Introduction

In the stepper motor and H-bridge lab, you learned how to control a stepper motor with a dual H-bridge driver, specifically the TB6612FNG. This is not the only driver for controlling a stepper. Step & direction stepper drivers offer a simpler approach, from the microcontroller side. They have just two control pins, one for step and one for direction. They also feature configuration pins that let you set the step pin to move the motor a full step, a half step, or less. This is called microstepping, and you can find stepper drivers that will work as low as 1/256th of a step. This allows finer control over the stepper motor. In this lab you’ll learn how to use a step & direction controller to control a stepper motor.

What You’ll Need to Know

To get the most out of this lab, you should be familiar with the following concepts. You can check how to do so in the links below:

- How to solder up a connector

- Electronic components

- How DC Motors work

- How Stepper Motors work

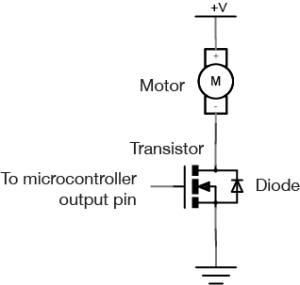

- How to use transistors to control high current loads with Arduino

- It’s useful to know about stepper motor control using an H-bridge for comparison as well.

Things You’ll Need

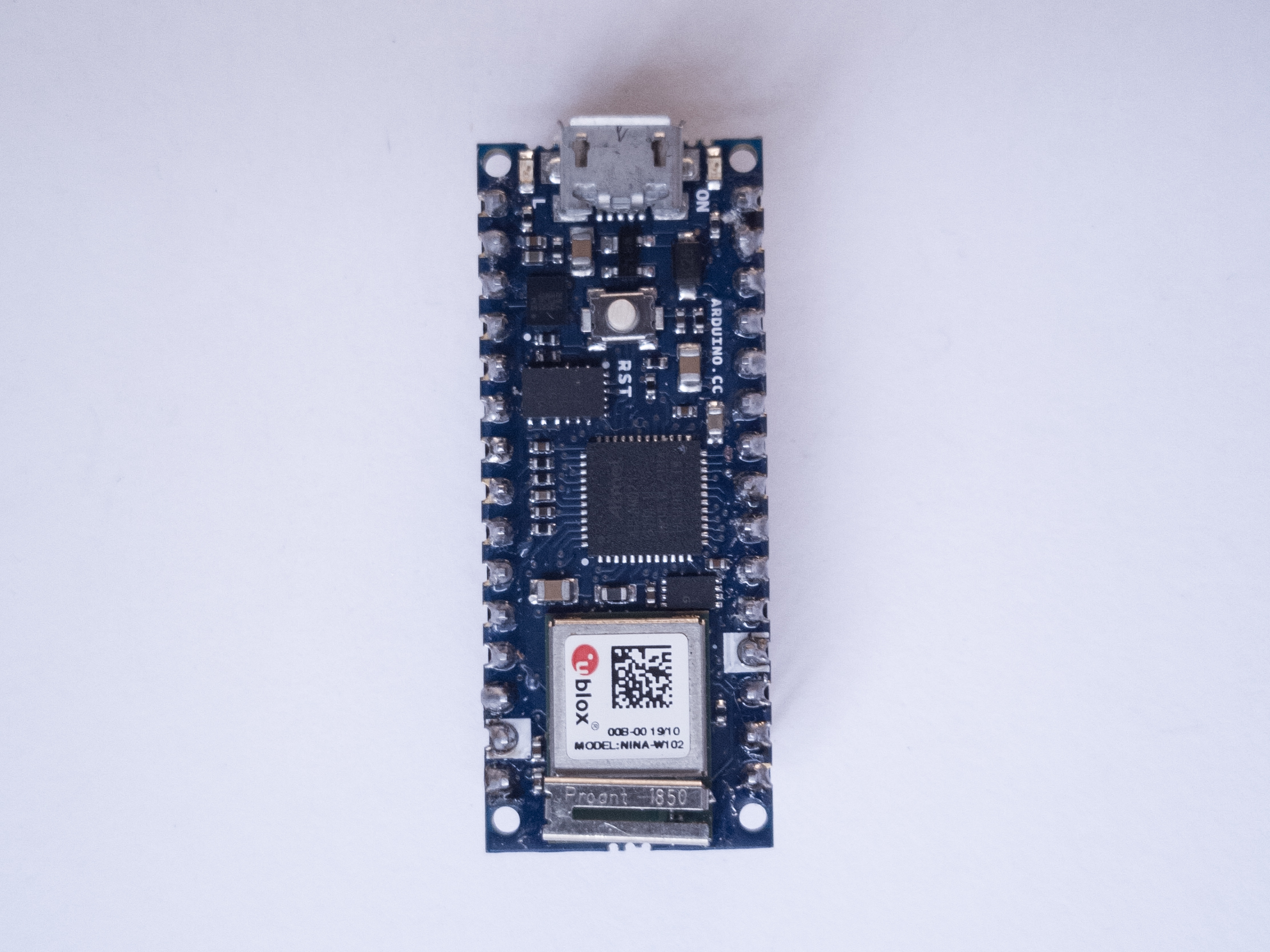

Arduino Nano 33 IoT

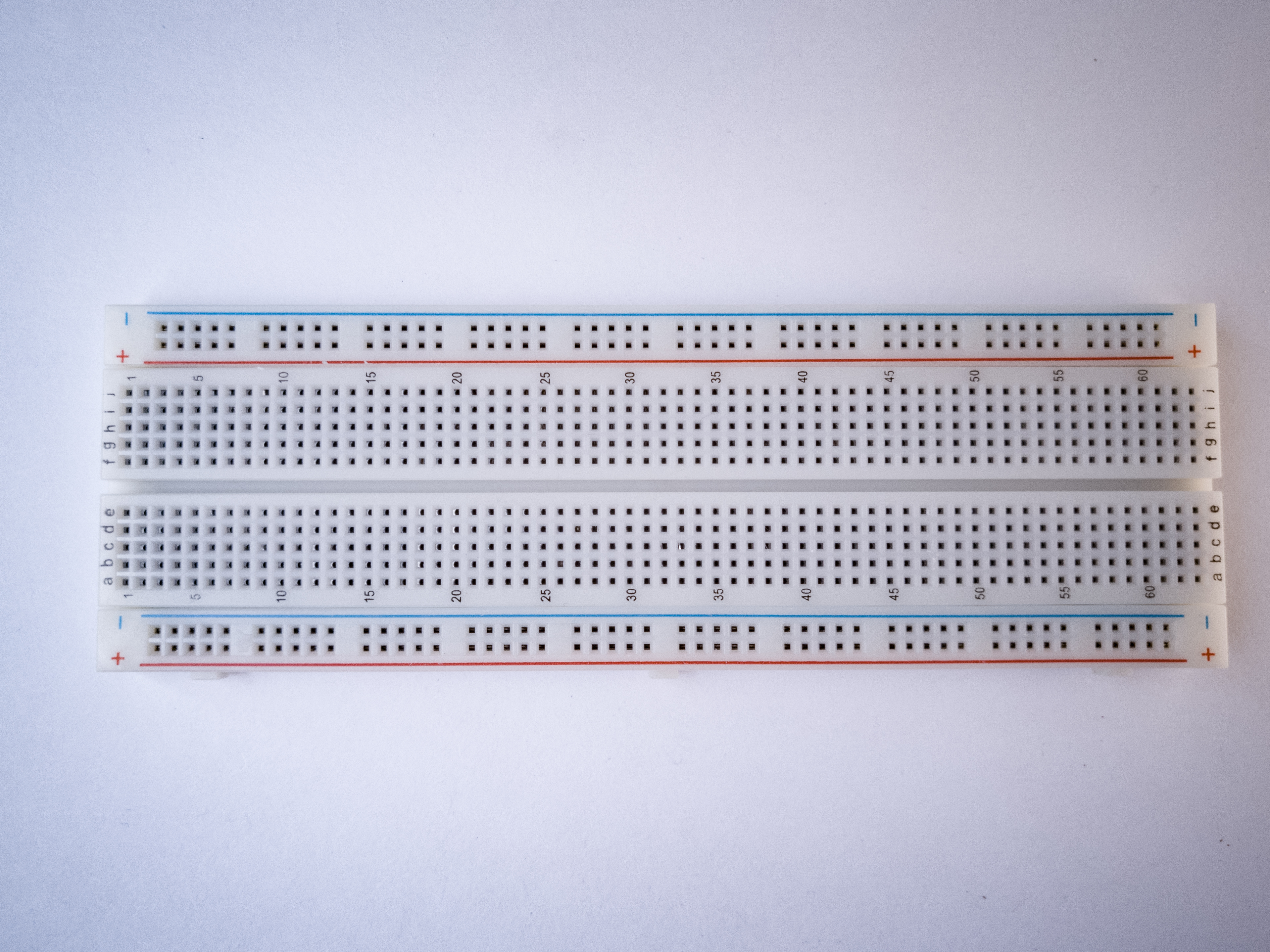

A solderless breadboard with two rows of holes along each side.

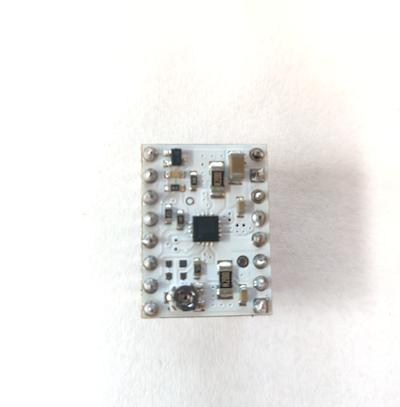

Stepper motor driver model STSPIN220

Flexible jumper wires.

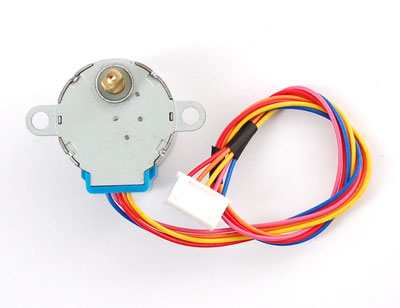

a stepper motor

A DC Power Jack

DC Power Supply

Multimeter. You’ll need this to check the coils and set the motor driver’s current limit.

