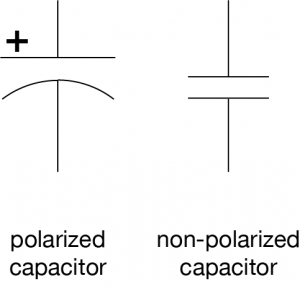

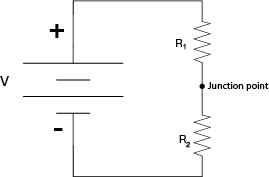

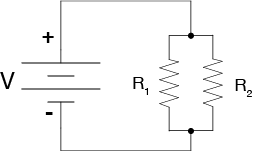

Filter circuits are circuits which allow voltage changes of only a certain frequency range to pass. For example, a low-pass filter would block frequencies above a certain range. This means that if the voltage is changing more than a certain number of times per second, these changes would not make it past the filter, and only an average voltage would be seen. Imagine, for example, that your PWM is operating at 1000 cycles per second, or 1000 Hertz (Hz). If you had a filter circuit that blocked frequencies above 1000 Hz, you would see only an average voltage on the other side of the filter, instead of the pulses. A basic low-pass filter consists of a resistor and a capacitor, connected as shown in Figure 5:

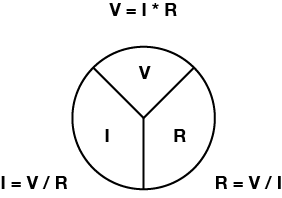

The relationship between frequency blocked and the values of the capacitor and resistor is as follows:

frequency = 1/ (2π *resistance * capacitance)

A 1.5-kilohm resistor and a 0.1-microfarad capacitor will cut off frequencies above around 1061 Hz. If you’re interested in filters, experiment with different values from there to see what works best.

Servomotors

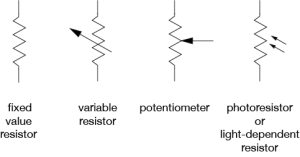

Perhaps the most exciting thing you can do as analog output is to control the movement of something. One simple way to do this is to use a servomotor. Servomotors are motors with a combination of gears and an embedded potentiometer (variable resistor) that allows you to set their position fairly precisely within a 180-degree range. They’re very common in toys and other small mechanical devices. They have three wires:

- power (usually +5V)

- ground

- control

Connect the +5V directly to a 5V power source (the Arduino’s 5V or 3.3V output will work for one servo, but not for multiple servos). Ground it to the same ground as the microcontroller. Attach the control pin to any output pin on the microcontroller. Then you need to send a series of pulses to the control pin to set the angle. The longer the pulse, the greater the angle.

To pulse the servo, you generally give it a 5-volt, positive pulse between 1 and 2 milliseconds (ms) long, repeated about 50 times per second (i.e. 20 milliseconds between pulses). The width of the pulse determines the position of the servo. Since servos’ travel can vary, there isn’t a definite correspondence between a given pulse width and a particular servo angle, but most servos will move to the center of their travel when receiving 1.5-ms pulses. This is a special case of pulse width modulation, in that you’re modifying the pulse, but the period remains fixed at 20 milliseconds. You could write your own program to do this, but Arduino has a library for controlling servos. See the Servo lab for more on this.

Related video: Analog Output – Servo

Changing Frequency

Pulse width modulation can generate a pseudo-analog voltage for dimming and motor control, but can you use it to generate pitches on a speaker? Remember that you’re changing the duty cycle but not the period of the signal, so the frequency doesn’t change. If you were to connect a speaker to a pin that’s generating a PWM signal, you’d hear one steady pitch.

If you want to generate a changing tone on an Arduino microcontroller, however, there is a tone() command that will do this for you:

tone(pin, frequency);

This command turns the selected pin on and off at a frequency that you set. With this command, you can generate tones reasonably well. For more on this, see the Tone Output lab.

Related video: Analog Output – Tone

Ranges of Values

As a summary, Table 1 below shows the ranges of values for digital input/output and analog input/output, which have been discussed in Digital Input & Output, Analog Input, and this page.

| Digital | Input (Digital Pins) | 0 [LOW] or 1 [HIGH] (2^0) | 0V or 3.3V (newer microcontrollers) 0V or 5V (older microcontrollers) |

| Output (Digital Pins) | 0 [LOW] or 1 [HIGH] (2^0) | 0V or 3.3V (newer microcontrollers) 0V or 5V (older microcontrollers) | |

| Analog | Input (Analog Input Pins) | 0 ~ 1023 (<210) | 3.3 / 210 |

| Output (Digital PWM Pins) | 0 ~ 255 (<28) | 3.3 / 28 |