The motor shown in the images here is a 5V Small Reduction Stepper Motor, 32-Step, with 1:16 Gearing. This motor is a useful starter motor for steppers because it can run on the current and voltage supplied by your Arduino without an external power supply. The driver is a STMicro STSPIN220 on a Pololu breakout board. There are a number of other step & direction motor drivers available if the STSPIN220 doesn’t meet your needs. Control for all of them will be similar to what you see below. In fact, Pololu makes a number of carrier boards for different step & direction drivers, all with the same pin layout. The principles in this lab, and the library used, will work with other stepper motors and step & direction drivers as well, though you will have to make some modifications depending in which parts you are using.

Good Safety Practice

When you’re working with motors, you’re often dealing with high voltage, high current, or both. You should be extra careful never to make changes to your circuit while it is powered. If you need to make changes, unplug the power, make your changes, inspect your changes to be sure they are right, and then reconnect power.

It’s also a good idea to disconnect your motor from your circuit before uploading new code to your microcontroller. Often the current draw of the motor will cause the microcontroller to reset, and cause uploading problems. To avoid this, disconnect your motor before uploading, and reconnect it after uploading.

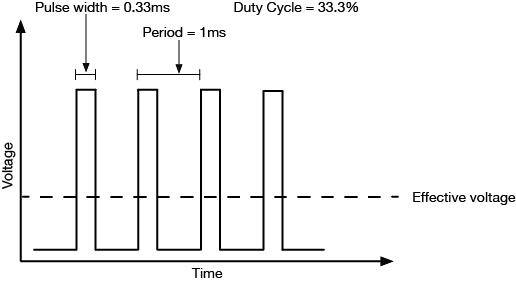

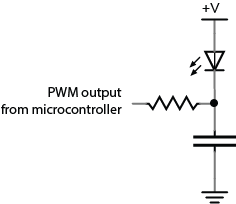

Because motors consume a lot of current when they start up, it’s common to add a decoupling capacitor of 10-100 µF near the voltage input to your driver and/or microcontroller. You’ll see this in the figures below. It will smooth out any voltage changes that occur as a result of the motor’s changing current consumption.

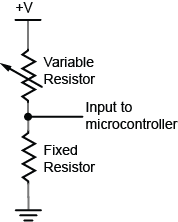

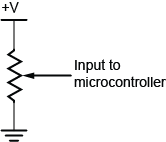

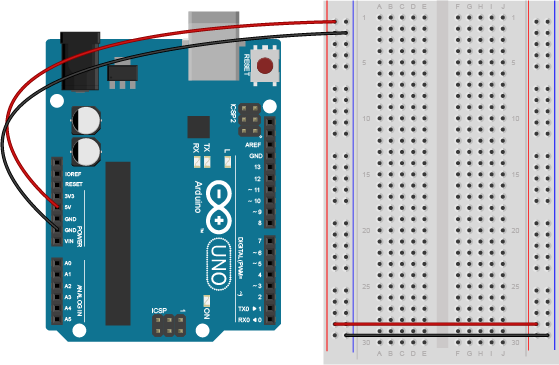

Prepare the breadboard

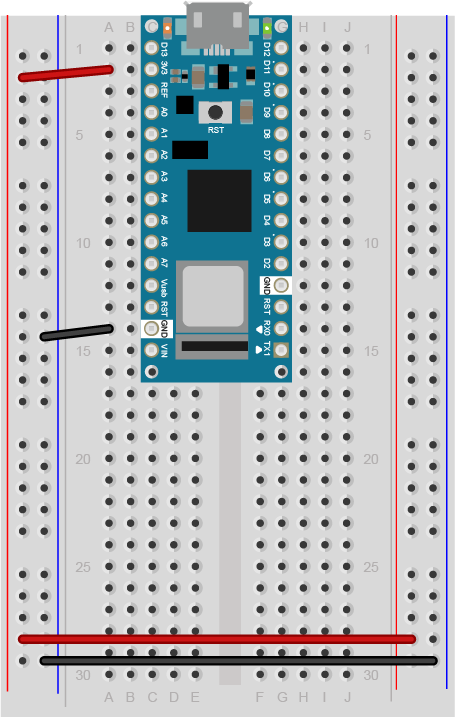

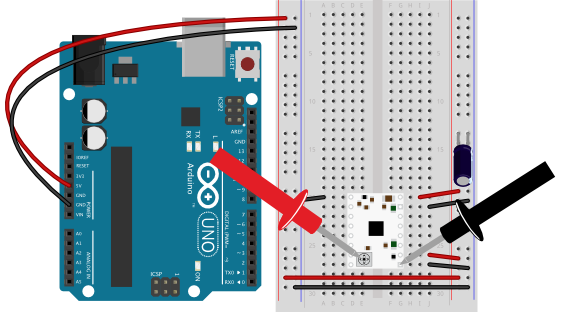

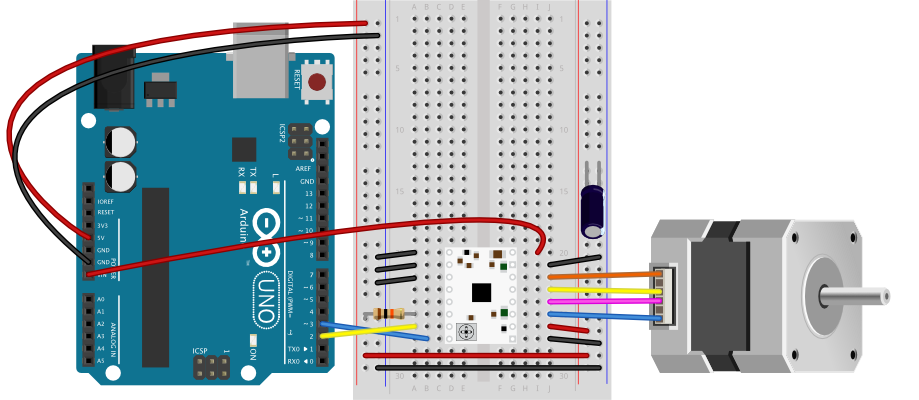

Connect power and ground on the breadboard to power and ground from the microcontroller. On the Arduino module, use the 5V or 3.3V (depending on your model) and any of the ground connections, as shown in Figures 9 and 10.

Figure 9 shows an Arduino Uno on the left connected to a solderless breadboard, right. The Uno’s 5V output hole is connected to the red column of holes on the far left side of the breadboard. The Uno’s ground hole is connected to the blue column on the left of the board. The red and blue columns on the left of the breadboard are connected to the red and blue columns on the right side of the breadboard with red and black wires, respectively. These columns on the side of a breadboard are commonly called the buses. The red line is the voltage bus, and the black or blue line is the ground bus.

Made with Fritzing

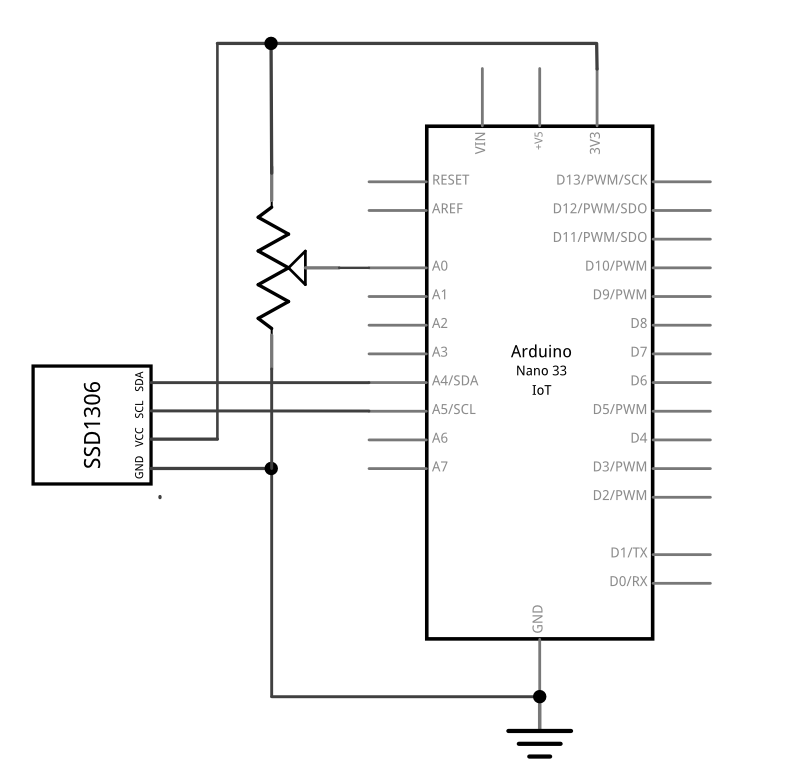

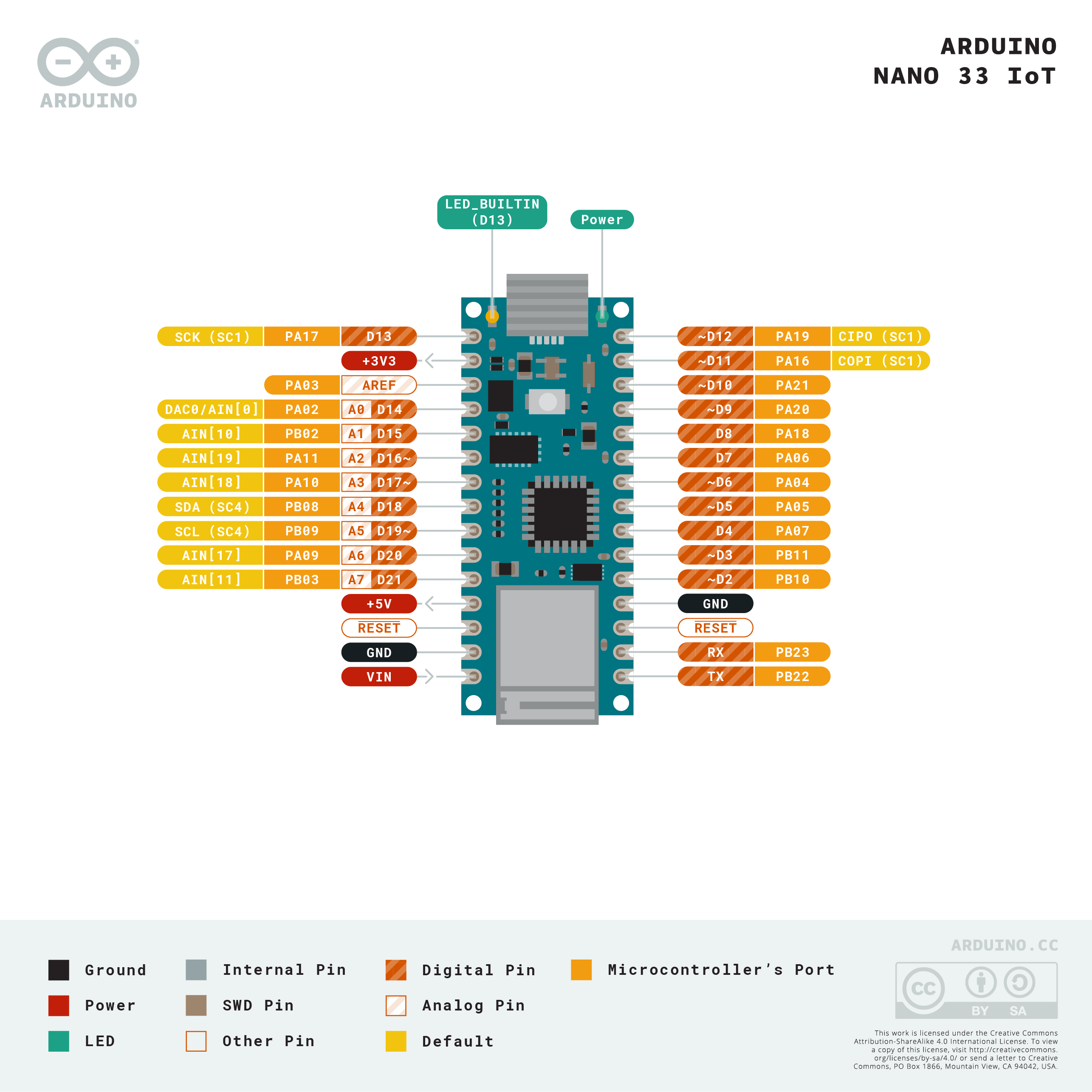

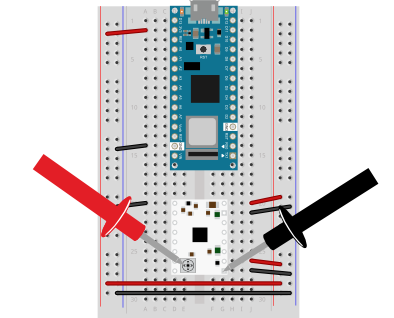

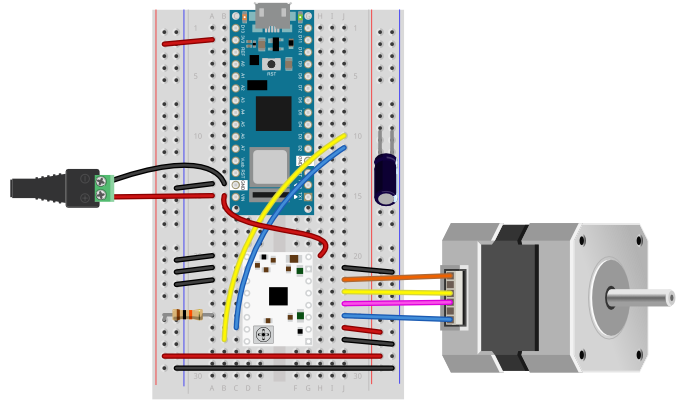

As shown in Figure 10, the Nano is mounted at the top of the breadboard, straddling the center divide, with its USB connector facing up. The top pins of the Nano are in row 1 of the breadboard.

The Nano, like all Dual-Inline Package (DIP) modules, has its physical pins numbered in a U shape, from top left to bottom left, to bottom right to top right. The Nano’s 3.3V pin (physical pin 2) is connected to the left side red column of the breadboard. The Nano’s GND pin (physical pin 14) is connected to the left side black column. These columns on the side of a breadboard are commonly called the buses. The red line is the voltage bus, and the black or blue line is the ground bus. The blue columns (ground buses) are connected together at the bottom of the breadboard with a black wire. The red columns (voltage buses) are connected together at the bottom of the breadboard with a red wire.

How the Stepper Motor Works

A stepper motor is basically two motor coils in one motor, which allows you to turn the motor in steps. For more on this, see this stepper motor page.

The motor shown in this lab, a 5V Small Reduction Stepper Motor, 32-Step, with 1:16 Gearing, is typical of a class of stepper motors you can find using the designation 28BYJ-48. They come in a few varieties. There are 5V and 12V models, and there are versions like the one shown here, that have a gearbox on the top to increase their torque and increase the number of steps per revolution. The un-geared models have as few as 32 steps per revolution. This model has 32 steps per revolution and a 1/16 reduction gear box, giving it 32 * 16, or 512 steps per revolution. You can find models with an even higher reduction as well.

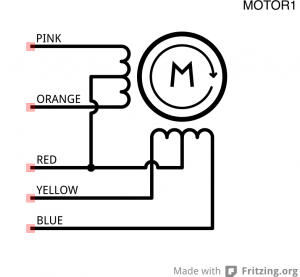

A stepper motor like this one has two coils to control it as shown in Figure 11. Each coil has a center connection as well, and the center connections are joined together, which is what makes this a unipolar stepper. If you don’t connect the center connection, then the motor will work like a bipolar stepper, each coil operating independently. This is how you’ll use it for this exercise. Each coil will connect to one control channel of the motor driver. The pink and orange wires are connected to the first coil. They will connect to one channel of the motor driver, while the yellow and blue wires are the other coil, and will connect to the other channel of the bridge (channel B). In this case, the red wire, pin 1, will not be used.

A bipolar stepper motor typically omit the red wire and just have two independent coils. A bipolar model like this 3.9V NEMA-8 stepper from Pololu would also work with this lab.

Check the Motor Coils’ Resistance

The wiring pattern in Figure 11 is typical, for the 28BYJ-48 motors. Nonetheless, it’s a good idea to check the wiring by measuring the coil resistance. The motor shown here has a coil resistance (impedance) of about 42 ohms. For a bipolar motor, each pair of coils (e.g. blue and yellow, orange and pink) would give you the motor’s rated coil resistance. Since this is a unipolar motor, you should read approximately 22-24 ohms across red and each of the other wires, and about 42-45 ohms across each pair (blue-yellow and orange-pink).

The sequence of the wires on the motor’s connector may vary from one manufacturer to another, so it’s a good idea to measure the resistance, then write down the pin order for reference later on.

How The Motor Driver Works

The STSPIN220 can handle a motor supply voltage from 1.8 to 10V, and it operates on a logic voltage of 3.3–5V. It can control an output current of 1.1A per coil.

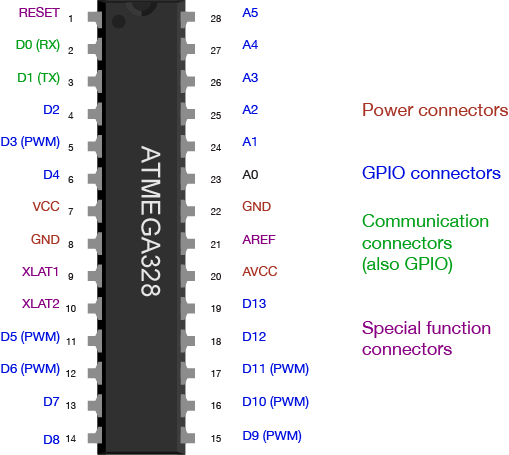

The motor driver has the following pins. The pin numbers shown here are for the Pololu breakout board. The pins are numbered here in a DIP fashion, in a U-shape from top left to bottom left, then bottom right to top right. The list below describes the pins in numeric order.

- Enable – enables the driver when you take it LOW and disables it when you take it HIGH. The breakout board pulls this pin LOW by default, so if you don’t connect it, your motor should work fine.

- Mode 1 -Configuration pin for microstepping

- Mode 2 – Configuration pin for microstepping

- 1 – not connected by default

- 2 – not connected by default

- Standby – Puts the the driver in a low-power standby mode and disables the motor when you take it LOW.

- Step/Mode 3 -When you pulse this pin HIGH then LOW, the motor moves forward one step. Also functions as a configuration pin for microstepping.

- Dir/Mode 4 – When you pulse this pin HIGH, the motor in one direction when you pulse the step pin. When you take it LOW, it moves in the other. Also functions as a configuration pin for microstepping.

- Ground – ground

- Vcc – Logic voltage. Connect this to the Vcc of your microcontroller, for example 5V for an Uno or 3.3V for a Nano 33 IoT

- A1 – Motor output coil 1

- A2 – Motor output coil 1

- B2 – Motor output coil 2

- B1 – Motor output coil 2

- Ground – ground

- VMOT – motor voltage supply input, 1.8-10V.

Connect the Motor Driver and Set the Current Limit

Many step and direction drivers like the STSPIN220 have an adjustable current limit built into the driver. This lets you set the maximum output current to match the current your motor needs. Pololu has a video explaining this process. This is important, because if you don’t set the current limit correctly, you risk damaging the driver and the motor. The details follow here. You have to know your motor’s desired current, then you use a formula to work out the value of a current limiting resistor for the driver.

If you have the motor’s current from the datasheet (110mA for the motor listed above), then you’re all set. If you don’t, you can calculate it from the motor’s voltage and the resistance of its coils. First, measure the resistance of one coil, as explained in the stepper motor lesson. Remember that current, voltage, and resistance are all related using the formula

Voltage = Current * Resistance

For example, if your motor’s coil resistance reads 45.4 ohms, and it runs on 5 volts, then the current = 5 / 45.4, or about 110 mA.

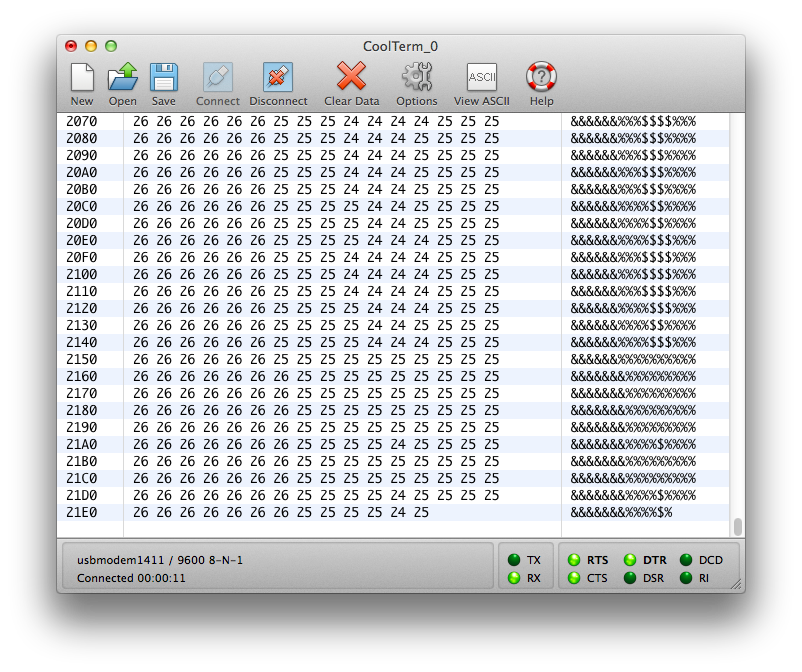

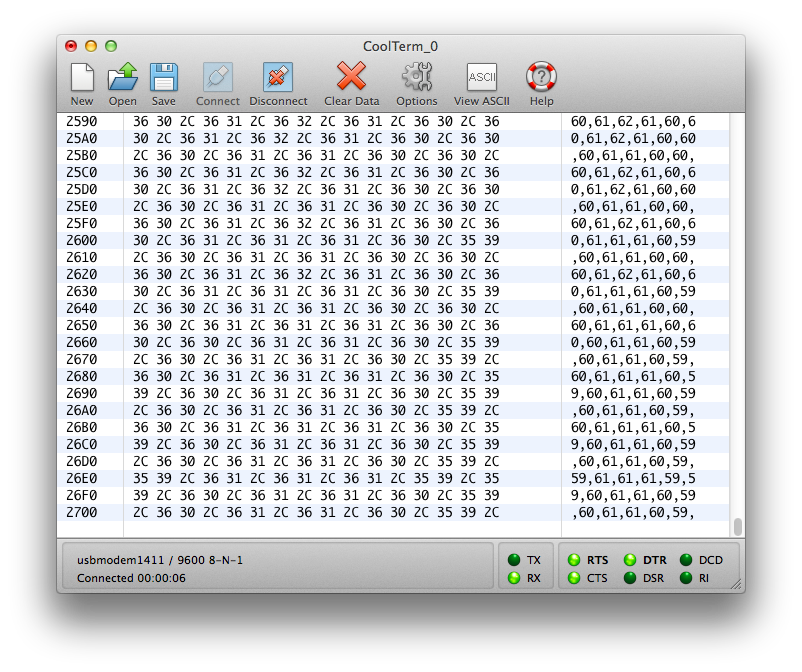

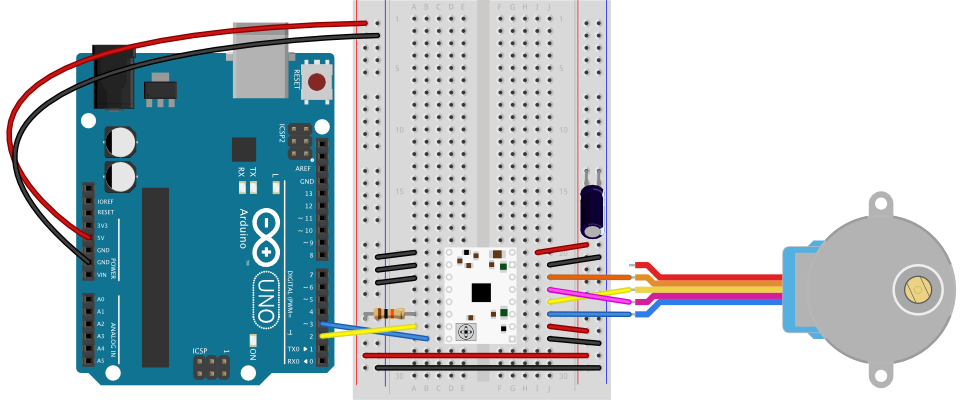

To prepare for this, connect the STSPIN220 board as shown in Figures 12 and 13. Do not connect a motor yet. You’re powering the board up just so you can set the current limit.

The board is mounted straddling the center row of a breadboard, and the following pins on the STSPIN220 are connected:

- Pin 1, Enable – connected to the ground bus on the left side of the breadboard

- Pin 9, Ground – connected to the ground bus on the right side of the breadboard

- Pin 10, Vcc – Logic voltage. Connected to the voltage bus on the right side of the breadboard

- Pin 15, Ground – connected to the ground bus on the right side of the breadboard

- Pin 16, VMOT – Connected to the voltage bus on the right side of the breadboard. If you were using an external power supply for a higher voltage stepper motor, you would connect this to the positive terminal of the external supply.

Pololu makes its step & direction driver boards with a built-in trimmer potentiometer to act as a current limiting resistor. It’s usually at the bottom of the board. Calculating the value of this resistor is explained in detail in section 6 of the STSPIN220 data sheet. Pololu have summarized it in a formula below.

To set the current limit, you power up the driver without a motor attached and measure the voltage between this trimmer pot and ground. Then you turn the trimmer pot until you read the reference voltage for the current limit, or VREF. In Figures 12 and 13 there are multimeter probes shown, used to measure voltage. The red probe (positive) is touching the trimmer pot on the STSPIN220 and the black probe (negative) is touching pin 9, the ground pin. Set your multimeter to read voltage in the range of your Vcc (3.3 to 5V), then touch the leads to the trimmer pot and to ground as shown in figures 12 and 13. You should get a voltage between zero and Vcc. Then turn the pot with a small screwdriver until you read your desired VREF.

For the STSPIN220, the current limit formula is as follows:

Current= VRef * 5

Rearranging that to get the voltage on the trimmer pot:

VRef = Current / 5

So, if your desired current is 110 mA, or 0.11 A, then VREF = 0.11 / 5, or 0.022V. Turn your pot until the voltage reads that value (or whatever you calculated it to be for your motor) and you’re ready to go. The trimmer pot is small and difficult to turn, so try to get in the general range of your VREF. You probably won’t get it exactly. If you find the motor or the driver is excessively hot while running (if you can’t touch it comfortably) then you should re-adjust the trimmer pot to get closer to your proper VREF.

You can now disconnect from your power supply, add the motor, and reconnect to program the microcontroller.

Connect the Motor

This motor nominally runs on 5 volts. It will run as low as 3.3 volts if you give it enough current (about 110 mA). It can run on the current supplied to an Uno or Nano 33 IoT’s USB connection. Ideally, though, you should run it from an external power supply, as described later in the lab.

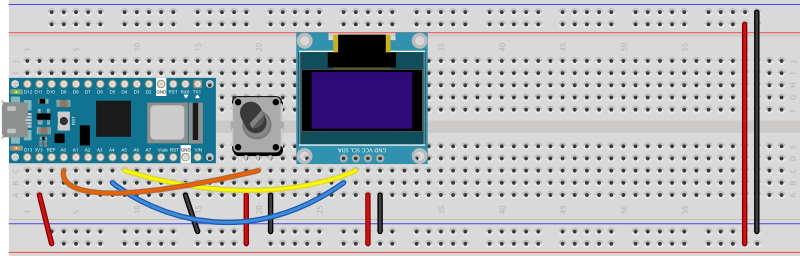

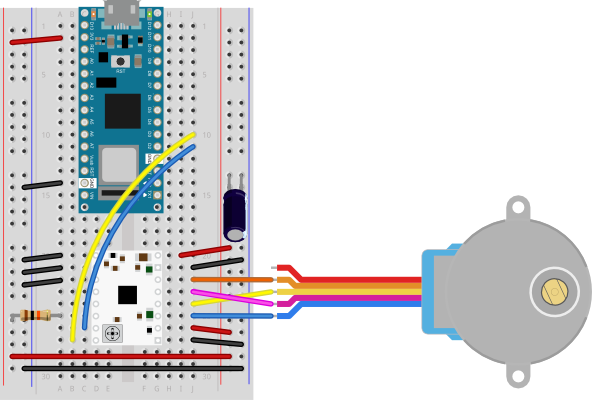

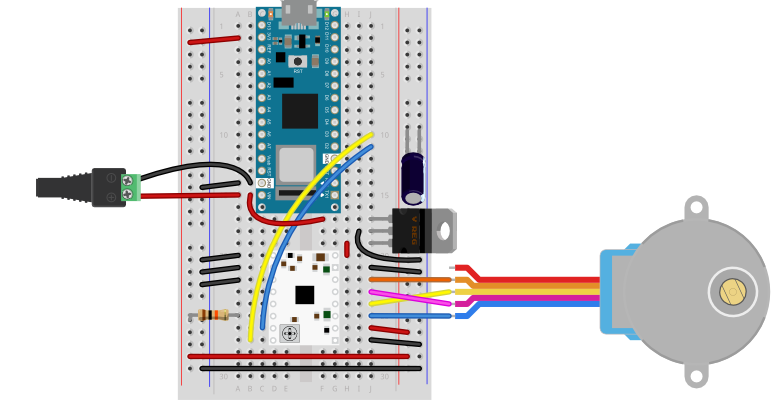

To finish your stepper motor circuit, connect the motor according to Figures 14 through 16.

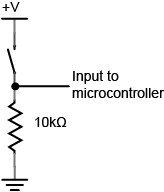

Table 1 below describes the pin connections for the circuit. The STSPIN220 is still connected to the breadboard as shown previously in figures 12 and 13, but now the motor’s coils are connected to pins 11 – 14 of the motor driver and the driver’s step and direction pins (pins 7 and 8 respectively) are connected to digital output pins 2 and 3 of the Arduino, respectively. The two mode pins (pins 2 and 3) are connected to ground, and the standby pin (pin 6) is connected to Vcc through a 10-kilohm resistor.

| Motor Driver Physical pin number | Pin function | Circuit Connection |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enable | Ground |

| 2 | Mode 1 | Ground |

| 3 | Mode 2 | Ground |

| 4 | 1 | not connected |

| 5 | 2 | not connected |

| 6 | Standby | 10-kilohm resistor to Vcc |

| 7 | Step | Arduino digital pin 2 |

| 8 | Direction | Arduino digital pin 3 |

| 9 | Ground | Ground |

| 10 | Vcc | Arduino Vcc (3.3 or 5V) |

| 11 | A1 | Motor coil 1 |

| 12 | A2 | Motor coil 1 |

| 13 | B2 | Motor coil 2 |

| 14 | B1 | Motor coil 2 |

| 15 | Ground | Ground |

| 16 | VMOT | Arduino Vcc if using USB power. Arduino Vin if using an external power supply. |

Made with Fritzing

Once you have the motor and the driver connected, you’re ready to program the microcontroller.

Program the microcontroller

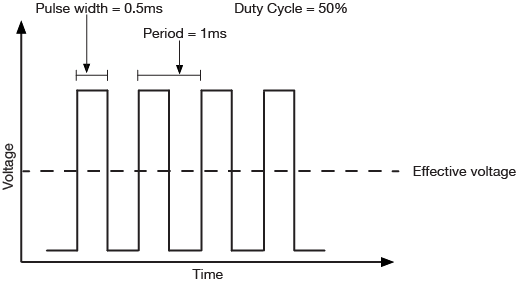

You don’t need a library for a step and direction controller, though there are several out there, to do things like ramp the speed up and down, ease in and out, and so forth. All you need to do to move the motor is to set the direction pin, and to pulse the motor high then return to low. A 3-millisecond pulse will do the job reliably. If you need more speed, you can try reducing this down to 2 or even 1ms, once you know the motor’s working properly.

Regardless of what motor driver you are using, the first thing you should do after wiring up a stepper motor is to write two test programs, one to test if it’s stepping, and one to test if it can rotate one revolution in both directions.

For your first program, it’s a good idea to run the stepper one step at a time, to see that all the wires are connected correctly. If they are, the stepper will step one step forward at a time, every half second, using the code below.

const int stepPin = 2;

const int dirPin = 3;

void setup() {

pinMode(stepPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(dirPin, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

// motor direction:

digitalWrite(dirPin, HIGH);

// step the motor one step:

digitalWrite(stepPin, HIGH);

delay(3);

digitalWrite(stepPin, LOW);

// wait half a second:

delay(500);

}

Once you’ve got that working, try making the stepper move one whole revolution at a time using the code below:

const int stepPin = 2;

const int dirPin = 3;

const int stepsPerRevolution = 512;

bool direction = HIGH;

void setup() {

pinMode(stepPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(dirPin, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

// motor direction:

digitalWrite(dirPin, direction);

// move one revolution :

for (int step = 0; step < stepsPerRevolution; step++) {

// step the motor one step:

digitalWrite(stepPin, HIGH);

delay(3);

digitalWrite(stepPin, LOW);

delay(1);

}

// wait half a second:

delay(500);

// change direction:

direction = !direction;

}

When you run this code, you should see the motor turn one revolution, wait half a second, then turn one revolution in the other direction.

My motor’s only going one direction!

If you find that the motor only turns in one direction, you probably have the pin connections wrong. It could be that you got the order wrong. Try rearranging the order of the pins. Disconnect power each time you try changing your connections. First, try swapping the two pins on each coil (e.g. blue and yellow, pink and orange) and run it again. If that fails, swap one wire from one coil for one wire from the other coil. Keep trying variations until your motor goes around in one direction, then goes around in the opposite direction.

Unipolar Stepper Control

The steps above showed you how to control your motor as a bipolar stepper, but the motor shown is actually a unipolar motor. Remember the red wire you didn’t connect? That wire connects the two coils and can act as a common power source or ground wire. To use the motor as a unipolar motor, try connecting that wire (wire 1) of the motor to the Vin power supply from the DC power jack. You should see that there’s not a lot of difference.

Attach Something to the Stepper

If you want to mount an arm or pointer to the stepper motor, you need to make a hole for the pointer that fits the shaft perfectly. You could measure this with a caliper. There are also collars and shaft couplers that you can buy for various stepper motors that will allow you to attach things to your stepper. ServoCity has a number of examples, as does Pololu. To pick a good shaft adapter, you need to know what you’re going to do with the stepper, and what the size and shape of the shaft is.

Using an External Power Supply

Although the example shown above used a motor that can run on the voltage and current supplied to the Arduino via USB, this is not the norm for stepper motors. Most of the time you need to use an external power supply. You should match your supply to your motor. Keep in mind that if you have, say, a 12-Volt power supply and a 5-volt motor, you can add a 5-volt voltage regulator, as shown in the breadboard lab. Figures 17 through 19 show a few different options for powering different stepper motors.

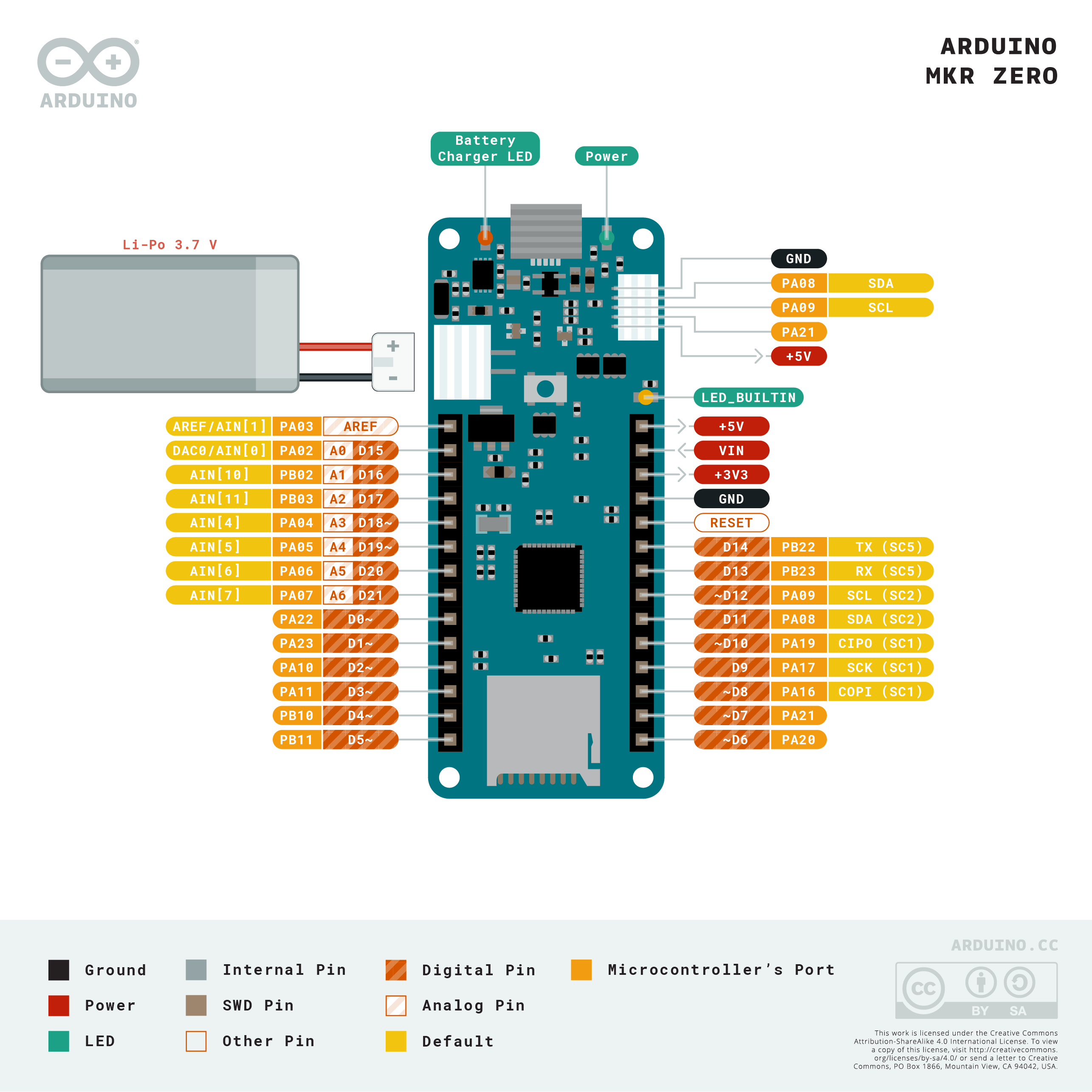

Figures 17 and 18 show how you might power a 9V stepper motor from an Uno or Nano, respectively. Figures 17 and 18 show a NEMA-17 stepper motor. Figure 19 shows how you could power a 5V stepper from a Nano, using a 9-12V DC power supply for the Nano and a 5V voltage regulator for the motor and motor driver.

The STSPIN220 can run motors from 1.8-10V. If you need to run a motor at a voltage greater than 10V, there are several other step and direction motor drivers that can do the job. For example, the A4988 is similar to the STSPI220, but has a motor voltage range of 8-35V. Many of them come with the same or similar pin arrangements as well. For a comparison, see the Step & Direction Drivers compared table in the Controlling Stepper Motors page of this site.

It’s worth noting that when the Nano 33 IoT is powered from its Vin pin, the USB connection no longer powers the Nano. Instead, the Vin powers the Nano. You can still get 3.3V from the 3.3V out pin (pin 2), however.

The exact voltage and amperage requirements for a stepper motor circuit will depend on the motor you are using. These images show a few options that can work, but you should adapt them depending on the particular electrical characteristics of your motor.

Advanced Features: Speed Control, Microstepping, and G-code

This lab has covered the basics of step & direction drivers. These drivers are capable of much more control, depending on how you wire them and how you program the microcontroller to control them.

Controlling the speed of a motor is managed by changing the timing between steps. You can manage this in your own code by changing the delay after each step pulse, or you can use a library like accelStepper which has options for speed control.

Microstepping allows you to control a stepper in 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, or as low as 1/256 step increments. The number of microsteps depends on the driver you are using. You set the microstep increment using the mode pins. Pololu’s documentation for the STSPIN220 covers the details of this for this board (see the section titled Step (and microstep) Size). Other step & direction boards will have similar instructions.

Step and direction motor controllers are often used in DNC machines like 3D printers and 3D mills. These machines have a communication format called G-code which describes how the machine should move to print or carve a shape. The GRBL library for Arduino translates G-code into a series of stepper motor movements. There are many sites which explain this in more depth, like the one at this link.

Applications

Stepper motors have lots of applications. One of the most common is to make a tw0- or three-axis gantry for CNC plotters, printers, and mills. A gantry is a structure on which you mount motors and the equipment that they are moving in order to achieve a task. Evil Mad Science’s AxiDraw is a good two-axis example. You can also use steppers to create animation in art projects, as seen in Nuntinee Tansrisakul’s Shadow through Time. Heidi Neilson’s Moon Arrow is another example that uses stepper motors and geolocation tools to make an arrow that always points at the moon.